Update

It’s a good thing we left early. We just missed a storm about a day or so behind us. We can feel some of the effects rocking and rolling on the edge of it out here, but it’s not nearly as bad as when we were transiting to Antarctica. This satellite image is a few days old and not quite to scale (we’re much smaller than the text and arrow) but I think it gets the point across.

Satellite Image with weather data for our location for the 4th week of April, 2015 from MODIS.

Satellite Image with weather data for our location for the 4th week of April, 2015 from MODIS.

A Closer Look at Glaciers

Over the course of our expedition, we’ve collected data in the regions of four different Antarctic glaciers: Dibble glacier, Totten glacier, Moscow University glacier/ice shelf and Frost glacier.

A map of our cruise track for NBP1503 by Chief Scientist, Dr. Frank Nitsche.

A map of our cruise track for NBP1503 by Chief Scientist, Dr. Frank Nitsche.

Some of these glaciers are melting at a rapid rate, while others are not. East Antarctica contains enough ice to raise sea level 11 feet if it were to all melt. The data collected on this expedition, once processed, analyzed, and incorporated into climate models will help scientists understand why some of the areas are melting while others are not, and help explain other impacts happening to these glaciers.

Sterling, 9th grade, wants to take a closer look at glaciers.

Sterling, 9th grade, wants to take a closer look at glaciers.

A glacier is a huge piece of very dense ice that exists year round. It forms from the buildup of centuries of snow, compressed under tremendous weight into dense ice. Sometimes the ice can become so dense it refracts light differently, leading to a distinct blue coloration rather than a white color. Air bubbles trapped in the ice can be hundreds of thousands of years old and, and when extracted provide vital information about Earth’s past climate.

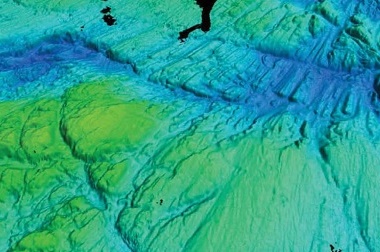

Despite, or rather because of their heavy weight, glaciers actually flow and move, grinding up rocks and shaping valleys as they slide along the ground. Glaciers move by basal sliding. The weight of the glacier creates high pressure and friction which can cause some of the ice to melt. This liquid water lubricates the bottom of glaciers, allowing glaciers to slide at their base. In Antarctica, using bathymetry we can see evidence of past glacier movement, like melt water channels and areas of sediment pushed by the glaciers, on the ocean bottom.

A view of the ocean bottom obtained from multi-beam bathymetry showing glacial lineations and subglacial meltwater features by Nitsche et al, 2012.

A view of the ocean bottom obtained from multi-beam bathymetry showing glacial lineations and subglacial meltwater features by Nitsche et al, 2012.

As glaciers slide off the continent into the ocean they become known as ice shelves. Glaciers can also break or calve, forming icebergs. If an iceberg is over 10 knots across, they get their own formal name from the National Ice Center.

A city-sized ice berg in the Southern Ocean. Photo by Dominique Richardson.

A city-sized ice berg in the Southern Ocean. Photo by Dominique Richardson.

Try it at home

Make your own edible glacier (glacial ice cream sundae)

You’ll need: blue jell-o, vanilla ice cream, cool whip or whipped cream, crumbled oreo cookies, a clear cup and a spoon.

- Sprinkle some crumbled oreo cook on the bottom of your clear up. This is the rocks and dirt of the ground.

- Lay down a layer of blue jell-o. This is the dense ice formed from hundreds to thousands of years of condensed snow. It looks blue because it is so dense it refracts light differently than uncompressed white looking ice.

- Lay down a layer of ice cream. This is snow that’s fallen tens of years ago. It’s dense, but not quite as dense as the blue ice yet. It will eventually turn into that dense blue ice!

- Lay down a thin layer of cool whip/whip cream. This is light, fluffy, freshly fallen snow. It contains lots of air, keeping it light weight and giving it a white color. Eventually it will be compressed into thicker ice and eventually dense blue ice.

- Sprinkle some oreo cookie “rocks” in with the layer. Sometimes dirt and rocks get caught in the glacier and can get carried hundreds of miles away as the glacier moves.

- Now that you have a complete glacier, let it “slide” into your mouth!

A small town-sized iceberg with a distinct line of trapped sediment and debris. Photo by Guy Williams.

A small town-sized iceberg with a distinct line of trapped sediment and debris. Photo by Guy Williams.