Top of Tumbledown Mountain, Weld, Maine. Photo by Erin Towns.

Top of Tumbledown Mountain, Weld, Maine. Photo by Erin Towns.

Simple Questions, Complex Answers

”Hey Ms. Towns, can ice sheets and glaciers really fully melt and disappear?” ”Why should we care? We live in Maine.” ”I mean, is it really going to happen up there in the Arctic?”

Students pose big questions that at first glance, look so simple. However, twenty one years in a classroom has taught me that the simplest questions are often the most complex to teach. My teaching style primarily focuses on relevancy of content to students’ personal lives. Everything we do in the classroom connects to real life. Without this lens, everything means nothing. Teaching about real issues surrounding environment and geopolitics of the Arctic requires a solid understanding of one’s own locality first. Concrete understanding of the backyard fosters creativity, buy in, and connection to life beyond it. The probability of students taking informed and responsible environmental, political, economic, and social action in the future depends on understanding the connection and importance of the Arctic to Maine without a doubt.

Dr. Seth Campbell gives a presentation to students about glaciers in Maine. Photo by Erin Towns

Dr. Seth Campbell gives a presentation to students about glaciers in Maine. Photo by Erin Towns

So where to start to answer student questions? Ah yes, the backyard. Considering my limited knowledge and understanding of Maine geology and topics involving the cyrosphere, it became obvious that expert help was needed. Contacts at the University of Maine at Farmington, University of Maine Orono's Climate Science Institute, Maine Geographic Alliance, and University of Southern Maine were patient and generous with time and effort. They provided examples, answered a myriad of questions, explained characteristics, and gave recommendations that were super helpful. A very special thanks goes out to Dr. Sarah Das, Dr. Seth Campbell, and Sue Lahti for their valuable time and efforts to assist.

Surficial Geologic History of Maine

According to the Maine Geological Survey, continental glaciers similar to today’s Western Greenland Ice Sheet extended across Maine several times during the Pleistocene Epoch (2.5 million to 10,000 years ago). The most recent glacial episode in Maine began about 35,000 years ago when the Laurentide Ice Sheet that covered much of northern North America expanded southward into New England. Sea levels at the time were hundreds of feet lower than today due to the water being tied up in glaciers. It was several thousand feet thick. The sheer weight of the glacier was so much that it pushed down the land several hundred feet. Slow-moving glacial ice changed the landscape as it scraped over mountains and valleys. Rock debris was carried for miles and dropped when the glacier retreated. Sand, gravel, rounded mountaintops, moraines, glacial erratics, stony till, meltwater streams, glacial lakes, and modern ponds are the evidence. Maine is even home to one of the largest glacial erratics in the world, Daggett Rock.

*Local legend has it that Daggett was a woodsman down on his luck. He climbed the 8,000 ton rock and was cursing God for his bad luck during a bad storm. Upon Daggettt taking his god’s name in vain, a lightening bolt struck the rock splitting into three parts. Geologists have a different theory. Mainly that the rock was plucked from nearby Saddleback Mountain and deposited by the retreating ice sheet where it stands now. Photo by Erin Towns*

*Local legend has it that Daggett was a woodsman down on his luck. He climbed the 8,000 ton rock and was cursing God for his bad luck during a bad storm. Upon Daggettt taking his god’s name in vain, a lightening bolt struck the rock splitting into three parts. Geologists have a different theory. Mainly that the rock was plucked from nearby Saddleback Mountain and deposited by the retreating ice sheet where it stands now. Photo by Erin Towns*

Glacial till consisting of unsorted glacial sediments blanket Maine. Photo by Erin Towns

Glacial till consisting of unsorted glacial sediments blanket Maine. Photo by Erin Towns

Mt. Katahdin’s Chimney Pond is a tarn, a lake found in the basin of a cirque. The Chimney Pond cirque is evidence of glacial processes including freeze thaw and mass wasting. Photo by Erin Towns

Mt. Katahdin’s Chimney Pond is a tarn, a lake found in the basin of a cirque. The Chimney Pond cirque is evidence of glacial processes including freeze thaw and mass wasting. Photo by Erin Towns

Blueberry fields found on hills with well drained soil, are a product of the extensive sand and gravel deposits left by the rushing rivers of glacial meltwater, under and near the ice front. Photo by Erin Towns.

