Wishin and Hopin (and Liftin and Totin)

At the onset of this expedition, our planned itinerary included visits to nine AWS with each requiring various tasks ranging from inspection to raising sensors up the tower to protect them from snow accumulation to specific checks of sensors that have not been transmitting either any data at all or erroneous data. Five of the AWS (Lorne, Cape Bird, Minna Bluff, White Island, and Marble Point) were to be reached by helicopter flights and the remaining four AWS (Gill, Elaine, Sabrina, and Alexander Tall Tower) were to be reached by Twin Otter aircraft. Both sets of AWS visits have been hampered by unfavorable weather conditions and, for the Twin Otter flights, also by tainted fuel which had to be replaced at a local fuel cache before those flights could be rescheduled.

Up until Tuesday, November 21, one visit was made via helicopter to Lorne AWS where (as noted in a previous journal entry), several items were on the itinerary upon reaching Lorne but we had run into issues with the first task of extracting the battery box which had been sealed within its ice trench by a layer of ice on the bottom surface of the box. We had neither the tools nor the manpower to separate the battery box from the layer of ice and extract the battery box. Interestingly enough, on Saturday, November 18, we were placed on the helicopter schedule for a return flight to Lorne AWS, this time securing the necessary tools to handle the ice and recruiting two boondogglers (members from the community who volunteer their time and effort to help the scientists on their various expeditions). At our arranged time, we transported all of the required equipment to the helipad and entered the helicopter terminal to meet our boondogglers and await the necessary training prior to boarding a helicopter when we got the word that has become all too common. The flight was scrapped – not because of the weather at the helipad but this time because of the weather at Lorne AWS which was transmitted constant wind gusts of 20-25 knots, making accessibility of the helicopter to the landing site at Lorne a risky mission.

Yes, everything looked grim and glum… until yesterday! We finally got our opportunity to make great strides in our to-do list in the field. So, what I would like to do is take time in this journal post to talk about AWS – one that we are erecting at Phoenix Field and four others (outside of Lorne AWS) that are established and have been transmitting correct data on a continual basis. Although each of these four AWS were on the plan for inspection, one AWS (Minna Bluff) was transmitting incorrect temperature and wind speed data and we wanted to see what the problem was. I will be showing photos of each of the AWS , including Minna Bluff, so you can see exactly why we were having problems with the data.

At this point, I have had the opportunity to observe and become involved in various aspects of the AWS on various dates. In this journal, I would like to compile and discuss my observations with the AWS – starting from the beginning.

The Structural Framework of an AWS

The first stage in constructing an AWS in the structural framework consisting of a triangular tower that typically extends 10-15 feet from the ground. The tower comes in sections which can be attached so that the instrumentation can be raised as the snow accumulates over the years. In addition, a major challenge of the AWS framework is that the AWS tower must be stable enough to withstand the rather strong wind gusts that can occur for extended periods of time. To construct an AWS out in the field, a lengthy list of tools, equipment and hardware is required, in addition to segments of tower and all of the sensors and components related to the measurement of the scientific data to be acquired by the AWS. The planning process is rather involved to insure that not only the required hardware is identified and placed on the list for transport out to the field site, but also to include hardware and tools that might be needed for unexpected or unforeseen mishaps in the field, such as dropping small washers or bolts or needing a different-sized wrench.

The field site for the new AWS is Phoenix Field. Phoenix Field is the current airfield/runway for flights originating out of McMurdo Station to Christchurch, New Zealand. It is approximately 11 miles from McMurdo Station. On the date of the planned installation, all of the cargo required to construct an AWS is transported to the loading dock and then placed into the cargo bed of a truck – but not just any truck. We used a Mattracks vehicle. The wheels of the truck are replaced with treads similar to those found on tanks, allowing the vehicle to navigate the snow-covered and ice-topped terrains commonly experienced on the roads leading up the field sites where AWS are installed.

Mattracks vehicle used to transport equipment to the AWS site.

Mattracks vehicle used to transport equipment to the AWS site.

Of course, with such a cool looking vehicle that I knew I would probably never see again in my life much less ride in one, I had to get a picture of me standing next to it.

Me in front of a Mattracks vehicle.

Me in front of a Mattracks vehicle.

Once the tower is constructed according to the planned height, the tower must be anchored in order to keep it stabilized and upright for two reasons: (1) the tower with all of the sensors and attachments to the power supply must remain freestanding in order to continue collecting weather data under extreme weather conditions and, (2) the tower must be upright and aligned perpendicular to the surface as best as possible (using a level and line of sight) to ensure that any data dependent on orientation such as wind speed/direction be scientifically accurate. To accomplish this, the tower is stabilized by three guy wires (yes, it is spelled correctly), which are each anchored into an angled L-shaped bar called a deadman (again, it is spelled correctly), buried in a two-foot trench and packed with snow, as shown in the figure below.

