Soaking it up

One of the most important organisms to the McMurdo Sound benthic (bottom-dwelling) community is the sea sponge. They are everywhere and amazing to see on every dive.

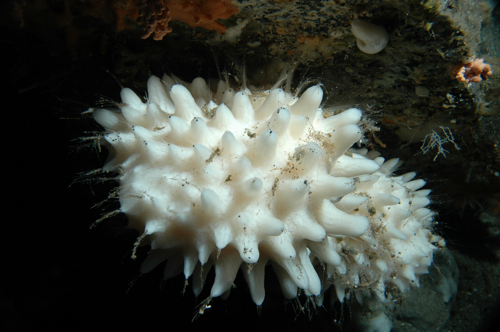

Sea sponges are found almost everywhere in McMurdo Sound. They are a very important part of the ecosystem. (Photo courtesy of Adam Marsh)

Sea sponges are found almost everywhere in McMurdo Sound. They are a very important part of the ecosystem. (Photo courtesy of Adam Marsh)

The Wonderful World of Sponges

Sponges come in a huge variety of shapes and sizes. It's really hard to talk about such a diverse group of organisms.

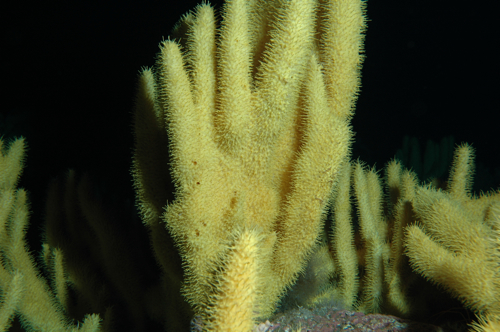

Some scientists believe that bright colors might be in response to ultraviolet light. (Photo courtesy of Adam Marsh)

Some scientists believe that bright colors might be in response to ultraviolet light. (Photo courtesy of Adam Marsh)

Sea sponges also come in a variety of shapes. (Photo courtesy of Adam Marsh)

Sea sponges also come in a variety of shapes. (Photo courtesy of Adam Marsh)

Sea sponges come in a variety of shapes, sizes, and colors. (Photo courtesy of Adam Marsh)

Sea sponges come in a variety of shapes, sizes, and colors. (Photo courtesy of Adam Marsh)

Classification

We organize organisms into different groups based on similarities and differences with other organisms. Here's how we classify (organize) the Volcano Sponge, Anoxycalyx (Scolymastra) joubini.

The Volcano Sponge, Anoxycalyx (Scolymastra) joubini. (Photo courtesy of Adam Marsh)

The Volcano Sponge, Anoxycalyx (Scolymastra) joubini. (Photo courtesy of Adam Marsh)

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Porifera

- Class: Hexactinellida

- Order: Lyssacinosida

- Family: Rosellidae

- Genus: Anoxycalyx (Scolymastra)

- Species: joubini

Adaptations

Sea sponges come in many interesting shapes and sizes, but a common one is the basket-shape. The sea sponge is tall and solid looking from the outside. In the center there is usually a large hollow space - sort of like a basket. When you look down into this hollow area, you see that there are hundreds, maybe even thousands of small holes with channels. Often, there are fibers crossing these holes. I bet you can figure out how the sponges use these holes and fibers.

Here's what the inside of a volcano sponge looks like. (Photo courtesy of Brenda Konar)

Here's what the inside of a volcano sponge looks like. (Photo courtesy of Brenda Konar)

Sea sponges are known as filter feeders. They are actively pumping water through their bodies. As the water passes through, they trap microscopic organisms floating within the water. This becomes the food source for the sponge.

What's really interesting is if you look at the parts of a sponge. Sea sponges don't have internal organs. That's right - there is no circulatory, muscular, or cardiovascular system. Instead, sea sponges are made up of four different cell types.

First, on the outside, there are epidermal cells. These form the outside structure of the sponge. Second, there are porocytes. These cells are like pores, or holes, that allow water to pass through the sponge. Third, there are collar cells, which have small hairs. These cells help move water through the sponge and those small holes. Finally, there are amoebocytes which perform several tasks. These include assisting in digestion, transport of nutrients, and building spicule (sea sponge skeletal fibers).

Sea sponges have dense skeletons. Some are even made of silica, and these are known as glass sponges. These skeletal fibers, called spicule are created and sometimes used to form a carpet around the sponge. It is believed that this carpet might keep out unwanted animals. Some species of sponge are also known to trap crustaceans. These carnivorous sponges have spicules with hooks, sort of like Velcro, for trapping their prey.

Some species of nudibranch prey upon sponges. (Photo courtesy of Adam Marsh)

Some species of nudibranch prey upon sponges. (Photo courtesy of Adam Marsh)

Sea sponges also use chemicals to help them compete in the environment. At least two sea sponges, Isodictya erinacea and Anoxycalyx (Scolymastra) joubini, are known to produce a chemical that has antibacterial, antimicrobial, and anti-yeast properties.

The sea sponge, Isodictya erinacea. (Photo courtesy of Adam Marsh)

The sea sponge, Isodictya erinacea. (Photo courtesy of Adam Marsh)

Interesting Observations

- A chemical from Anoxycalyx (Scolymastra) joubini has antibacterial, anti-fungal, and anti-yeast activity. This could be useful in the field of medicine.

- Anoxycalyx (Scolymastra) joubini appears to be slow growing, although just how slow growing seems to be debatable.

- Some sponges are though to live to be very old, like hundreds of years old. Again, exactly how old in the subject of some debate.

- Sea sponges are thought to have been on our planet for the last 580 million years.