Servicing an Automatic Weather Station in Antarctica

Yesterday and today we were able to fly out to two Automatic Weather Stations (AWS), named Nico and Henry. Neither had been serviced in a few years and both needed some attention.

What do you do when you "Service" an Automatic Weather Station?

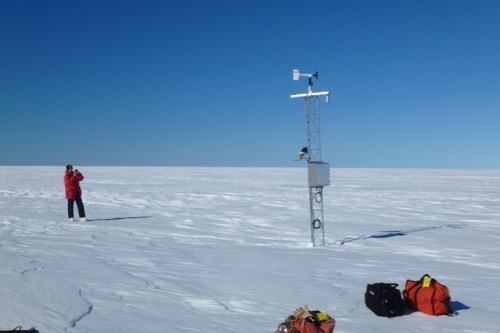

The first thing we do when we get off of the airplane or helicopter is to photograph the AWS before we touch anything.

Step one to servicing an AWS is to take pictures of the AWS before any work is performed.

Step one to servicing an AWS is to take pictures of the AWS before any work is performed.

Then we set up an extremely accurate GPS unit that will give us the exact coordinates of the AWS so that we know how much the ice sheet it is sitting on has drifted since it was last serviced. (We use that information to make informed guesses about where it SHOULD be when we need to find it again!) Some of the AWS can drift more than a kilometer per year! Measurements are taken of how high above the snow surface each of the instruments are. Generally the AWS has two temperature sensors (an upper and a lower), a humidity sensor, usually they include a snow depth sensor, an aerovane (a device that measures wind speed and direction), a solar panel, and an antenna. The antenna sends the data that is collected by all of those instruments (every few seconds!) up to satellites that then relays the data to computers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. It is then available for meteorologists and Climate Scientists (and you) to access.

Then...we DIG!

Why are you digging?

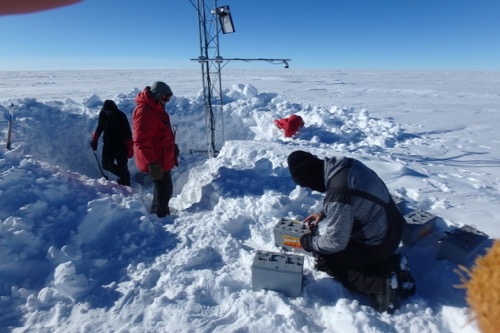

All of those instruments need electrical power. In the Austral summer, when the sun is shining 24 hours a day for 6 months, the AWS runs on solar power. The solar panel also charges a set of batteries (usually four, 70-pound batteries) that will run the system during the 6 months long winter when there will be no sun. Those batteries are in a big box that is buried in the ice just below the AWS tower. It is good for the batteries to be buried because the temperature is more constant under the snow than it would be sitting on the surface.

AWS need fresh batteries to make it through the harsh and frigid Antarctic winter.

AWS need fresh batteries to make it through the harsh and frigid Antarctic winter.

At some locations, a lot of snow accumulates and the battery boxes get buried deep in the snow. At the AWS called "Nico" that we serviced yesterday, we had to dig about seven feet down to get to the battery box!

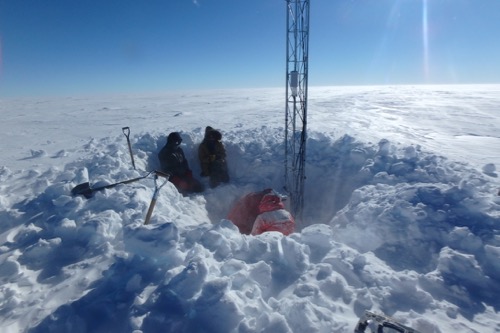

Due to snow accumulation, the battery boxes of AWS can be buried very deep in the snow and ice. This one, at an AWS called "Henry" was about seven feet deep!

