Welcome to the Virtual Base Camp, the starting point for your exploration of the polar regions with PolarTREC teachers and researchers!

2012 Expedition Timeline

Expeditions

Winter Sampling

What Are They Doing?

Carin describing where they are sampling.

Carin describing where they are sampling.

During this cruise, the team collected some of the first winter information ever collected on the biology, chemistry, and physical oceanography of the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas. In particular, they studied a very small crustacean called a copepod. Copepods make up the base of the ocean food chain. In addition to studying the ecology, scientists on board were looking at chlorophyll, marine mammals, and birds. Data collected during the cruise was used to predict future impacts of climate change on the oceans.

Expedition Map

Weddell Seals in the Ross Sea

What Are They Doing?

Weddell seal pup (Photo by Michael League)

Weddell seal pup (Photo by Michael League)

Weddell seals live in the region surrounding Antarctica, and spend their time on sea ice and in the water. They get most of their food from the sea, eating fish, krill, squid, and crustaceans. They are able to stay underwater for about 80 minutes while they look for food, and are known for making very deep dives of up to 700 meters (2300 feet).

The research team was interested in learning more about Weddell seals by studying how they dive and forage for food during the winter, when days are shorter and there is more sea ice cover. They were also interested in collecting oceanographic data, such as water temperature and salinity.

The research team collected this information by traveling to places where Weddell seals were hauled out on the sea ice, and briefly capturing them. Once they captured a seal, they conducted an exam in order to determine its health and condition. The researchers also put a satellite-linked dive recorder on each seal that they captured. These devices transmit data showing where, how often, and how deep the seals are diving. In addition, the devices record the temperature and salinity of the water where seals are diving.

Currently there is not a lot of information about how Weddell seals find food during the winter. Without this information, it is difficult to predict how seals will respond to changing environmental conditions. By using the seals to collect ocean data, the team has collected important information which is used to develop models to predict the role of the Southern Ocean in global climate processes.

Seafloor Organisms and Changing Ocean Conditions in Antarctic

What Are They Doing?

Underwater World

Underwater World

This project studied the effects of rising ocean acidification and temperatures on seafloor dwelling animals in the shallow waters of Antarctica. Carbon moves around the earth, between land, atmosphere, and water in the carbon cycle. The ocean absorbs Carbon Dioxide (CO2) from the Earth’s atmosphere. As increasing amounts of Carbon Dioxide are absorbed, the pH of the water is decreasing or becoming more acidic. This is called ocean acidification.

Several marine animals, such as mussels, snails, sea urchins, and more use the naturally occurring calcium (Ca) and carbonate (CO3) in seawater to construct their shells or skeletons. As seawater becomes more acidic, carbonate becomes less available, which makes it more difficult for these organisms to form their skeletal material. This negatively affects the health of the animal in many different ways.

In Antarctica, it is predicted that water temperatures will increase and the calcium carbonate needed by these organisms will decrease. Being sensitive to small changes in water temperatures and unable to form adequate shells and skeletons, many of these animals may have declined in health. Understanding how these small animals will react to changing ocean conditions is important, as several larger animals rely on them as a food source.

To collect their data, SCUBA divers dived to the seafloor and collected organisms. The research team ran several experiments on the animals to see how they would respond to changes in water acidification and temperature.

Impacts of the Larsen Ice Shelf System on the Weddell Sea

What Are They Doing?

Trawling for organisms off the Antarctic peninsula

Trawling for organisms off the Antarctic peninsula

This project was an international, interdisciplinary effort to address the rapid environmental changes occurring in the Antarctic Peninsula region as a consequence of the abrupt collapse of the Larsen B Ice Shelf in the fall of 2002. As a result of this collapse, a profound transformation in ecosystem structure and function has been seen in the coastal waters of the western Weddell Sea. This transformation appears to be redistributing the flow of energy between organisms, and to be causing a rapid change in the ecosystem beneath the ice shelf. For instance, the previously dark waters of the Larsen B embayment now support a thriving phototrophic community, with production rates and phytoplankton composition similar to other productive areas of the Weddell Sea.

