Speed 9.5 knots (kts) Course 73.8 ° Location 71.16° N, 144.05° W Depth 2116 meters

SPECIAL FEATURE DISCUSSION:

(see previous journal for the questions.)

A ship's heading is the direction it is pointed in, while its course is the direction it is traveling in over the sea floor. On our navigation screens the course is abbreviated COG for Course Over Ground.

The two can be different due to currents & winds. For example, if the ship is heading east but there is an equally fast current from the north the course will be southeast.

TODAY'S JOURNAL:

I was pretty fired up yesterday to find out that we were getting set for the first bottom sampling watch of the cruise. Recovering sea floor samples is one of the primary activities our expedition is charged with accomplishing (along with gathering bathymetry and seismic data.) Yesterday the senior scientists looked over maps and seismic data taken from a previous cruise to select sampling sites. Their hopes were to find areas that may have rock near the surface that our coring gear could reach. Our first site was a little bump that sticks up about 300 meters from the sea floor with its top a little over 2500 meters deep.

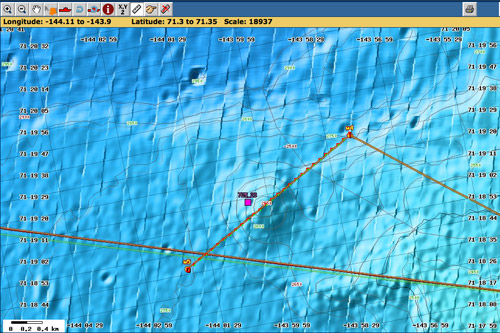

Bathymetry of the first sampling area. The bump in the middle is our target and the lines are guides for navigating the ship called track lines. After cruising over the bump to map it in high detail the ship returned to hold position over the coring site.

Bathymetry of the first sampling area. The bump in the middle is our target and the lines are guides for navigating the ship called track lines. After cruising over the bump to map it in high detail the ship returned to hold position over the coring site.

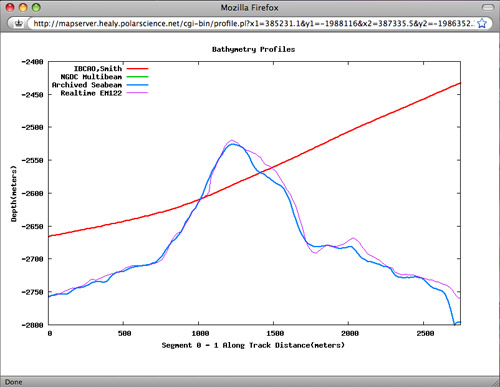

A sea floor profile of the sampling 'bump'. The red line is what traditional navigation maps indicate is there but the blue and purple lines are derived from high-resolution seafloor mapping systems on the Healy.

A sea floor profile of the sampling 'bump'. The red line is what traditional navigation maps indicate is there but the blue and purple lines are derived from high-resolution seafloor mapping systems on the Healy.

The bridge was sent coordinates of the bump and a track line to navigate over it so we could re-map the details of the feature with our subbottom profiler and multibeam swath sonar. Then we doubled back over the spot and for the next several hours the folks navigating the ship kept us in place as best they could, countering currents and winds with the ship's propellers and bow thruster. It was odd because at the surface we were moving through the water but relative to the sea floor we were standing still. It was kind of like jogging on a treadmill where you have to keep your feet moving to stay in place.

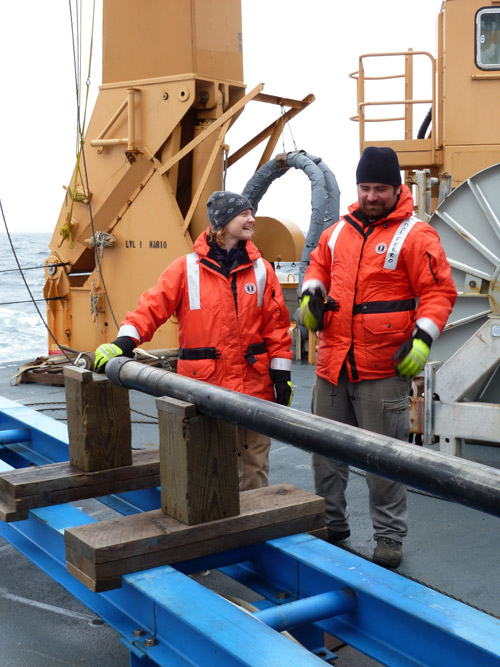

The first type of coring process we tried was also the simplest. Called gravity coring, it is essentially just sticking a big tube into the sea floor and pulling it back up to the ship. While the concept is simple, the process of obtaining a core from nearly two miles deep involves a lot of specialized equipment, expertise, and technique. We have two United States Geological Survey marine technicians aboard this cruise mainly to run the coring operations. Pete DalFerro and Jenny White run the coring show up until the core samples are back on deck and then they start preparing the gear again for another run.