Blueberry fields found on hills with well drained soil, are a product of the extensive sand and gravel deposits left by the rushing rivers of glacial meltwater, under and near the ice front. Photo by Erin Towns.

Moral of the story: Ice sheets and glaciers once existed in Maine and they disappeared. It can happen again because that is what Earth systems do, they change and when they do the effects are unbelievably large. Currently there are massive changes happening in Polar regions that scientists collect data about linking changes in climate to human activities around the globe. There are a few reasons why we should be paying more attention to this.

Sea Level Rise in Maine, That’s Why We Should Care

”Maine has taken bold steps to advance their Arctic connection, including recent participation in The Arctic Circle Assembly and relationship with Eimskip, an Icelandic international shipping company which has a regional hub in Portland.” Quote taken from U.S. Navy’s Strategic Blueprint For The Arctic. Photo by Erin Towns

”Maine has taken bold steps to advance their Arctic connection, including recent participation in The Arctic Circle Assembly and relationship with Eimskip, an Icelandic international shipping company which has a regional hub in Portland.” Quote taken from U.S. Navy’s Strategic Blueprint For The Arctic. Photo by Erin Towns

According to the Maine Policy Review, “Maine has numerous important economic and strategic interests in what goes on in the Arctic even though it does not border it. Portland hosted the Senior Arctic Official meeting in 2016 which allowed Maine to highlight its successful pivot towards the north. Senator Angus King became co chair of the Arctic Caucus in 2015. Maine sent a large delegation to the Arctic Circle Assembly in Iceland during 2015. Maine sends over 50% of its exports to Canada. Maine struck a deal with Iceland’s largest shipping firm, Eimskip to locate its North American headquarters to Portland. "All of this indicates that Maine indeed, has vested interest when it comes to a warming climate and the serious implications it could have most notably on sea level rise. Maine Governor Janet Mills addressed the Climate Action Summit before the UN General Assembly and attended the 2019 Arctic Circle Assembly. She has continued to focus on Arctic issues by collaborating with Arctic countries like Finland and Norway in areas of focus surrounding bioeconomic innovation, forest health, sustainability in the face of climate change, renewable energy technologies, and scientific cooperation.“

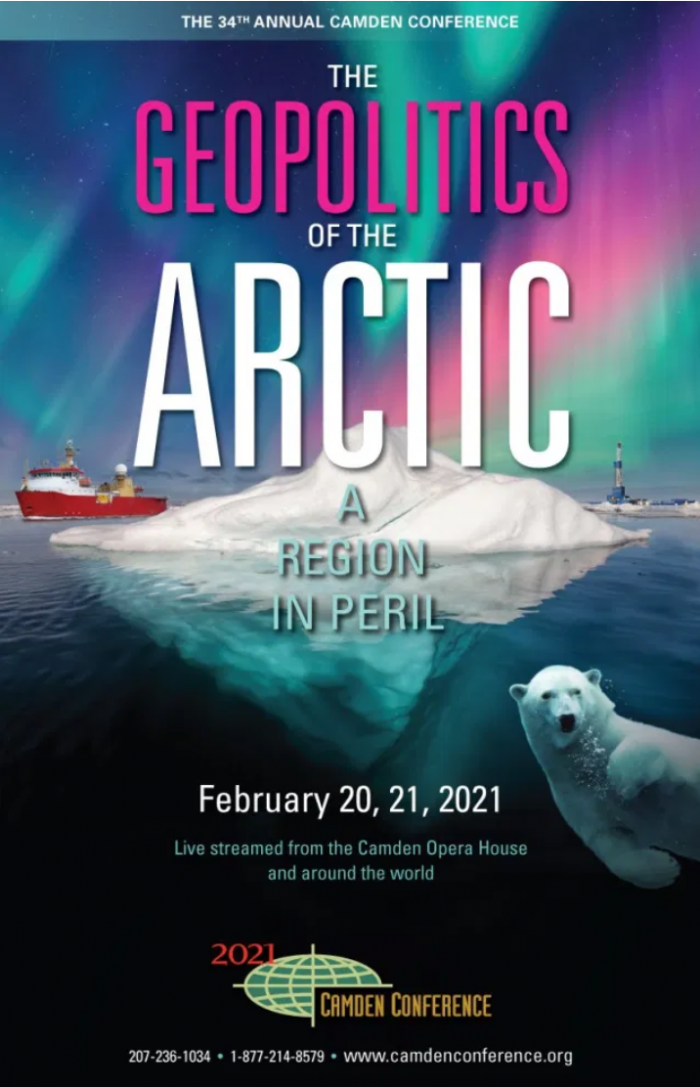

The 2021 Camden Conference will explore the Arctic and examine how retreating ice mass impacts the balance of global power and competition. Photo by Camden Conference.