A deadman buried within a trench.

A deadman buried within a trench.

Me tamping the snow on one of the trenches.

Me tamping the snow on one of the trenches.

Three deadmen (I believe that is the correct plural presentation of a deadman, and not 'deadmans') are required to secure the three guy wires to support the AWS tower. Below is the final product of the AWS tower infrastructure.

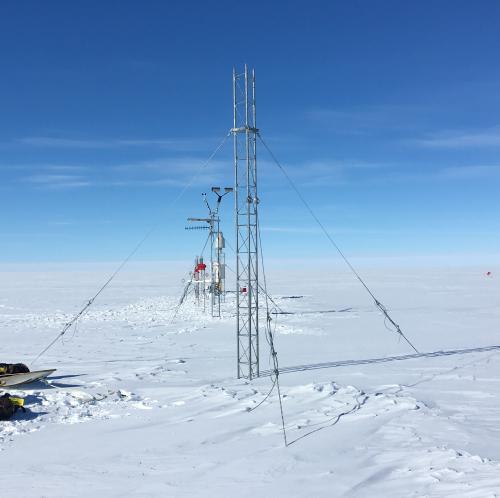

Completed infrastructure of an AWS.

Completed infrastructure of an AWS.

Installation of the AWS Power Supply, Solar Panels and Sensors

Once the tower is erected, the next steps that follow are: mount the sensors at appropriate positions along the tower supporting rods; connect the sensors to a data logger that will collect and transmit the weather data obtained by the sensors; mount a solar panel along the tower supporting rods that will transfer solar energy collected by the sun (remember, during the summer months, Antarctica sees virtually 24 hours of continuous sunlight) to a power supply; and finally connect the data logger control box and the solar panel to a battery box. The batteries within the battery box are solar powered which means they take the solar energy from the panel and then in turn convert it into electrical energy which powers the data logger and the connected sensors.

Of course, taking into account the sensors, the solar panel, the data logger control box, the antenna used to transmit the data from the data logger, the battery box and the batteries themselves, you would think that there is a lot of equipment and related hardware and tools to haul to the AWS tower. You would be right – not only is there a lot of equipment but combined it is heavy.

Cargo to be loaded for the Phoenix Field AWS.

Cargo to be loaded for the Phoenix Field AWS.

To facilitate the transport of all of this equipment, we checked out a pair of banana sleds – which make the transport of heavy equipment across the snow surface easier. Well, easier is a relative term considering that each battery is akin to a car battery and weigh 70 pounds per battery. The two batteries in the battery box are each 13 volts and are connected in parallel, similar to how houses are wired. The battery box that would be providing power to the AWS at Phoenix Airfield would require two batteries. We loaded up the two banana sleds with the equipment and began hauling through the snow.

Banana sled loaded with cargo for Phoenix Field AWS.

Banana sled loaded with cargo for Phoenix Field AWS.

Carol was amazing, lugging the heavier of the two sleds to the AWS and at record speed. I will admit that I was exhausted and Carol even came back to help me the last 30 feet. So, just how far did we travel with the banana sleds? In the photo below, draw a straight line path from the sled to the small speck in the distant background and that would be the truck that we drove out to the field! Anyway, enough complaining… there is work to be done!

Loaded banana sled with truck in the background!

Loaded banana sled with truck in the background!

Once the banana sleds have been pulled to the location of the AWS tower, everything must be unloaded, including the batteries. In the photos below, I am liftin a battery and then totin the battery (excuse the spelling – I am working within the theme of the journal post).

Me liftin a battery.

Me liftin a battery.

Me totin a battery.

Me totin a battery.

Carol donned her harness and began installing the sensors one by one, making sure that they were securely fastened to the tower supporting rods and that they were all level or perpendicular to the tower.

Carol in a harness installing the aerovane on top of the AWS tower.

Carol in a harness installing the aerovane on top of the AWS tower.

Our shadows were working just as hard on the Phoenix Field AWS.

Our shadows were working just as hard on the Phoenix Field AWS.

Maintenance and Repair of Functional/Operational AWS

As I mentioned in the introductory paragraph of this journal, the primary objective of my time in Antarctica was the opportunity to travel to functional/operational AWS and conduct routine maintenance evaluations. On Tuesday, we were booked on back-to-back helicopter flights which would eventually take is to five AWS. On our first leg of the trip, the helicopter pilot took us to Marble Point and Marble Point II (both within five minutes of walking distance between them) and Cape Bird, before flying home to refuel. Once refueled, we flew to Minna Bluff and then on to the AWS on White Island before we returned back to base.