USGS Marine Technicians Jenny White & Pete DalFerro getting the gravity core rig ready for deployment in the southern Beaufort Sea.

USGS Marine Technicians Jenny White & Pete DalFerro getting the gravity core rig ready for deployment in the southern Beaufort Sea.

The gravity core consists of a 2400-lb weight on the top and connections for 10-foot lengths of 4-inch diameter steel tubing. Then a thick clear plastic core liner is slid into the steel tube to facilitate removal and shipping of the cores. For our drop we used one 10-foot length of pipe. A core catcher is placed just inside the tip of the tube. It has a cone formed of upward-tilting flexible steel strips that lets the sample slide up into the tube but keeps the sample from sliding back out the tube on the way back up to the ship. Finally, the rig is finished with the core cutter which is a sharp , thick reinforced tip.

Prior to deployment a core catcher (right) is put in the tip of the steel coring pipe with the flexible fingers pointing up. Then the core cutter (left) is attached to the end of the pipe, completing the coring rig. Samples are taken from both items as they are removed from the coring pipe before the main core is recovered.

Prior to deployment a core catcher (right) is put in the tip of the steel coring pipe with the flexible fingers pointing up. Then the core cutter (left) is attached to the end of the pipe, completing the coring rig. Samples are taken from both items as they are removed from the coring pipe before the main core is recovered.

The coring rig sits on a custom rail system bolted to the rear working deck (called the fantail.) When it is time to roll, a rope is connected to a capstan via pulleys to pull the coring gear to the stern. Then a thick steel cable running through a block (pulley) on the stern a-frame is connected and the ship's main winch pulls the corer upright and out of the 'bucket' that holds it steady on deck. The signal is given and the gravity corer starts its way down to the bottom.

The gravity core rig on its deployment rail, ready to be tipped up and lowered overboard to the sea floor. The heavy weight on the near end weighs 2400 lbs and the 4 inch steel pipe is 10 feet long.

The gravity core rig on its deployment rail, ready to be tipped up and lowered overboard to the sea floor. The heavy weight on the near end weighs 2400 lbs and the 4 inch steel pipe is 10 feet long.

The progress of the operation can be monitored by watching a winch computer screen that measures the tension on the winch and how much wire is played out. As it neared the bottom the winch payed out wire at its maximum rate of 100 meters per second. We could tell when the sampler stopped because the tension on the wire suddenly lowered by about 2000 lbs. as the weight of the rig was resting on the bottom instead of the wire. Then it was all winched back up and brought back on deck.

The winch display pre-sample, showing about 5500 lbs of tension and 2335 meters of wire out.

The winch display pre-sample, showing about 5500 lbs of tension and 2335 meters of wire out.

Once on the sea floor, the winch display shows about 3500 lbs of tension as the weight of the coring gear is resting on bottom.

Once on the sea floor, the winch display shows about 3500 lbs of tension as the weight of the coring gear is resting on bottom.

Then the geologists take over, scraping samples from the outside of the metal core tube and taking samples from the core cutter and core catcher as they are removed. Then the plastic liner is slid out, wiped down, and measured for cutting into manageable lengths. After trimming to size, plastic caps are taped on each end and samples are meticulously labeled, with every step annotated on a core data sheet. Finally, the samples are brought to a big walk-in refrigerator in the lab where they will be kept until they are offloaded in Seattle when the Healy returns to its home port.

Brian Edwards and Andy Stevenson recovering samples from the core cutter and core catcher before removing the plastic lining holding the main core sample.

Brian Edwards and Andy Stevenson recovering samples from the core cutter and core catcher before removing the plastic lining holding the main core sample.

Cruise Chief Scientist Brian Edwards prepares to label a core sample in clear tubing that has been trimmed to a manageable length, capped, and brought into the lab.

Cruise Chief Scientist Brian Edwards prepares to label a core sample in clear tubing that has been trimmed to a manageable length, capped, and brought into the lab.

SPECIAL FEATURE:

Why does the cable tension increase as the coring rig gets deeper in the water?

Which part of the core sample is older, the top or the bottom?

That's all for now! Best- Bill