The 2021 Camden Conference will explore the Arctic and examine how retreating ice mass impacts the balance of global power and competition. Photo by Camden Conference.

Every year on the Maine Coast a foreign policy event is held called The Camden Conference. Its mission is to foster informed discourse on world issues. In 2018 I listened to a presentation entitled, The “3 Geos” Reshaping Our World, given by Cleo Paskal, Associate Fellow in the Energy, Environment, and Resources Department at Chatham House. ”Thee reason geophysical change is an issue is because as humans we tend to build into the environment that is already there. Understanding that will be key to understanding problems going forward. It is part of the way that we as humanity develop, expand and provide economic opportunity.”

This ArcGIS Online map shows the 132 Maine cities and towns that sea level rise is projected to affect. Photo of ArcGIS Online Map created by Erin Towns.

This ArcGIS Online map shows the 132 Maine cities and towns that sea level rise is projected to affect. Photo of ArcGIS Online Map created by Erin Towns.

Maine citizens have definitely built into the environment. Sea level rise is projected to affect at least 132 Maine cities and towns, affecting coastal businesses, homes, wildlife habitat, transportation systems, and some of the state’s treasured places according to an analysis done by the Natural Resources Council of Maine. A 1 meter rise is projected to take out over 20,000 acres and a 6-meter rise, over 127,000 acres.

Pemaquid Point, Bristol, Maine. Photo by Erin Towns

Pemaquid Point, Bristol, Maine. Photo by Erin Towns

Maine has 3,478 miles of coastline, excluding islands, and its communities and economy (tourism, real estate, shipping, and fishing industries) are concentrated on or near the coast. As such, sea level rise, coastal, and riverine flooding are of significant concern. The Governor’s Office of Policy Innovation and the Future created storm models that, “estimated concurrent effects of storm surge combined with sea level rise (to 1/6 feet above 2000 levels by 2050) and ran thousands of simulations to estimate damage to buildings and job loss from 2020 to 2050. Based on the combination of lea level rise and storm surge, the median scenario (I.e., the point at which half of the scenarios are worse and half are better) would result in 21,549 fewer jobs in 2050 than in the absence of flooding impact.” Rising sea levels can impact infrastructure, fishing, shipping, clean energy, ocean stewardship, sustainable development, maritime safety, emergency response, and rural connections and as such, demand significant consideration and action.

Maine’s connection to national interests in Arctic are outlined in the US Navy’s recently released, Strategic Blueprint For The Arctic. The publication stresses Maine’s critical strategic importance in light of future U.S. priorities in the Arctic Priorities include maintaining an enhanced presence, strengthening cooperative partnerships, and building a more capable Arctic naval force. Maine and Alaska are the only two US states mentioned in the blueprint. Throughout the publication, the Arctic Region is referred to as ”The Blue Arctic” validating long term impacts of the changing Arctic climate. What is happening in Greenland is evidence.

Greenland Subglacial Tremor Project

The Greenland Ice Sheet is melting at an alarmingly rapid rate. According to a 2019 study from NASA and the European Space Agency which can be found on NASA’s Global Climate Change website, Greenland has lost 3.8 trillion tons of ice between 1992 and 2018. ”The findings, which forecast an approximate 3 to 5 inches (70 to 130 millimeters) of global sea level rise by 2100, are in alignment with previous worst-case projections if the average rate of Greenland’s ice loss continues.’. The Greenland Ice Sheet holds enough water to raise the sea level by up to 24 feet.

My participation in the Greenland Subglacial Tremor Project is in part, as translator and communicator of the work of Dr. Sarah Das and a team of scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Boston College, and UCSD. Dr. Das is an Earth Scientist who studies glaciology and paleoclimatology and the role of the cyrosphere in the Earth system. Her research topics include the reconstruction of past climate from ice-cores, understanding and researching polar ice sheet mass balance and ice dynamics, exploring the interaction between the coupled cryosphere-atomosphere-ocean systems, and investigating biochemical processes in polar environments. What is interesting is that her work relating to the Greenland Ice Sheet’s contribution to sea level rise is something that is integral to understanding the basis for possible future social, economic, and political costs for Maine.