The overarching goal of the LARISSA (LARsen Ice Shelf System, Antarctica) project was to describe and understand the basic physical, geological, and biological processes active in the Larsen embayment that contributed to the present phase of massive, rapid environmental change. Dr. Vernet's research group worked to determine abundance, diversity, and production of marine phytoplankton in the Larsen B region. The team used shipboard samplers and moored sediment traps to sample from the water column up to depths of approximately 600 m. They did this to determine how much production is supported in the region, its distribution in space and time, and how the organic matter transfers into higher trophic levels and reaches the sediments. Time onboard the ship was spent selecting sampling locations, collecting water, filtering samples for analysis, and analyzing samples on board. They also collected water to isolate diatom species and brought them back to the lab for further experimentation. Results from this research allowed scientists to predict the likely consequences on marine ecosystems of ice-shelf collapse in other regions of Antarctica vulnerable to climate change.

Expedition Map

Airborne Survey of Polar Ice

What Are They Doing?

The cockpit of a NASA aircraft

The cockpit of a NASA aircraft

IceBridge, a six-year NASA mission, is the largest airborne survey of Earth's polar ice ever conducted. The research team experienced first-hand the excitement of flying a large research aircraft over the Greenland Ice Sheet. While in the air they recorded data on the thickness, depth, and movement of ice features, resulting in an unprecedented three-dimensional view of Arctic ice sheets, ice shelves, and sea ice.

Operation IceBridge began in 2009 to bridge the gap in data collection after NASA's ICESat-1 satellite stopped functioning and when the ICESat-2 satellite becomes operational in 2016, making IceBridge critical for ensuring a continuous series of observations in the Arctic. IceBridge flies over these regions to map Arctic areas once a year. By comparing the year-to-year readings of ice thickness and movement both on land and on the sea, scientists can take a yearly look at the behavior of the rapidly changing features of the Greenland ice and learn more about the trends that could affect sea-level rise and climate change around the globe.

Expedition Map

Nutrient Transport in Arctic Watersheds

What Are They Doing?

Stream flowing through arctic tundra

Stream flowing through arctic tundra

The research team evaluated how changes in water and nutrient cycles on land can affect stream networks in the Arctic. Changing climate in the Arctic may contribute to increases in the transport of nutrients to river networks and oceans by causing the release of nutrients from thawing permafrost, altering precipitation patterns, increasing rates of biogeochemical reactions, or expanding storage capacity in thawed soils. These changes may have far-reaching effects because flowing water connects land to downstream aquatic ecosystems.

Since the flowpaths connecting terrestrial ecosystems to stream networks remain poorly understood, the group focused on transport and reaction of water and solutes within water tracks, which are linear regions of surface and subsurface flow that connect hillslopes to streams and account for up to 35% of watershed area in arctic tundra. The research increased our understanding of the role of hillslopes in connecting terrestrial ecosystems to stream networks.

Expedition Map

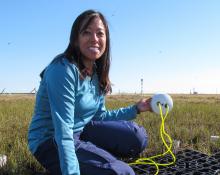

Tundra Nutrient Seasonality

What Are They Doing?

Tundra plants and antler

Tundra plants and antler

Arctic soils have large stores of carbon and as the arctic environment warms, this carbon may be released to the atmosphere in the form of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane. The current understanding of tundra ecosystems and their responses to climate change is based on the idea that nitrogen limits plant growth, however nitrogen availability is strongly seasonal, with large amounts available early in the growing season but very little available later on.

Since nutrient cycling on the tundra changes throughout the season, the research team worked to understand how seasonal changes in tundra plants and soil dynamics are affected by changes in the timing of snowmelt and warming. By experimentally manipulating factors such as the timing of spring thaw and fall freeze directly on the tundra, the team could study how this affects the ecosystem directly. The team was engaged in a mixture of outdoor field sampling, experimentation, and laboratory work. Through this research, the team aimed to better predict the impacts of changing growing season timing and duration on the carbon balance of arctic ecosystems.

Expedition Map

Predatory Spiders in the Arctic Food Web

What Are They Doing?

Wolf Spider

Wolf Spider

While arctic species are all well adapted to living in extreme environments, it is unclear whether different species will respond similarly or differently to the environmental shifts that accompany climate change (e.g. longer growing seasons and warmer temperatures). Stronger responses by some species within a community, or strong responses by certain species groups, could lead to changes in the structure of the food web and its role in arctic ecosystems.

For example, In the Alaskan Arctic, wolf spiders are the largest and most abundant invertebrate predators. A shift in their ecological role could therefore have an important impact on the entire food web. Evidence from Arctic Greenland shows that wolf spider body sizes are becoming larger in response to longer growing seasons. These increases in body size will likely lead to larger spider populations, which could imply an increase in predation on the rest of the community.

