**8 AM: ** Today is probably our last day of complete free time. Tomorrow morning we will pack up all of our gear and clean the apartment, so that we are ready to be picked up to go to the ship in Korsakov by 10 am. Since we are all typically up by 6:30 am, this will not be a problem to do in the morning. That makes today a day of our own choosing. Most likely we will spend our time playing more games (Blockus, Set, Golf, and … hmm, apparently we might need to either buy some more games or break out the cribbage board), reorganizing the coolers that are holding the gear and … biding our time.

So while we have this "lull in the activity” I will take the opportunity to tell you about some of the discussions that Ben and I have had concerning the archaeology questions that the group will be working on this summer.

One of the questions has to do with determining when people lived in the Kuril Islands. When we look at the radiocarbon data from last year’s expedition and combine it with dates from other research sources, we find that there are two discontinuities or gaps in the occupation sequence of the Kuril Islands. That is, that there are no radiocarbon samples with dates in certain ranges.

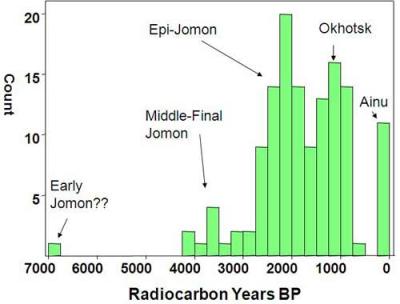

One of these gaps is about 300-500 years ago, the same time as the "Little Ice Age”. The "Little Ice Age” occurred at the same time as the Middle Ages in Europe and was a prolonged period of colder than average global temperature. It is called the Little Ice Age because it was not as significant as the last geologic ice age, where much of the Northern Hemisphere was covered with glaciers, but still had significant economic and cultural impacts. (See graph below.)

Radiocarbon Dating

Radiocarbon Dating

This graph shows the number of radiocarbon samples from the Kuril Islands that fall into different age ranges. Different occupational groups are indicated – note the gap between about 300-500 years ago with no samples. What is the cause of this gap? That is one of the questions that we will try to gather samples to answer this summer. (Graph courtesy of Ben Fitzhugh)

Gaps in data like this could indicate that people did not actually live in the area during that time, that we have just not found the evidence that they lived there or that there is no evidence to find – i.e., that nothing was left behind or preserved. So when there is a lack of evidence like this, archaeologists cannot simply assume that people didn’t live there, they would like to find some other information that supports their hypotheses. So in this case, if our hypothesis is that during the Little Ice Age the Kuril Islands were getting too cold or stormy and people moved away, how could we determine this? What kind of evidence would we look for in the artifacts immediately above and/or below that time period? This is one of the major questions that we will be trying to address this summer by collecting additional samples, particularly radiocarbon samples at sites where there were long occupational histories, like Vodopadnaya on Simushir and Drobnyye on Shiashkotan.

The other interesting pattern in the radiocarbon data is shown when the dates are arranged by island. (See graph below.)

Dates by Island

Dates by Island

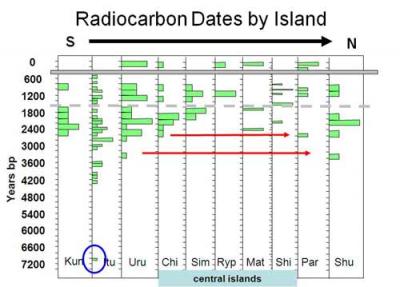

In this graph the radiocarbon dates are arranged by the island on which the sample was taken and the time period of the sample. The islands are organized with the southernmost islands to the left and northernmost to the right. Note the "hourglass” shape of the data with earlier occupational periods on both ends of the island chain. Why is there no evidence of similar occupations in the central islands? That is another of the questions that we will try to address this summer. (Graph courtesy of Ben Fitzhugh)

The northernmost and southernmost islands have earlier occupational time periods than the central islands. Kunashir (Kun), Iturup (Itu) and Urup (Uru), the three southernmost islands, have occupational periods that go back to nearly 5000 years ago, while Paramushir (Par) and Shumshu (Shu), the two northernmost islands, have occupational periods back to about 3500 years ago. It is interesting that the Central Islands, however, Chirip (Chi) to Shiashkotan (Shi), only have data indicating occupational periods back to about 2500 years ago. Again, this could mean that people did not live on the islands during that time period, or that they did live there, but there was nothing left behind or the artifacts were not preserved, or it could mean simply that we have not yet found the evidence that they did leave behind.

When we excavated test pits last year on these islands, particularly the two that we will revisit this year, Simushir and Shiashkotan, we did not have enough time to "get to the bottom” – which means that we were still uncovering artifacts at 1 meter below the surface when we had to fill the holes back in at the end of the day – so it is quite possible that we just have not uncovered the older material, yet. So the big question is whether the missing dates indicate an actual situation – there really weren’t people there earlier than 2500 years ago – or are the result of a sampling inconsistency issue – have we just not found the evidence of people there? This is an especially important question because it will help us to form a conclusion about whether people migrated into the islands from the south to the north, hopping from island to island, or from each end, but at different time periods and eventually "filled in” to the middle.

The Kuril Biocomplexity Project is the combination of several scientific disciplines, including geology, archaeology, zooarchaeology, volcanology and paleoclimatology, and each of these disciplines has specific interests and questions that they are trying to address in each of the three field seasons. But all of the questions and research sampling are also geared toward the larger goal of understanding when and how the people and animals adjusted to, impacted and lived through changes in their island environment, such as climate or periodic volcanic activity, over the latest part of the Holocene Period (~5000-7500 years ago). As a general scientist myself, it is a fascinating project with which to be involved, because there are always so many different types of things to learn about and so many generous and intelligent professional scientists willing to share their work, ideas and explanations with me.