At the beginning of the school year I ask my students to describe what they think a scientist looks like. Their pictures resemble the results you get if you do a google image search for "scientist" see for yourself . I found myself wondering what Terry Palmer, the research scientist I will work with in Antarctica, was like as I drove four hours to Corpus Christi, Texas.

I found Terry outside of the Harte Research Institute at the Texas A & M University at Corpus Christi (TAMUCC). He had just returned from a boat trip and looked nothing like my students' or google's idea of a scientist. He wore sunglasses and sandals and seemed like someone you would more likely meet surfing at the beach than working in a lab. After helping him clean up his boat, Terry gave me a tour of his research facility.

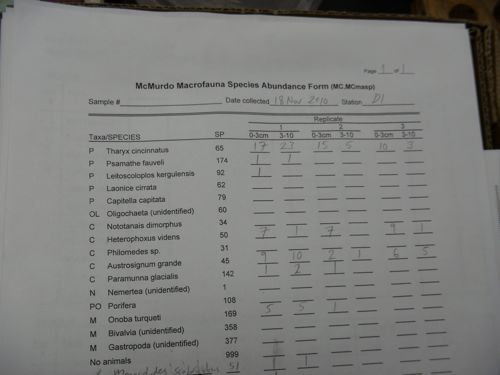

A carefully marked data sheet sitting next to a microscope caught my eye. Terry explained how scientists back at TAMUCC record the number and types of organisms found in sediment samples collected at McMurdo. After years of collecting this data, the research group can infer the health of the species and how their populations are changing.

Scientists record the numbers and types of macrofauna found in sediment samples from McMurdo.

Scientists record the numbers and types of macrofauna found in sediment samples from McMurdo.

Like an iceberg, whose mass resides mostly under the surface, the majority of the work for the McMurdo research project takes place back in the U.S., not on the ice in Antarctica. When I think of polar research I imagine scientists in diving gear and big red coats collecting samples amidst an icy backdrop. However, hidden under the exciting data collection process is the less glamorous and tedious analysis conducted in less exotic places like Corpus Christi and College Station, Texas.

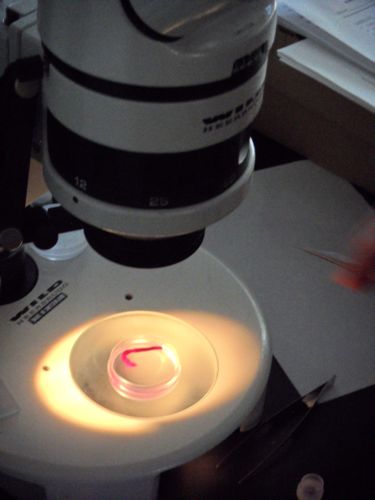

However a little glamour can be found in the excessively pink color of the organisms examined at the lab. Benthic critters like the worm shown below are dyed bright pink to help identify them. This worm is known as Euchone analis, which is found in the Arctic, North Pacific and North Atlantic, as well as Antarctica. It is a polychaete. Polychaetes are a type of annelid (segmented worm) that have bristles or hairs along their body. This makes sense since "poly" means many and chaetes comes from the Greek word for hair. You need a stereoscope to clearly see the tiny hairs, but they're there!

Tiny hairs on the dyed-pink polychaete are visible using a stereoscope.

Tiny hairs on the dyed-pink polychaete are visible using a stereoscope.

After touring the lab, we picked up Terry's 15 month old daughter, Scarlet, from daycare. We met his wife and other friends at the beach in Port Aransas, where I was able to enjoy a cool ocean breeze that my fellow Austinites would be very envious of since it was hot and muggy in Austin. At dinner I was able to get to know Terry's wife, Sally, who had also been to Antarctica working on the project that I will work on. It was great to hear stories about Antarctica and pick up tips on what to pack and how to manage on the ice.

From left to right, Michelle, Sally, Terry and Scarlet Palmer, enjoy the open house at the Marine Science Institute.

From left to right, Michelle, Sally, Terry and Scarlet Palmer, enjoy the open house at the Marine Science Institute.

The next morning we visited the open house event at the Marine Science Institute (MSI) at the University of Texas, where Sally works. Every year my colleague and I take students to MSI to explore the ocean and learn about marine biology. Although it is very different from Antarctica, there are some similarities between the benthic ecology (organisms living in and on the sea floor) of Antarctica and the Gulf of Mexico . I hope to make those connections clear when I return to MSI with my students in October.

Michelle tries to eat a Bonnethead Shark at the Marine Science Institute.

Michelle tries to eat a Bonnethead Shark at the Marine Science Institute.

While driving back home to Austin, my brain was spinning from all the things I had learned about the project and the new ideas I had for my students!