This project explored the role of wolf spiders within arctic communities and specifically, whether climate change is stimulating changes in these predators that could influence the structure and functions of arctic food webs. The research team used a variety of methods to examine the impact of wolf spiders, including sampling spiders from various locations around Toolik Lake and carrying out a manipulative experiment that looked at the entire food web.

Expedition Map

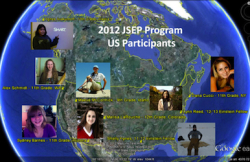

Greenland Education Tour 2012

What Are They Doing?

Glacier outside of Kangerlussuaq, Greenland

Glacier outside of Kangerlussuaq, Greenland

The expedition members visited several research sites in Greenland as part of an initiative to foster enhanced international scientific cooperation between the countries of the United States, Denmark, and Greenland. The expedition members spent several days learning about the research conducted in Greenland, the logistics involved in supporting the research and gained first-hand experience conducting experiments and developing inquiry-based educational activities.

The 2012 expedition's work built on past expeditions and was supported by the National Science Foundation. The project was developed through cooperation with the U.S.-Denmark-Greenland Joint Committee, which was established in 2004 to broaden and deepen cooperation among the United States, the Kingdom of Denmark, and Greenland.

JSEP Participants from the United States

JSEP Participants from the United States

The program had two components.

Kangerlussuaq Science Field School: 29 June - 12 July 2012

US Science Education Week: 12- 22 July 2012

Expedition Map

Siberian Arctic Systems Study

What Are They Doing?

Sampling river water

Sampling river water

The Polaris Project is an innovative international collaboration among students, teachers, and scientists. Funded by the National Science Foundation since 2008, the Polaris Project trains future leaders in arctic research and informs the public about the Arctic and global climate change. During the annual month-long field expedition to the Siberian Arctic, undergraduate students conduct cutting-edge investigations that advance scientific understanding of the changing Arctic. During the Polaris Project field course, students and faculty work together to study the Arctic as a system. Instead of focusing on a single question in a single ecosystem type, the group considers a range of questions across multiple components of the Arctic System including forests, tundra, lakes, rivers, estuaries, and the coastal Arctic Ocean. The unifying scientific theme is the transport and transformations of carbon and nutrients as they move with water from terrestrial uplands to the Arctic Ocean. They emphasize the linkages among the different ecosystems, and how processes occurring in one component influence the others.

Expedition Map

Microbial Activity in Thawing Arctic Permafrost 2012

What Are They Doing?

Caribou skull on the tundra

Caribou skull on the tundra

Underlying the northern arctic coast of Alaska is a thick layer of permafrost. As water melts and pools on top of the permafrost, thaw lakes are formed. Much of the North Slope of Alaska is covered in such thaw lakes. As they decompose organic material, the bacteria and other microorganisms living in thaw lakes produce either carbon dioxide or methane, depending on the conditions. Methane is a highly potent greenhouse gas with a global warming potential 22 times that of carbon dioxide, and increased microbial activity in thawing permafrost areas could lead to changes in the atmosphere due to the increased release of methane. This research was important to better understand the factors controlling competing microbial processes in carbon-rich tundra soils and how microbial activities interact with biogeochemical cycles (the way specific chemicals move through living and non-living processes on Earth). This information was used to help understand the impacts that changes in climate have on tundra soils.

To collect their data, the research team combined research methods from biology, ecology, and biotechnology. In 2012, the team performed experiments to determine the role that bacterial processes play in the production of carbon dioxide, methane, and other gases from peat soils. They collected data in the field including gas flux measurements, soil cores, thaw depth, water table depth, pH, and dissolved oxygen content. Additionally, they monitored bacterial respiration and conducted related lab experiments.

Expedition Map

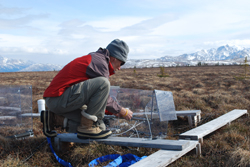

Carbon Balance in Warming and Drying Tundra 2012

What Are They Doing?

Setting up tundra experiments

Setting up tundra experiments

The carbon cycle is the means by which carbon is moved between the world’s soils, oceans, atmosphere, and living organisms. Northern tundra ecosystems play a key role in the carbon cycle because the cold, moist, and frozen soils trap rotting organic material in the soils. This very slowly decaying organic material has caused carbon to build up in the Arctic during the past thousands of years. Now warming in the Arctic is slowly causing the tundra to become warmer and dryer. As a result, the trapped carbon leaves the soil as carbon dioxide and goes into the atmosphere.