Dr. Sarah Das, Earth Scientist studies geology and paleoclimatology in Polar regions. Photo taken from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Website.

Dr. Sarah Das, Earth Scientist studies geology and paleoclimatology in Polar regions. Photo taken from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Website.

This study will improve understanding of how increases in surface runoff will influence ice flow and subsequent loss of water mass from the Greenland ice sheet to the oceans. She has observed first hand some pretty incredible phenomena including supraglacial lake drainage that may be affecting acceleration of ice flow and melting. Scientists like her are trying to better understand glacial hydrology and Greenland’s potential response to climate change. They are trying to figure out time scale and pathways through which meltwater reaches the ice sheet’s base and its consequence on something called basal motion, or in simple terms, the act of a glacier sliding over the bed due to meltwater under the ice acting like a lubricant.

Seismic and GPS arrays are systems of linked seismographs arranged in geometric patterns to increase sensitivity to earthquake detection. Dr. Seth Campbell holds a Trimble GPS antenna. Photo by Erin Towns

Seismic and GPS arrays are systems of linked seismographs arranged in geometric patterns to increase sensitivity to earthquake detection. Dr. Seth Campbell holds a Trimble GPS antenna. Photo by Erin Towns

The expedition team uses seismic tremor to quantify seasonal changes in the subglacial hydrologic system and ice surface velocities. Fracturing and turbulent water flow within and beneath glaciers radiate seismic waves that can be used to monitor what is happening. The team will deploy seismic and GPS arrays on the Western Greenland Ice Sheet, which is currently the fastest melting ice sheet in the world.

Bring Your Own Chair

Excuse me, can I squeeze in here right next to you please? Thank you so much! I would like to talk to you about the Arctic and education. Photo by Erin Towns

Excuse me, can I squeeze in here right next to you please? Thank you so much! I would like to talk to you about the Arctic and education. Photo by Erin Towns

Although COVID changed the timeline for our PolarTREC cohort and expeditions, we were warned at the beginning that having patience was going to be absolutely essential. I do not know at this point for sure when we shall see Greenland. The big gift in this has been the opportunity to prepare well, learning as much as possible about glaciers, environment, and geology, finding ways to understand content using visual arts, and beginning the process of networking to ensure that the Polar regions will receive much more attention in local and state education systems. This requires also getting a seat at the table in places where teachers don’t normally sit. With the time I have over the next year, I’m going to be bringing my own chair. Lawmakers, environmental organizations, educational institutions, and The Governor’s Office, are a few places to start.

This section will accompany every journal posting from here on out to share stories and strategies that we are going to try to pull off. Not sure if it will succeed or not, and frankly we have a lot to lose if nothing is done. So, here goes . . .

Idea #1 - Every Friday our students email Maine’s U.S. Representatives and Senators, sharing stories about what they are learning about the Arctic. It is our sincere hope that we can get a meeting or Zoom conference with all of them to keep students engaged and informed about upcoming legislation, or economic contracts related to the Arctic - Maine connections. This also teaches students about the process of how to engage politicians and policy makers and encourages ongoing future civic participation.

Idea #2 - After excursions out and about, I created an opportunity for students to explore their own backyards in Auburn and the surrounding area. Students were introduced to photography and editing techniques, the history or surficial geology of Maine, and viewed images I gathered to learn how they too could spot evidence that glaciers and ice sheets were once right here. Students collected their own photos out and about in their communities. All photos were uploaded to one shared document and captions were added explaining each feature and how it related to glaciers or ice sheets in Maine. Students plotted points on a Google MyMap and added pictures and captions in map notes. This was used in a Maine Cultural Heritage course lesson relating geography and geology to social character development throughout Maine’s history. The assignment also served as a foundation to develop observational skills that will be used for a future collaborative project related to sea level rise in Maine. Development of lessons using ArcGIS Collector are in planning stages currently.

Next posting will feature stories from a road trip on Maine’s Route 1 and classroom strategies used to run an Arctic Council Simulation for high school students.

Comments

Add new comment