Due to snow accumulation, the battery boxes of AWS can be buried very deep in the snow and ice. This one, at an AWS called "Henry" was about seven feet deep!

Once the box is found, uncovered and opened, the old batteries are replaced with new batteries. "Replacing the batteries" sounds easier than it is...trust me! Those things are heavy and are hard to lug in and out of a seven-foot-deep hole!

The snow is NOT easy to dig in. It is nearly as hard to dig in the snow as it is to dig in the ground at home, the difference is, that while the snow is almost as solid as the ground, it weighs much less.

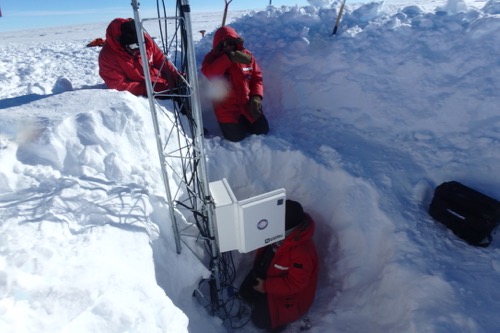

As we dig down, we have to be careful not to hit any wires that run from the instruments to the "Enclosure." The Enclosure is the brains of the AWS where all of the information is recorded on a "datalogger" and sent to the satellites through the antenna. At both Nico and Henry (the AWS we serviced yesterday and today) we had to replace the enclosure (upgrading to a newer model).

The enclosure is the brains of an AWS containing the "Data Logger" and linking all of the data that the instruments collect to the satellites.

The enclosure is the brains of an AWS containing the "Data Logger" and linking all of the data that the instruments collect to the satellites.

Being inside the hole is good and bad. It is generally out of the wind...which is good. But inside the hole is significantly colder than being on the surface...which is bad!

Several "Boondogglers" (Mike, Forest and Mandy) seek some shelter from the -50˚ windchill at "Henry" AWS near the South Pole.

Several "Boondogglers" (Mike, Forest and Mandy) seek some shelter from the -50˚ windchill at "Henry" AWS near the South Pole.

The instruments and the battery box are being connected to the enclosure at an Automatic Weather Station in Antarctica.

The instruments and the battery box are being connected to the enclosure at an Automatic Weather Station in Antarctica.

Raising the tower!

Dave and Elina (of the AWS team) have raised this tower and are now raising the instruments to their optimal heights above the ice.

Dave and Elina (of the AWS team) have raised this tower and are now raising the instruments to their optimal heights above the ice.

Depending on how much snow accumulation there has been since the AWS was last serviced, the top of the tower may need too be raised. To do that, we bring along several pieces of "tower section" (they come in various sizes, usually 5 or 7 feet) that can be attached to the top of the tower. If the tower is raised, all of the instruments, the battery box and the enclosure will be raised as well. None of it would be difficult back at home on a sunny warm day. But doing the simplest of these tasks, on a vast ice sheet at -20˚ with a howling 15 mile per hour wind and a windchill of -40˚, can be very challenging! Tiny nuts and bolts are nearly impossible to hold in a mittened hand and taking your had out of the mitten to use your fingers can be downright dangerous. Exposed skin, in -40˚ windchill can be frostbitten in moments so we are often quickly pulling gloves and mittens off to spin down a nut and then quickly putting our half-frozen hand back into the mitten to warm back up.

Replacing equipment

Some of the instruments and components need to be replaced occasionally. Sometimes they simply fail due to being in the extreme Antarctic environment, and sometimes they are just old and a newer version can do the job better. We replaced the entire enclosure on both of the last two AWS that we serviced.

Test and Fill

Once the batteries have been replaced, the tower raised, the required instruments have been replaced and raised, and everything has been checked to ensure that it is working properly and sending the correct data to the satellites, we fill in the hole!

Filling the hole

It is a strange phenomenon, but in the six or seven AWS that I have helped to service, not once was there enough snow to fill back in the hole! Weird.

Add new comment