The research team studied changes to the carbon cycle in northern forests by setting up experiments that simulate a warmer and dryer tundra. When they arrived at the field site they first removed snow from the research sites and then set up an automated carbon dioxide measurement system and warming chambers. After the set-up, the team took field measurements of carbon dioxide exchange between the soil and atmosphere, permafrost thaw depth, and water table depth. In addition, they took plant and soil samples and studied the timing of plant life events, also known as phenology. In 2012, the team also took methane and radiocarbon measurements.

The experiment was part of the Carbon in Permafrost Experimental Heating Research (CiPEHR) project. The results of their research will help in predicting how the warming and drying tundra will affect the carbon balance, and how the release of additional carbon dioxide will affect global climate change.

Expedition Map

Early Human Settlement in Arctic Alaska 2012

What Are They Doing?

A sample of chert unearthed at Raven Bluff, Alaska

A sample of chert unearthed at Raven Bluff, Alaska

The team excavated portions of the Raven Bluff archaeological site, the remains of a prehistoric camp that date to the very end of the last ice age, about 10,000 years ago. The site in Northwestern Alaska is important because it contains the oldest well-preserved collection of archaeological animal bone in the American Arctic. The goal of this research was to gather information at the site that can teach us about what the people who occupied the Raven Bluff site ate; how they obtained, processed and stored their food; and how they manufactured their tools, clothing, and housing.

The site also contains fluted projectile points – a type of stone spear tip that is associated with many of the earliest archaeological sites in the continental United States. Fluted projectile points have been found throughout the Americas, but have never been reliably dated in Alaska. Because people migrated from north-to-south after entering the Americas from Asia across the Bering Land Bridge, fluted points in the far north are expected to be older than the fluted projectile points found in the continental United States. However, initial findings from Raven Bluff indicate that the fluted projectile points at this site are actually younger than the oldest fluted projectile points in the continental United States. By dating these artifacts, the research team is studying the nature and timing of early human population movements in the Americas.

In addition to providing information on early human settlement patterns, the animal remains from this site may shed light on the long term history of caribou populations in what is now the home of the western arctic caribou herd, a resource of critical importance to local residents and a key issue of concern for biologists and wildlife managers.

Expedition Map

High Arctic Change 2012

What Are They Doing?

Taking an ice core of a glacier on Svalbard

Taking an ice core of a glacier on Svalbard

The research team of undergraduate geoscience students that participated in the Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) Program traveled to Svalbard to conduct independent research projects. The research focused on how climate influences the modern glacial, river, and lake systems in order to better interpret the sediment record of past climate change.

The team investigated how high latitude glaciers, melt-water streams, and sedimentation in lakes and fjords respond to changing climate conditions. The Svalbard region has been marked by the retreat of glaciers, reductions in sea ice, and measurable warming during the past 12,000 years, and more specifically during the last 90 years. Svalbard's high latitude location, its location at the end of the Gulf Stream, combined with its relatively easy access, makes it an ideal location for this study. Svalbard has an arctic climate and is home to many large glaciers, including alpine glaciers in the mountains, and tidewater glaciers that end in long narrow bodies of seawater called fjords. The region is ideal for the study of past climate because the Arctic is highly sensitive to changes in climate and several different types of measurements on and around glaciers can be conducted there.

Expedition Map

Ecosystem Study of the Chukchi Shoal

What Are They Doing?

Raising a Conductivity, Temperature, and Depth (CTD) sensor

Raising a Conductivity, Temperature, and Depth (CTD) sensor

The northern Chukchi Shelf receives large inputs of organic matter from the highly productive shelf regions of the North Pacific and from local sources of primary production, including algae in the ice and sediment and phytoplankton in the water column. As a result, highly productive biological "hotspots" have been documented in the vicinity of Hanna Shoal. Because of the biological significance of this region and its importance for oil and gas exploration and development, the team planned a multi-disciplinary investigation to examine the biological, chemical, and physical properties that define this ecosystem.

Previous work in the area has profiled the biogeochemistry of the northern Chuckhi Sea, but this study focused more particularly on the Hanna Shoal region, looking at phytoplankton and zooplankton in the open ocean as well as the physical oceanography through direct measurement of circulation, density fields, and ice conditions.

