We are now two days into collecting our data and I thought that I would spend some time explaining why we are here.

Our testing site is along the northern coast of Unimak Island, Eastern Aleutians in an area known as the “slime bank”. So named by fishermen on account of the abundance of jellyfish. It was first reported by Lieutenant-Commander Zera Luther Tanner U.S.N who commanded the fish commission steamer, Albatross, in Alaskan waters 1888 to 1893. We stop at various points and collect information. It takes roughly two hours to do this at each station and we complete about seven stations a day on a 24 hour rotation.

We collect four pieces of data at each stop we make along the Aleutian Peninsula.

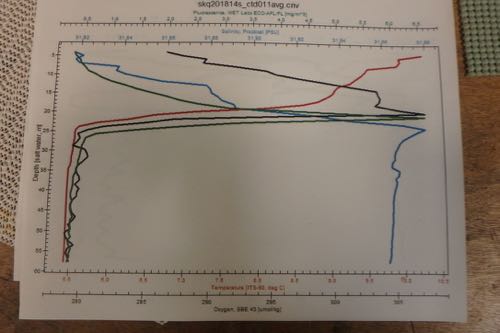

The CTD collects data on the physical properties of the water. The equipment collects information on the temperature and salinity of the water. It measures the oxygen level and records the fluorescence. This is all done over different depths so we can see the conditions in the water column. This allows the scientists to see what conditions the specimens are living in.

The next piece of equipment in the water is the Arcis sonar. This also looks at the water column. The purpose of the sonar is to see into the water column horizontally to see the big jellies in the area so we can get a count of them. It also shows where they are in the located in the water column. It also allows us to see other organisms like fish so we can examine the predator prey relationship.

Sample of plot data from the CTD.

Sample of plot data from the CTD.

We then do a plankton tow. Reasons for doing a plankton tow are to see what organisms are in the sea at any given time and to see if their abundance varies by season and from year to year. We have two levels of nets. The small bongo nets consist of two 20 cm plankton ring nets mounted side by side with a small mesh width and a long funnel shape. Both nets are enclosed by a cod end that is used for collecting plankton. We also tow a 1 meter ring net below this, of a different mesh width, to collect larger samples. Once collected, the jelly specimens are sorted by species, measured and sometimes photographed. The large samples are returned to the ocean and the rest of the contents are preserved for the trip home to the lab for further analysis. As we collect specimens, we are finding new species we haven’t seen before on previous trawls. We are also finding plenty of our target species Chrysaora Melanaster which is good!

Sample taken from 1 meter ring net ready for sorting.

Sample taken from 1 meter ring net ready for sorting.

The last piece of equipment to go into the water is the planktonscope. This is towed behind the boat for 90 minutes at a speed of around 2kts. It is constantly put through a cycle of changing depth from the just below the surface to 10 meters above the ocean bottom. This equipment shows the microorganisms in the area that are the food of the jellies. It also shows where they are in the located in the water column. By combining the images of the Arcis and the planktonscope we can see the whole ecosystem.

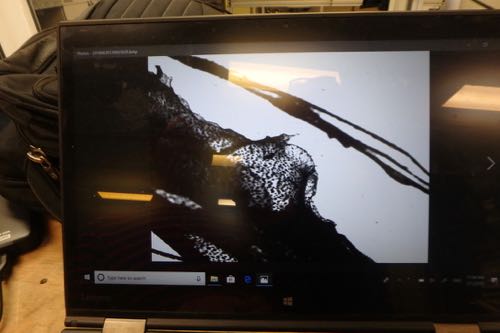

Image of jellyfish tentacle on the planktonscope.

Image of jellyfish tentacle on the planktonscope.

In this project, we want to see where the jellies originate from so we can see how the jelly can respond to different physical environments. The data sets go from copepods, fish larva, and pelagic fish, so the scope of this project is larger. For example, when we are hungry onboard, we know to go to the mess for food. Do the fish in the ocean in this area know where to go for food?

Crew Profile of the day:

Kim Hiene.

Kim Hiene.

Name: Kim Hiene

Position: 2nd Cook

From: Nebraska

How did you end up on the R/V Sikuliaq?: Moved to Florida to escape the cold winters and ended up working on boats. Kim has spent 10 years onboard over 7 different boats. The Sikuliaq is her favorite.

What are the best and worst parts of your job?: Kim enjoys the freedom to cook and bake anything she wants. The idea of being able to travel and cook is a big draw. The downside is that she only knows how to cook for large groups!

Kim is an amazing chef! The food has been delicious!

Add new comment