John Sonntag is the choreographer of NASA’s Operation IceBridge. As a high schooler in Texas he saw the Omnimax movie The Dream is Alive about NASA’s space program, and he knew then that he wanted to be a part of it.

John Sonntag on the left with Robert Harpold in their navigation seats.

John Sonntag on the left with Robert Harpold in their navigation seats.

John is involved in just about every facet of the project, from mission planning to in-flight navigation, from meteorology to data analysis, and from calibration of equipment to worrying about getting the science team all the data they want. He’s also the founding member of the OIB Running Club! There’s no official club, really, but John is a life-long runner and I was happy to find a fellow runner, especially one who was about my age and speed.

The unofficial OIB Running Club. John Sonntag, Bruno Camps-Raga, and I on a run in Kangerlussuaq.

The unofficial OIB Running Club. John Sonntag, Bruno Camps-Raga, and I on a run in Kangerlussuaq.

The campaign this year in Greenland actually started about a year ago; as soon as last year’s campaign was over. A science team, comprised of 12-15, mostly of university researchers, meets to review past data and set priorities as to where more data is needed. The science team lists high, medium, and low priority targets.

John plots the the day's mission.

John plots the the day's mission.

Part of John’s job is to take the goals of that science team and develop mission plans, or daily flights, that will accomplish as many of the goals as possible. From more than 20 years’ experience in polar science, John often finds ways to accomplish multiple goals in a single mission. To do that he factors in aircraft performance, weather, geography, and about a dozen other things. It’s a complex dance to choreograph.

Michael Studinger and John check the weather with the local meteorologist.

Michael Studinger and John check the weather with the local meteorologist.

For this years’ Greenland campaign John had 54 missions planned for a potential of around 30 days of flying. John said, ‘You always want options. The weather might be bad in the north so you need options in the south.’ With time remaining, the team thinks they can get about 26 missions flown. A remarkable accomplishment when you account for bad weather, aircraft maintenance, and mandatory crew rest – you really don’t want over-tired pilots or flight engineers! While I was with them they finished all of the high priority missions out of Kangerlussuaq. It was obvious that every team member was proud to have done this. When the P-3 departed Kangerlussuaq for the last time to head to Thule Air Base in the north for the final two weeks of the campaign, they had even planned a short mission along the way to collect some data. They just never stop doing science.

There can be a lot of pressure to pick the right mission in terms of weather, so John spends a great deal of time studying it.

There can be a lot of pressure to pick the right mission in terms of weather, so John spends a great deal of time studying it.

During missions John is the principal navigator along with Robert Harpold. Together they wrote all of the computer code that helps the pilots fly the exact same paths year after year. It’s critical to studying data over any period of time to get data from, literally, the same spot on the ground every year. Without going into too much technical detail, the computer code ‘fakes’ Instrument Landing System (ILS) signals. ILS is the system planes use to land when they can’t actually see the runway due to fog, clouds, or light conditions. The most modern planes can ‘land themselves’ using ILS. The code doesn’t try to land the land, but it’s used to keep the plane flying right along the correct route, even if that route twists and turns through glacial valleys.

John, Michael, and pilot Scott Farley go over the day's mission in the weather office.

John, Michael, and pilot Scott Farley go over the day's mission in the weather office.

One other critical mission for John and IceBridge is to verify satellite data. Some of the missions involve flying long straight segments. These are past or current satellite tracks. Operation IceBridge is pivotal for calibrating data from past missions like IceSat I, current missions like the ESA's CryoSat, and future missions like IceSat II.

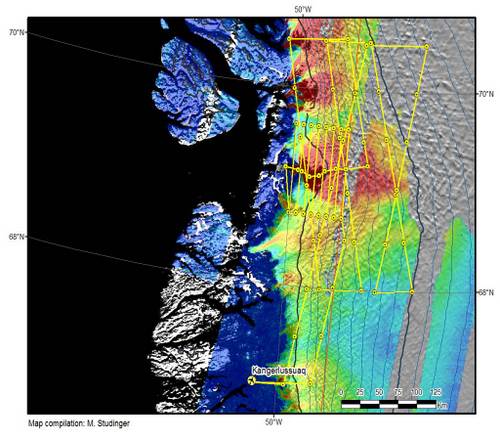

The crossing lines on the right are IceSat I tracks that were overflown to verify the data collected.

The crossing lines on the right are IceSat I tracks that were overflown to verify the data collected.

John also serves as the team’s meteorologist; although he is quick to point out he has no formal University training. Listening to his nightly weather briefs, it’s hard to tell. John’s knowledge comes from a solid physics and engineering background, John said, ‘If you can understand thermodynamics, you can apply that to understanding weather.’ He works closely with local meteorologists wherever the team is stationed. John's nightly weather briefings told me that he could be an excellent teacher.

I really enjoyed getting to know John and learn about what it takes to make Operation IceBridge work for everyone involved. Plus he’s a former high school cross country runner. You know I have a soft spot in my heart for anyone like that!