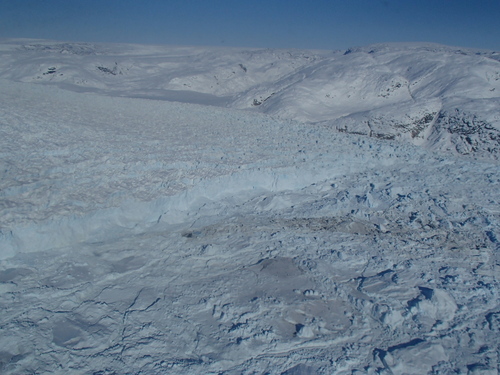

The ice cliff running from lower left toward upper right is called the calving front.

The ice cliff running from lower left toward upper right is called the calving front.

Two glacial valleys merging.

Two glacial valleys merging.

Today was my first flight aboard NASA's P-3B Orion airborne science lab. Even though I promised, and very much want to, write about all the really cutting edge, nerdy science that these brilliant people are doing ... today's journal is simply about the emotion and beauty of the day.

Words are not enough to describe the rugged beauty.

Words are not enough to describe the rugged beauty.

My daughter once asked me why I used a particular "big" word when there was a perfectly good "small" word. I told her it was important to have a good vocabulary, but never explained to her why. I understand today why. And I found my meager vocabulary wholly lacking. Amazing, awesome, beautiful, stark, breathtaking, and stunning failed with in the first minute of reaching Eastern Greenland's fjords.

Grease ice named for its greasy appearance.

Grease ice named for its greasy appearance.

Flying at 1,500 feet below the tops of mountains, through valleys so narrow I felt I could reach out and touch the sides was … simply astonishing. I took hundreds of pictures and lots of video, and looking at it now … it’s just not the same.

Iceberg - about 50 meters tall.

Iceberg - about 50 meters tall.

When compressed into two dimensions ... it lacks the emotional content and majesty it had in real life. I’ve posted some of those pictures and a short video clip to try to communicate the beauty, vastness, and splendor of this piece of the world. If they fail to do so for you, it is solely the shortcomings of the photographer and the flatness of digital media. It was truly incredible.

The variety of colors was surprising.

The variety of colors was surprising.

I was surprised by the variety of color; brown rocks in shades of mocha, caramel, and chocolate, the black shadows rendered in grey, blue ice in varieties of aquamarine and cerulean, the azure sky, and of course the white snow, miles upon endless miles of unbroken white snow across the vast stretches of the interior. I had expected a monochromatic world and I was happily disappointed.

Greenland has thousands of islands. So many are covered by ice that no one knows the exact count.

Greenland has thousands of islands. So many are covered by ice that no one knows the exact count.

I didn't know what to expect, emotionally, from flying in a relatively small aircraft, low to the ground, through remote places on the planet (if radio contact is lost for more than 30 minutes, they send out the search and rescue team). I tried not to panic during the safety video and somehow kept from hyperventilating during the aircraft walk-through when flight engineer Mike said, "But we're not going out that hatch unless something real bad happens, like we put down in the water."

The cliffs on the calving front are 80 meters or 250 feet tall.

The cliffs on the calving front are 80 meters or 250 feet tall.

I got the feeling he substituted "put down" for "crash" when he looked into my dilated pupils. He showed me where the axe is kept for some sort of contingency. I quickly forgot what he said as my primitive brain was scrambling to decide whether to fight or take flight.

Frighteningly beautiful.

Frighteningly beautiful.

Strapping into the claustrophobic four-point harness in the jump seat, directly behind the pilot, I was prepared for complete inner chaos. I didn’t want to panic in front of the pilots, they’re ex-Navy now flying for NASA – not exactly pilot-school drop-outs. I slipped on a pair of noise canceling headphones (a 4-engine P-3 is noisy) and tuned into the cockpit preflight check and I was suddenly, startlingly … calm.

Just incredible landscapes.

Just incredible landscapes.

It may have been their professionalism, it may have been their banter (like you and your good friend at work might have), it may have been the incredible view looking straight up the Watson River valley out the windshield, or it may have been divine providence. Regardless, I was grateful. From that moment on I was at peace. Even through a spot of rough air that one veteran rated a 7 out 10 (reeeally not looking forward to a 10), I absorbed the astonishing experience in tranquility.

