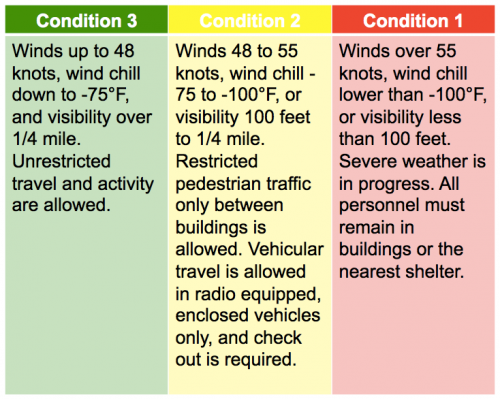

Well it was bound to happen eventually – whether that was going to be in the field or here at McMurdo was the question – we are moving towards Condition 1 today here on Ross Island. Weather here on Ross Island is broadly broken into three main categories defined by temperature, wind chill, and visibility. The McMurdo Weather Office issues weather forecasts every six hours for McMurdo Station (and more often if it is requested) and daily forecasts for field parties out in field camps so that they can use that information to determine what they will be doing for the day (or not doing as the case may be). In addition to the weather forecast, the Weather Office issues a Weather Classification that restricts movement and activities as the weather deteriorates. The weather classifications are divided into three categories:

As the weather changes (and it always seems to), the McMurdo Weather Office issues forecasts and classifies the conditions in one of three ways to inform participants what sort of activities and movement are allowed.

As the weather changes (and it always seems to), the McMurdo Weather Office issues forecasts and classifies the conditions in one of three ways to inform participants what sort of activities and movement are allowed.

Once we are in the field, Gordon Hamilton (the principal investigator and the team leader) will make a determination for what activities are permissible for the day. With 19 seasons on the ice here in Antarctica (and the 3rd season for this particular project), that experience allows Gordon to have a pretty good handle on the way the weather conditions can dramatically change. If the weather looks iffy, he will call into the McMurdo Weather Office and request a local forecast and then make the determination.

During the winter months the weather is more consistent – this is a result of even heating of the ocean and the continent. With the arrival of the sun, the surface air temperature over the oceans increases – this increase in temperature causes the warm air to rise (warm things having a lower density and hence rise like a hot air balloon). As the warm air rises, cooler, denser air rushes in to take its place and here in Antarctica that air is racing in from the interior and down the slopes and ice shelves. These winds are called katabatic and are most commonly found here in Antarctica and in Greenland – both places where the high ice sheets provide for uninterrupted winds to blow down to the coasts. When constricted through a valley the winds have been known to exceed hurricane force and can exceed 150mph!

In 2010, John Goodge, a professor of geological sciences at the University of Minnesota-Duluth, and Jeff Vervoort, an isotope geochemist from Washington State University, wrote for the New York Times about their research expedition in Antarctica and, in particular, one of the days that they encountered katabatic winds:

"Late Wednesday afternoon we had a sudden — literally within minutes — turn around in the weather, when the winds reversed direction, a white wall of blowing snow descended on camp and the wind speed jumped high enough to make you lean into it. That lasted most of the night without letup, yet I had a fairly good sleep in my tent despite the incessant flapping of the tent fly"

From what the team says, this will be our situation at least a few times this season as we head over to the Ross Ice Shelf and the McMurdo Shear Zone. There is not a doubt in my mind that while I sit inside my tent and listen to the wind whipping around me and pressing in on the sides of the tent, that I'll be composing my own journal entry to describe these seasonal winds of Antarctica.

Comments