Would a Plocamium by any other name be as interesting to Sabrina Heiser… probably.

The majastic and always beautiful Plocamium.

The majastic and always beautiful Plocamium.

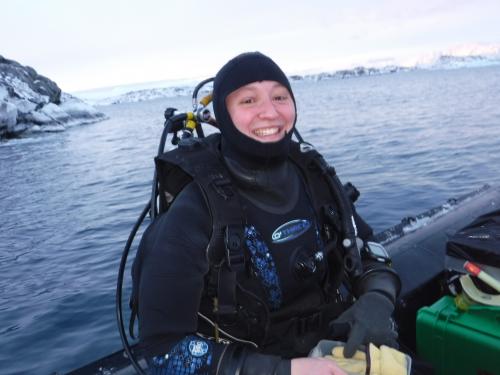

The smile Sabrina has while talking about Plocamium cartilagineum tells you she is really, really interested in studying these red algae.

Sabrina getting ready to dive.

Sabrina getting ready to dive.

She first became interested in Plocamium when she was looking at PhD programs and read a proposal that was going to study both the ecology and chemistry Plocamium. Sabrina has been SCUBA diving since a very young age and her PhD work allows her to use this skill during the collection of Plocamium. Although this type of red algae has worldwide distribution, it actually presents cryptic speciation, which means that even though the individuals may look alike, genetically they are very different. Sabrina’s PhD work entails lots of different aspects of study, but her work this Antarctic season deals mainly with trying to discover whether the chemical defenses of the Plocamium is dependent on the location where the red algae is growing. Last year, she took individual plants with specific chemotypes from one area of the Palmer Station dive area and transplanted them to other areas.

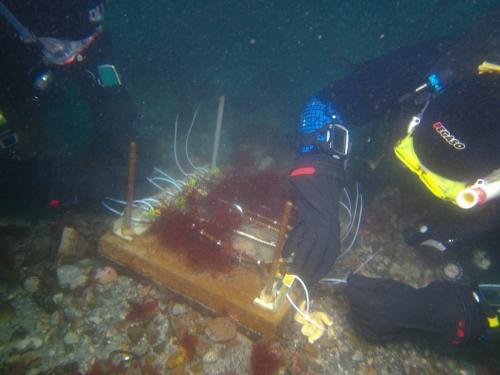

Sabrina and Andrew working on one of the transplanted substrates.

Sabrina and Andrew working on one of the transplanted substrates.

Then it was a long wait to travel back here the next year, and hope icebergs had not disturbed them or that the Plocamium would grow or even the zip ties they were held down with might break off and her algae would float away. She was super excited to see most of her transplanted blocks were intact, to hopefully get the data she needs. Plocamium has a super cool life cycle. The individual seaweeds are either male or female haploids or a nonsexual diploid. The female haploids are fertilized by male haploids and grow circular structures called cystocarps that eventually release spores that grow into the nonsexual diploids, the diploids then grow stichidia that release spores and grow into either male or female haploids.

Female haploid with cystocarps.

Female haploid with cystocarps.

Sabrina has discovered (or should we say not discovered) something very interesting – that is she has never, to her knowledge, found a male haploid seaweed. The researchers are not sure why this is, but excitingly enough they have collected some stichidia that have been released by a diploid seaweed, and so if Sabrina can't find her man, she hopes she can grow one back at the lab. Godspeed Sabrina, Godspeed!

Diploid with stichidia.

Diploid with stichidia.

Add new comment