Expedition Map

Oceanographic Conditions of Bowhead Whale Habitat

What Are They Doing?

Bowhead whale jawbones on the beach in Barrow, Alaska

Bowhead whale jawbones on the beach in Barrow, Alaska

The research team worked out of Barrow, Alaska at the juxtaposition of two Arctic seas; the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas. It is a region frequently traveled by the endangered bowhead whale. This project had its genesis in understanding why the region near Barrow, Alaska is a feeding hotspot for migrating bowhead whales. The whales and their prey will continue to be a focus of the team's interpretations. The research team conducted oceanographic sampling of the physical and biological marine environment in the region over the period 2005-2011 and observed significant inter-annual variability. Long-term studies of the ocean conditions in the Arctic are needed in order to understand how these environments vary inter-annually. The research team will continue to document conditions in the biological-physical ocean ecosystem, through annual boat-based surveys, in order to predict and understand the potential impacts of climate change on the Arctic ecosystem.

¿Quienes son?

Titulo financiado: Observación anual del medio ambiente marino biológico y físico en los mares Chukchi y Beauford en las cercanías de Barrow, AK.

El equipo de investigación viajará por avión a Barrow, una comunidad pequeña de aproximadamente 4,500 habitantes en la costa norte de Alaska. Como permitan las condiciones del tiempo, el equipo se embarcara para la colección de muestras oceanográficas a bordo del buque de investigación Annika Marie de 43 pies. Las actividades de a bordo incluirán colección de agua y plancton y mediciones de conductividad, temperatura, y profundidad. A bordo también tomarán nota sobre las ocurrencias de mamíferos marinos y realizarán el procesamiento preliminar de muestras. Si el clima es malo para navegar en el océano ellos pasarán el tiempo en Barrow catalogando muestras y organizándose para los días que pasaran sobre el agua.

Expedition Map

Russian American Long term Census of the Arctic

What Are They Doing?

Scientists sampling in the Chukchi Sea

Scientists sampling in the Chukchi Sea

The Russian-American Long-term Census of the Arctic (RUSALCA) is a joint NOAA/Russian Academy of Sciences sponsored program whose mission is to document the long-term ecosystem health of the Pacific Arctic Ecosystem. Research cruises through the Bering Strait and Chukchi Sea in both U.S. and Russian waters provide the ability for sampling irrespective of political or exclusive economic zone boundaries.

These seas and the life within them are biologically rich and are thought to be particularly sensitive to global climate change because they are in areas where steep thermohaline and nutrient gradients in the ocean coincide with steep thermal gradients in the atmosphere. The Bering Strait acts as the only Pacific gateway into and out of the Arctic Ocean and as such is critical for the flux of heat between the Arctic and the rest of the world. One of the overall goals of the entire project was to monitor the flux of fresh and salt water in the region and to establish benchmark information about the distribution and migration patterns of the biologically rich life in these seas. Dr. Grebmeier's research on this final cruise of the project was particularly focused on benthic biological communities and their associated sediment chemistry.

Tectonic History of the Transantarctic Mountains

What Are They Doing?

Seismic station on the ice

Seismic station on the ice

Antarctica plays a central role in global tectonic evolution. Competing theories have been put forward to explain the formation of the Transantarctic Mountains (TAMs) and the Wilkes Subglacial Basin (WSB), primarily due to a lack of information on the crustal thickness and seismic velocity of the areas. The research team attempts to resolve how the TAMs and WSB originated and how their formation relates to Antarctica’s geologic history. Since most of Antarctica is covered by large ice sheets, direct geologic observations cannot be made; therefore, “remote sensing” methods like seismology must be used to determine details about the earth structure.

The goal of this project, funded by the National Science Foundation, was to broaden our knowledge of geology in this region with a new seismic project; the Transantarctic Mountains Northern Network (TAMNNET), a 15-station array across the northern TAMs and the WSB that will fill a major gap in seismic coverage. Data from TAMNNET was combined with that from previous and ongoing seismic initiatives and was analyzed to generate an image of the seismic structure beneath the TAMs and the WSB.

While in the field, the team spent most of their time deploying seismic stations that compose the new TAMNNET array. This included loading equipment onto small airplanes, flying to remote field locations, digging large holes in the snow/ice to shelter the equipment, and assembling and testing the seismic hardware.

Expedition Map

Space Weather Monitoring on the Antarctic Plateau 2013

What Are They Doing?

