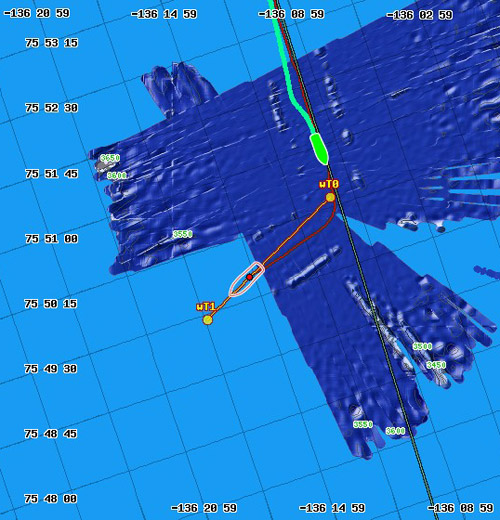

Speed 4 knots (kts) Course 180° Location Canada Basin, 75.91° N, 136.15° W Depth 3560 meters

SPECIAL FEATURE DISCUSSION:

(see previous journal for the questions.)

I can think of two likely mechanisms to move fairly large sediment like pebbles far offshore. Normal deposition quickly drops out coarse material like pebbles at or near shore, with no chance of them drifting far from land. But enormous mass wasting events known as turbidity currents (kind of like giant underwater landslides) can move sediment vast distances as they pick up speed down steep continental slopes and spread out over abyssal plains. However, a classic turbidity current-derived deposit shows graded bedding with the most coarse debris settling out first, followed by ever finer sediment in an upward direction within the layer. A casual look at our core sample didn't show this, though as a disclaimer I'll say that a later careful look in the lab may contradict this hasty conclusion of mine.

The other way I can think of to bring pebble or larger-sized sediment far into deep Arctic Ocean waters is ice rafting. Since ice floats and drifts, sediment caught in Arctic ice can travel long distances before it is dropped as the ice eventually melts. Sediment-laden ice can originate in glaciers on land, or as sea ice freezes fast to shore and later gets liberated by spring tides or offshore winds. Perhaps the more rounded bits in my sample were from pebble beaches and rafted on such shore ice to the deep water. I suspect that most of the pebbles, with their more jagged texture, came from glacial ice. Glaciers are extremely efficient at physically weathering rock, grinding and pulverizing it under their relentless pressure and steady movement down slope. If the pieces don't later get a polishing ride in a river or stream their edges can stay quite sharp. If glaciers reach the ocean and deep enough water the distal ice will begin to float and break off pieces (sometimes incredibly large) that become drifting icebergs in a process known as calving. These icebergs can persist for years, slowly showering the sea floor with their sediment load as they drift and melt. So if my pebbles indeed were ice rafted they could have originated far inland nearly anywhere around the Arctic Basin, potentially riding from Europe, Asia, Greenland, North America, or some smaller Arctic Island to their resting spot in the Canada Basin.

TODAY'S JOURNAL:

The ship is pretty quiet today as we are on a Holiday Routine for Labor Day. Monday will be hectic for the crew, getting our team off the ship and bringing on the next science team at Barrow. So today is the day we observe Labor Day on board. Still, there is always work to be done and crew members needed to stand watch around the clock. One important task today for our science team is to begin packing up all of the gear that we've been using. One interesting process I watched for a while this morning was the task of dismantling, moving, and stowing the heavy pieces of the coring rig track. The next cruise is deploying moorings (instruments anchored to the sea floor that collect various types of data), so they need the fantail cleared for their operations. Our marine techs and the MSTs took the rail apart and moved it to the starboard side with one of the fantail cranes where it will wait until the Healy returns to home port in Seattle in October. Then Jenny will drive a USGS truck up from California to pick everything up and bring it home.

The starboard fantail crane lifts a section of the coring rig track to be stowed out of the way until the Healy returns to its home port of Seattle where it can be offloaded onto a truck.

The starboard fantail crane lifts a section of the coring rig track to be stowed out of the way until the Healy returns to its home port of Seattle where it can be offloaded onto a truck.

Peering out from aftcon I could watch the MSTs stowing sections of the coring rig track along the starboard rail, out of the way for the next science team.

Peering out from aftcon I could watch the MSTs stowing sections of the coring rig track along the starboard rail, out of the way for the next science team.

Yesterday we wrapped up some business, beginning at quarters. When quarters is called every Friday afternoon all hands except those actively working the ship assemble on the flight deck for awards, promotions, news from the captain, etc. Our chief scientist Brian Edwards took the opportunity at quarters to thank the crew for their support of our operations and to give the captain and selected crew members tokens of our appreciation.

Chief Scientist Brian Edwards thanks the Healy's captain and crew for their support of our expedition.

Chief Scientist Brian Edwards thanks the Healy's captain and crew for their support of our expedition.

We also had our last flight opps with the Louis, sending the Canadian delegation we've had on board back over and retrieving the US personnel that were living on the Louis. We're doing a final seismic line until noon today and then breaking off our southern track line to cruise back towards Barrow.

At noon today the captains of both ships exchanged pleasantries over the radio and then we broke off on a SW course, accelerating towards Barrow and our Monday departure operations.

At noon today the captains of both ships exchanged pleasantries over the radio and then we broke off on a SW course, accelerating towards Barrow and our Monday departure operations.

I've been trying to get organized, doing laundry, and packing a box of low-priority, bulky, and heavy stuff to have shipped home later. Hopefully it will make the final packing job easier when that gets rolling tomorrow and Monday. The ice is growing more patchy and we're seeing a lot more open water as we head south. It makes for a really quiet, flat ride when we are usually in open water but there is no swell due to the dampening effect of the remaining ice. Perhaps as we head south we'll see more birds and whales- at least that's what I'm hoping for!

Ever hopeful of another bear, seal, whale, or bird sighting, Bill scans the horizon using the port-side 'big eyes' on the Healy's bridge.

Ever hopeful of another bear, seal, whale, or bird sighting, Bill scans the horizon using the port-side 'big eyes' on the Healy's bridge.

My, what big eyes you have! The Healy sports two pairs of 'big eyes', giant binoculars on heavy stands. One is found on each side of the bridge.

My, what big eyes you have! The Healy sports two pairs of 'big eyes', giant binoculars on heavy stands. One is found on each side of the bridge.

SPECIAL FEATURE:

Here's a riddle for you: What grows like grass on our railings at night but gets mowed down by Arctic sunlight?

(Props to Sarah for helping me word this riddle!)

That's all for now! Best- Bill