GPS tracking map of our helicopter flight to five AWS.

GPS tracking map of our helicopter flight to five AWS.

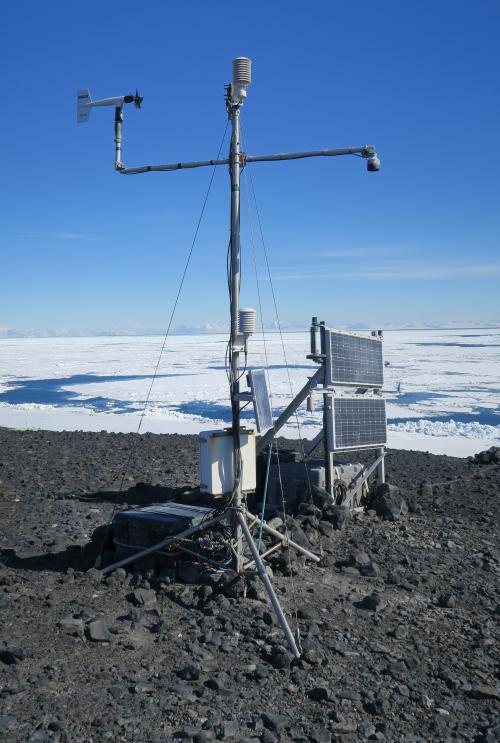

A photo of Marble Point AWS.

A photo of Marble Point AWS.

A photo of Marble Point II AWS.

A photo of Marble Point II AWS.

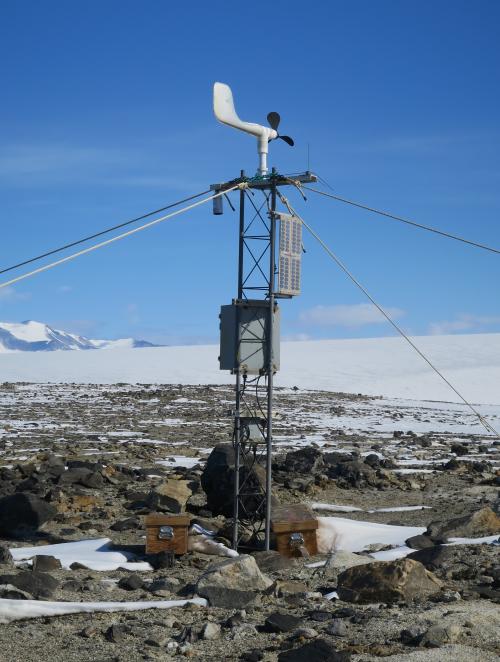

A photo of Cape Bird AWS.

A photo of Cape Bird AWS.

A photo of Black Island AWS.

A photo of Black Island AWS.

A photo of Minna Bluff AWS.

A photo of Minna Bluff AWS.

Now do you see what the problem might have been with Minna Bluff? It looks like Minna Bluff will be on the schedule for a return visit!

Today was a busy day, indeed, with a lot that was accomplished. However, the highlight of the day had to be my visit to Cape Bird. Why, you ask? Cape Bird is named for a reason. There are birds there. Like penguin birds. Many penguin birds. How many there actually were is hard to tell but if I had to render a guess, I would say upwards of 5,000 penguins. As we exited the helicopter, Carol made a comment that it "smelled like penguins." I wondered at that point, What exactly do penguins smell like? I didn't smell anything at first and then a couple of minutes later, I smelled it too. The smell was actually common to me as a Texan. If you have ever had the opportunity to visit a Stock Show and Rodeo at any time in your life, then you know exactly what penguins smell like. Just like that! Below are two photos of penguins that I was able to take. Penguins are truly fascinating birds, and I can see why they capture the imagination and curiosity of young and old alike.

The penguins at Cape Bird.

The penguins at Cape Bird.

More penguins at Cape Bird.

More penguins at Cape Bird.

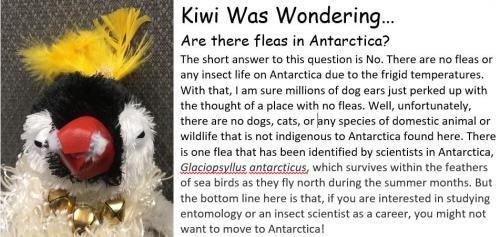

Speaking of penguins, Kiwi had another question on his mind:

Kiwi Was Wondering About...

Kiwi Was Wondering About...

Coming Up Next: Getting around McMurdo and local areas in such extreme weather conditions is not as bad as you would think... as long as you have the right vehicle!

Add new comment