Speed 0* knots (kts) (*backing and ramming through thick ice.) Course 123 Location Northern Canada Basin, 82.27° N, 135.51° N Depth 3637 meters.

SPECIAL FEATURE DISCUSSION:

(see previous journal for the questions.)

Polar Bears can eat snow or ice to get fresh water. Even sea ice becomes fresh over time as tiny pockets of unfrozen brine work their way down and out of the ice.

We are very far north now where longitude lines are getting pretty close together, so our longitude changes fast when we are moving. Across the globe, latitude lines are parallel and always the same distance apart while longitude lines converge at the poles.

TODAY'S JOURNAL:

Good news- the Louis successfully repaired their propeller shaft bearing and we met up with them last night. Our rendezvous point will be the farthest north we get on this cruise at about 82.5° latitude. There were hopes of perhaps going as far as 85° this year but we are starting back southeast in order to map other priority areas and return to Barrow in time for our 6 September offload. I'm tickled to have made it so far north in the world!

To continue yesterday's story, after using our subbottom profiler and multibeam sonar to map more of the so-called '09 Seamount a sampling site was selected. The ship was positioned so that there was a patch of open water at the stern where the piston coring rig would be rigged and lowered (look back at the 13 August journal entry for details of the piston coring process.) We were in over 3000 meters of water (nearly 2 miles), and the round trip for the coring rig down to the sea floor and back to the deck took about 2 hours. While we were waiting the ship kept itself nudged into ice ahead, keeping the stern in the opening as we were working on the fantail (lowest & aft most deck.)

Our 2400-lb piston-coring rig on deck, ready to deploy. Note the heavy weight in the blue holding bracket (aka the 'bucket'), the trigger mechanism and tripping arm, and loop of slack cable that will uncoil as the coring rig free-falls the last several meters to the sea floor when the trigger deploys.

Our 2400-lb piston-coring rig on deck, ready to deploy. Note the heavy weight in the blue holding bracket (aka the 'bucket'), the trigger mechanism and tripping arm, and loop of slack cable that will uncoil as the coring rig free-falls the last several meters to the sea floor when the trigger deploys.

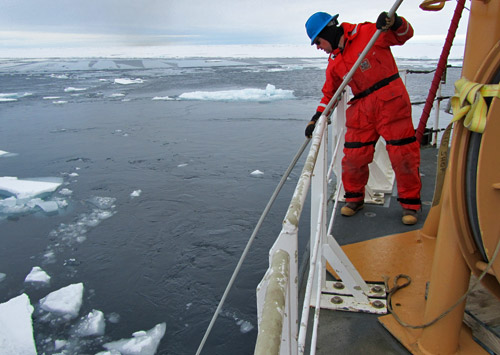

Blocks of ice would come drifting back through our open lead and we used long ice poles to push the pieces of ice away from the stern where our winch cable was lowering and raising the coring gear. An ice pole is made of aluminum and about 20 feet long with a sharp hook and point at the end. Some ice pieces were pretty big (maybe 15 feet wide and several feet thick) but there were three of us with ice poles and if we shoved them long and hard enough we could divert their paths from our cable.

Bill wielding an ice pole to push off loose blocks of ice threatening to interfere with coring operations. Photo by Helen Gibbons.

Bill wielding an ice pole to push off loose blocks of ice threatening to interfere with coring operations. Photo by Helen Gibbons.

We also had an audience during the operation. A ringed seal was in the open water swimming around for a while, probably wondering what we were and why we were in its territory!

A ringed seal watched our coring operation from the open water astern of Healy for a while, no doubt wondering what we were doing there.

A ringed seal watched our coring operation from the open water astern of Healy for a while, no doubt wondering what we were doing there.

The coring operation was successful, returning over 4 meters of sediment from the sea floor. The bottom 3/4 of a meter or so was a neat orange-colored mud with the rest a medium-brown mud. The core liner got stuck a little in the core pipe but our marine technicians Pete DalFerro and Jenny White were able to separate the bottom core pipe and twist it enough to expose the core liner for cutting in the middle. Then they used a long punch-out tool to push the lower half of the liner out of the bottom core pipe section far enough to get a grip on it and pull it out. I filmed the process from beginning to end and finished with a nice edited 20-minute video of the operation.

We were happy to see a muddy piston core return from its nearly 4-mile round trip to the sea floor and back. The mud far up its sides indicated that we got good penetration, as did the 9500-lb pull needed to get the coring rig out of the muddy bottom suction and on its way back.

We were happy to see a muddy piston core return from its nearly 4-mile round trip to the sea floor and back. The mud far up its sides indicated that we got good penetration, as did the 9500-lb pull needed to get the coring rig out of the muddy bottom suction and on its way back.

Such recoveries are important so geologists and oceanographers can compare their interpretations of subbottom profiler and multibeam bathymetry data with real samples. They also have a battery of tests and measurements to perform on the core samples at the lab back home. Cores are split lengthwise with parts being used for study and other portions set aside in core libraries for future reference or research. For now the trimmed, capped, and sealed sections are resting in a big wooden box known as 'the coffin' in a walk-in refrigerator in the science lab. They will be offloaded a few months from now in Seattle and then trucked back to the USGS in Menlo Park, California.

SPECIAL FEATURE:

What is a seamount?

While we were stopped in the ice, our GPS indicated that we were moving at about 0.5 knots. I was out on the fantail from 8:00 am to 1:30 pm and would swear that we didn't move. Can you explain this discrepancy?

That's all for now! Best- Bill