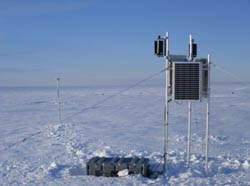

Automatic Geophysical Observatories (AGOs)

Automatic Geophysical Observatories (AGOs)

The purpose of the project was to monitor "space weather." Space weather encompasses phenomena that take place a few hundred miles above the surface of the Earth. This includes the ionosphere, the magnetic fields of the Earth and Sun, the northern and southern lights, and the solar wind. A high-latitude location (either north or south polar regions) is ideal for such monitoring because in these regions the field lines of the Earth's magnetic field become almost perpendicular to the Earth.

To do this, scientists created Automatic Geophysical Observatories (AGOs) that are active at five locations established across the Antarctic Plateau that house nearly identical instruments measuring atmospheric weather conditions. During their stay, the team made sure all of the different instruments were working properly and collecting reliable data. Supporting these observatories is crucial to the study of interactions between the magnetic fields of the Sun and of the Earth. Learning more can help us understand the potential disturbances in these fields that can disrupt radio communications or our power systems, and even take out satellites that orbit close to Earth.

Buried Ice in Antarctica 2012

What Are They Doing?

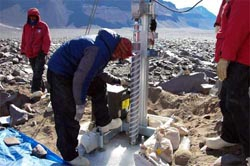

Setting up a drill site in the Dry Valleys, Antarctica

Setting up a drill site in the Dry Valleys, Antarctica

A small team of earth scientists and engineers used a specialized drill to reach buried ice deposits in the Dry Valleys region of Antarctica. Stagnant and/or slow-moving debris-covered glaciers may contain ice several million years in age. By comparison, the oldest ice yet cored from the East Antarctic Ice Sheet is approximately 1 million years old. As a result, these buried ice deposits hold an ancient archive of Earth's past atmospheric conditions. Each ice core enabled the research team to gain access to a reliable record of atmospheric and climatic change extending back for many millions of years, making it by far the oldest ice yet known on this planet.

In addition to drilling for ancient ice, the team worked in the Dry Valleys to seek a better understanding of surface processes that play a critical role in maintaining and/or modifying buried glacier ice. Despite their age and potential to register long-term climate change, there has been surprisingly little research on the geologic and geomorphologic processes that both preserve and modify debris-covered glaciers in Antarctica. In addition, the cold polar desert of the Dry Valleys is one of the most Mars-like climatic environments and landscapes on Earth, serving as a proxy for very ancient ice buried on Mars and providing insight into Martian history and the potential for life on Mars.

Expedition Map

IceCube In Ice Antarctic Telescope 2012

What Are They Doing?

The building that houses the IceCube project

The building that houses the IceCube project

A large international team of scientists and drilling technicians worked throughout the austral summer to continue testing with the world's largest scientific instrument, the in-ice IceCube Neutrino Detector. Neutrinos are incredibly common (about 10 million pass through your body as you read this) subatomic particles that have no electric charge and almost no mass. They are created by radioactive decay and nuclear reactions, such as those on the Sun and other stars. Neutrinos rarely react with other particles or forces; in fact, most of them pass through objects (like the earth) without any interaction. This makes them ideal for carrying information from distant parts of the universe, but it also makes them very hard to detect. All neutrino detectors rely on observing the extremely rare instances when a neutrino does collide with a proton. This collision transforms the neutrino into a muon, a charged particle that can travel for 5-10 miles and generate detectable light.

IceCube is located in Antarctica because the huge amount of dense ice under the South Pole contains many protons that can be hit by passing neutrinos, and the ice is transparent, so the resulting light can be detected by sensors. IceCube is made up of 4200 sensitive light detectors embedded in the ice at depths between 1450 and 2450 meters (4700-8000 feet). The sensors are deployed on "strings" of 60 modules each, into holes 60 cm in diameter in the ice melted using a hot-water drill. Encompassing a cubic kilometer of ice, IceCube expands on an existing experiment that started detecting neutrinos at the South Pole in 1997. When IceCube is complete, it may detect up to 300,000 neutrinos a year for up to 20 years.

The data collected will be used to make a "neutrino map" of the universe and to learn more about astronomical phenomena, like gamma-ray bursts, black holes, exploding stars, and other aspects of nuclear and particle physics. However, the true potential of IceCube is discovery; the opening of each new astronomical window has led to unexpected discoveries.