In order to fully understand the Deep Roots experiment, there are a few things to review about plants (and how the Arctic places limits on plant growth). Sure, we all know the basic parts of a plant – roots, shoots, leaves – and we also know that plants require sunlight and CO2 to make glucose (photosynthesis). But there’s a little more to it then that.

Plant growth in the tundra

The glucose created by photosynthesis is used for building structures like stems, leaves, flowers, and, of course, roots. But just like in other living things, plants need more than just Carbon, Oxygen and Hydrogen to build structures; Nitrogen and Phosphorous are fundamental to the structure of DNA and proteins, which is why a lot of commercially abundant plant fertilizer is saturated with N and P. And if you’ve ever applied fertilizer, you know that you apply it to the soil – because it’s the roots that take up those minerals to promote the plant’s growth.

A list of ingredients from commercially available organic fertilizer, note that the two main ingredients are Nitrogen and Phosphorous. Source: AGgrand.com

A list of ingredients from commercially available organic fertilizer, note that the two main ingredients are Nitrogen and Phosphorous. Source: AGgrand.com

All organisms build structures as they grow, but plants are limited by the amount sunlight they have access to (just like animals are limited by the amount of food they ingest). In the high Arctic, there is no sunlight for nearly half of the year, so plants must adapt to this limitation accordingly. Common adaptations across the tundra include being fairly low to the ground (it takes a lot of time and energy to grow tall), small waxy leaves (to minimize water loss) and growing close together (to help insulate and offer protection against high winds).

Bright tundra flowers in the height of summer. Notice how close to the ground the flowers are.

Bright tundra flowers in the height of summer. Notice how close to the ground the flowers are.

A fairly typical shot of open tundra. Note how close together the plants are, sort of like a carpet.

A fairly typical shot of open tundra. Note how close together the plants are, sort of like a carpet.

Typical tundra plant leaf, notice how shiny and waxy the outer covering is.

Typical tundra plant leaf, notice how shiny and waxy the outer covering is.

In addition to the lack of sunlight, these plants also have to deal with a unique soil type – permafrost. Permafrost, commonly called “Earth’s Freezer” is soil (and whatever dead organic material is in that soil) that remains permanently frozen throughout the year – and can remain frozen for thousands of years. This means that the permafrost layer is a storehouse of some of those vital elements to plants – particularly Carbon and Nitrogen.

The layer of soil above the icy permafrost, the active layer, is the layer where plants can put down roots and grow. The depth of the ice layer can vary along the tundra due to many factors (which scientists are still trying to understand), so the depth of the active layer and plant roots can vary as well.

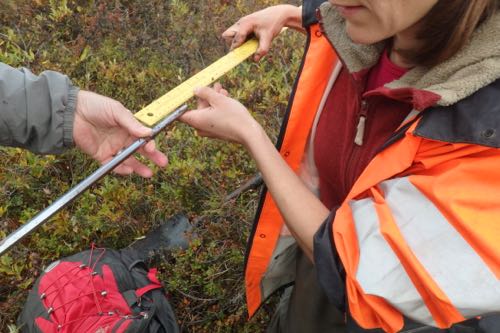

The thaw depth of soil is measured to see how deep the permafrost is below the active layer.

The thaw depth of soil is measured to see how deep the permafrost is below the active layer.

A tundra soil monolith showing the dense network of roots in the organic soil layer.

A tundra soil monolith showing the dense network of roots in the organic soil layer.

An extreme close up of some very fine roots found within a soil monolith.

An extreme close up of some very fine roots found within a soil monolith.

Deep Roots

Since the name of this project is Deep Roots it’s pretty obvious that the team wants to understand the root structure of these tundra ecosystems. To do this, there are several questions that need to be examined. Below are just a few of the questions that the team is investigating:

What types of plants are putting down roots in the tundra?

How deep are different types of roots throughout the active layer?

What microorganisms (fungi) live on the root systems of some of these plants?

How quickly does Nitrogen move through a plant’s system and where does it ultimately “end up?”

How will a warmed environment have an effect on questions 1-4? Will it have an effect at all?

If warmed environments DO show different answers to any of these questions, what predictions could we make in light of our changing climate?

Keep reading my journals as I attempt to explain how the research team is collecting data to try and answer some of these questions!

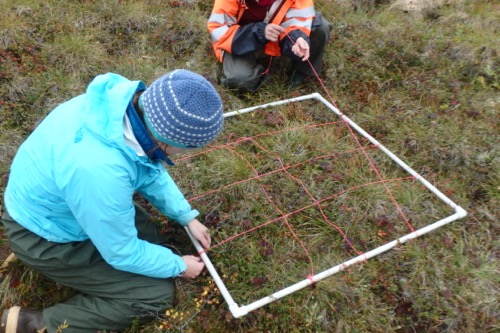

Just why is this frame being placed over the Alaskan tundra? It’s part of the experiment!

Just why is this frame being placed over the Alaskan tundra? It’s part of the experiment!

Comments