We had just flown up this glacial valley.

We had just flown up this glacial valley.

At times the scenery was beautiful enough to bring me to tears, I mean, if I was the crying type. I am decidedly not, just to be clear. Even the veterans (for one, this is his 23rd trip to Greenland) were running to the windows to shot photos, and the pilots were taking pictures or turning on their dash mounted GoPro cameras.

Even the veterans of many flights were taking lots of pictures.

Even the veterans of many flights were taking lots of pictures.

This part of eastern Greenland is incredibly rugged, remote, and unique. The area near the shore is carved everywhere by glaciers, pouring down to the sea off the vast interior dome of ice. The term glacial, in the gradual sense, does not apply here. From low altitude you can see how the glaciers move. You can see streamlines, like smoke in a wind tunnel. You can see eddies as the glaciers move around obstacles. You can see how friction with the valley sides causes the glacier to slow and sheer. The glaciers and not glacial at all … they are dynamic.

Amazing to see the glacial streamlines in the ice.

Amazing to see the glacial streamlines in the ice.

Coupled with the scenery was the incredible flying. In order to get data on glaciers, the pilots have to fly along the glacier – and only 1,500 feet above it as it winds up or down the valley My son plays War Thunder, a WWII video game on the PC. In that game you fly WWII aircraft through valleys, banking and climbing and diving. Today, I lived that game.

I spent about 3 hours here taking pictures.

I spent about 3 hours here taking pictures.

If you don’t play War Thunder, then maybe you’ve seen IMAX movies where the plane flies in between two peaks, seemingly just feet off the ground. Then the ground drops suddenly away, your stomach sinks, and suddenly you're a thousand feet in the air. I lived that today.

We fly below the mountains through the glacial valleys.

We fly below the mountains through the glacial valleys.

I’ve struggled throughout this journal to find the right words. Maybe you can think of the best Ansel Adams photograph coupled with Robert Frost’s best poetry and seasoned with Henry Thoreau – that one person could probably bring you the experience I had today. I understand why science writing is a career. My linear and logical brain was at a loss much of the day.

Open leads in the ice.

Open leads in the ice.

My one non-emotional message today is to students: Study science and engineering! The plane was full of those types today. I can think of no other career that affords you the kind of experience of waking up in the morning, climbing into an airplane, turning on millions of dollars-worth of equipment, flying over some of the most beautiful scenery on earth, collecting data that can have a meaningful impact, and going to bed knowing you get to see more awe-inspiring stuff tomorrow. Engineers and scientists have the coolest jobs on the planet. Pun intended.

The icebergs on the right are 'dirty' because when they calved, they tipped over, exposing their bottom surfaces.

The icebergs on the right are 'dirty' because when they calved, they tipped over, exposing their bottom surfaces.

This iceberg is about 100 meters tall.

This iceberg is about 100 meters tall.

Sea Ice.

Sea Ice.

Yes, another glacier!

Yes, another glacier!

A nunatak is just the top of a mountain sticking out of the ice.

A nunatak is just the top of a mountain sticking out of the ice.

http://

Note the hanging glacier in the middle of the ridge.

Note the hanging glacier in the middle of the ridge.

Question

All the science equipment uses a lot of electricity. The electricity is divided into three subsystems or parts so no one part has to supply all the electricity itself. That was if one part stops working, there are still two other parts that can continue working.

The amount of electricity that flows is called ‘current’ and is measured in amperes or amps.

Age 0-9: The three parts of the electrical system supply 19, 25, and 17 amps. Add those numbers together to find the total amount of electricity that is flowing?

Age 10-13: Divide the voltage, 120, by the total amount of electricity flowing (from the first question) to find the effective resistance. Resistance is measured in ohms.

Age 11+: What is the total power consumed by the science gear on the plane? (Power = Voltage x Current)

Answers

Answer in the Ask the Team section. State your name and age (11+ is fine if you are embarrassed by your age). This should be obvious, but you are only eligible for a prize in your own age category or higher … Mike!