The many hues of blue and grey meet over the Bering Sea.

The many hues of blue and grey meet over the Bering Sea.

Morning was a Rothko painting, the subtle blues of the sky forming the horizon with the pewter grey of the sea. The sea had calmed compared to the past few days and I could see farther than ever before, or so I thought.

To find out just how far away out the horizon is, I went upstairs to the bridge, which is the control center. There I learned about the horizon from Chief Mate Don Heffern and Second Mate Jeremy Fox.

Chief Mate Don Heffern (left) and Second Mate Jeremy Fox (right) explain the controls in the bridge.

Chief Mate Don Heffern (left) and Second Mate Jeremy Fox (right) explain the controls in the bridge.

Both Don and Jeremy answered my questions about the various computer screens and listened politely as I expressed my disappointment that the ship was not steered using a giant wooden wheel. There are buttons to press for the rudder to change direction and a lever for thrust. At least Don had some sea shanties stored on his phone.

As we stood in the bridge on the top deck, I asked how far the horizon was. "Which one?" Don asked. What? There are more than one horizon? As Don explained it, the visible horizon is based on the curvature of Earth only and there's a way to calculate how far it is. The formula is 1.7 multiplied by the square root of the height of your eyes.

The radar horizon is farther than the visible horizon because the radar waves can travel around the earth. And yes, there's a formula for that. It is 1.21 multiplied by the square root of the height of the radar antenna. Both Don and Jeremy said that other factors come into play when travelling in high latitudes. Mountains and ships can appear inverted because of the angle at which light is traveling through the atmosphere. These are called "polar mirages". Because polar regions only experience indirect sunlight, images might appear distorted or upside down to our eyes. Seeing is not always believing in these latitudes!

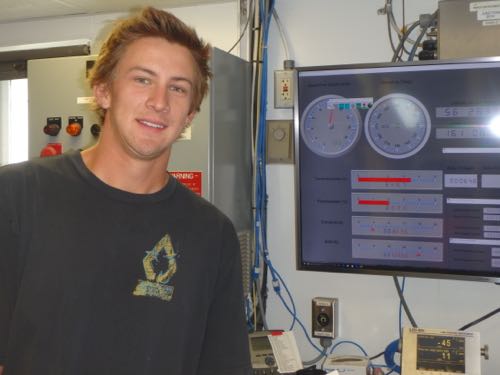

Polar Profile: Brandon D'Andrea

Brandon D'Andrea, the Oceanus Marine Technician, talks about how he became a marine technician.

Brandon D'Andrea, the Oceanus Marine Technician, talks about how he became a marine technician.

Brandon is the marine technician on the Oceanus. When he was an undergraduate student at the University of Hawaii, he sailed with the science club. This allowed him to understand what a marine technician does and he decided that it was a perfect fit for him. He was in the MATE (Marine Advanced Technical Experience) Program for two months, during which he shadowed marine technicians. Now he is working full-time as a marine technician at Oregon State University and loves what he is doing.

Add new comment