October 28, 2019 Landed

Latitude 69 degrees 50.7163 minutes North

Longitude 18 degrees 59.5221 minutes East

Air Temperature 0 degrees Celsius

Variable wind, 0-5 knots

Air Pressure 1008.9 millibars

We have returned to Tromso. This morning, we woke up to beautiful views of snowy mountains and fjords. People stood on deck with coffee and tea, waiting eagerly for our arrival on land.

As we neared Tromso, snow began to fly. Our view of the city was obscured by the storm as we pulled up to the dock.

As we neared Tromso, snow began to fly. Our view of the city was obscured by the storm as we pulled up to the dock.

Thick blowing snow greeted us as the Fedorov pulled up to the dock. Soon after, the storm passed over. Now the snowy ground is sparkling in the sunlight and the treed hills of Tromso are calling me for a hike. It is fun to gather at the rails with these new friends, but also bittersweet. I felt sad to say goodbye. However, now that we've gone through the rituals and farewells, I am antsy to get off the boat.

But not yet. We are waiting to be officially cleared through customs before we can leave the port area. We have been able to step foot off the ship to unload some gear. I took the opportunity to take a mini-walk. It was exciting to walk farther than the length of the ship in any one direction. But soon I came to a fence around the port and had to turn around. Now, we are sitting and waiting.

I was able to step off the ship for a few minutes and photograph this view of the Fedorov from shore.

I was able to step off the ship for a few minutes and photograph this view of the Fedorov from shore.

It is hard to be patient. We've been mostly confined to this ship for over 5 weeks. There were brief excursions onto the sea ice when we were setting up the equipment. However, we weren't able to wander at all due to polar bears and the risk of thin or breaking ice. I am ready to go for a run, to hike through the woods, to be able to go wherever I want to. But not quite yet.

I want so much to be in the forest, to tromp through snowy bog, to walk on the beach. These emotions help me to remember that so many people have a connection, a relationship with this land. There is a diversity of stories and histories with this place.

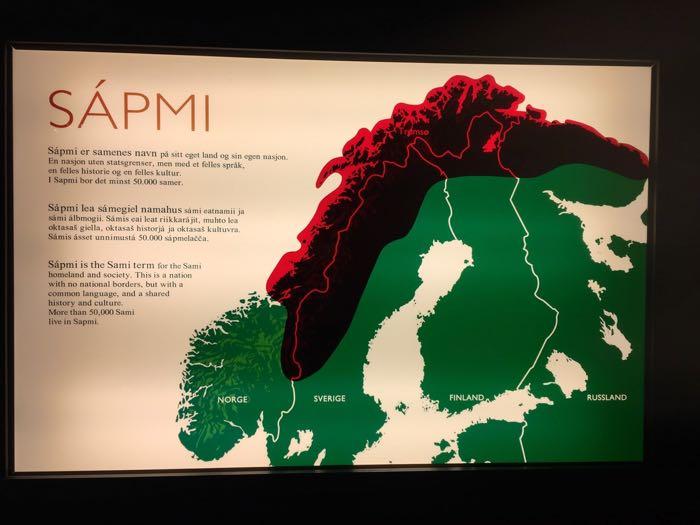

This area is Sapmi -- the land of the Sami people. Throughout the northern areas of what is now known as Norway, Finland, Sweden, and Eastern Russia, Sami people have lived for generation upon generation. For them, this part of the Arctic is home. It is the land their ancestors cared for and relied upon.

This map, from the UiT Tromso Museum depicts the Sapmi, the land of the Sami peoples.

This map, from the UiT Tromso Museum depicts the Sapmi, the land of the Sami peoples.

Many people do not know about the Sami; those that do, usually think of the culture in terms of reindeer herding and the traditional dress of the Sami. This is in large part due to decades of forced assimilation and discrimination. But Sami people fought back against this, claiming not only a Sami identity but one that is nuanced and complex.

Sami lifeways and realities are varied and dynamic. There are at least 5 main dialects of the Sami language; these dialects demonstrate both differences and similarities across groups of Sami. In the past, some lived inland, where herding reindeer is common; others lived along the coast and relied more upon the sea for food. Now, Sami live out on the land, in small towns, and in urban centers like Oslo. Some have moved far beyond the Arctic, living all over the world. But many Sami people continue to live in the Arctic.

The Sami Council is one organization that works to sustain this Arctic home and the Sami people. They often join with other Indigenous peoples of the Arctic to address pressing problems and exciting opportunities.

The Sami are the largest and most well-known group of Indigenous peoples in this region, but not the only. There are also many, many Indigenous peoples in Russia; RAIPON is an organization that was created to represent them. There is another group of people recognized as a minority group in Norway. They are called Kven or Kainu, and there is an ongoing conversation among Kvens about their history on the land and possible identity as Indigenous people. The Norwegian Kven Association is likely a good resource for more information, but their website is only in Norwegian or Kven.

In a seascape of stark sea ice, it is easy to forget that the Arctic is the homelands of many Indigenous peoples. They have lived here since time immemorial; their cultures and languages reflect this intimate relationship with place. In a recent address to the Arctic Council, Saami Council president Ms Åsa Larsson Blind stated:

"The [UN International Year of Indigenous Languages] provides a unique opportunity for the Arctic Council to prioritize the indigenous languages. Our indigenous knowledge and languages are inextricably linked, both holding valuable knowledge, lessons learnt, and know-hows related to biodiversity, climate change adaptation and resilience. The environment to which the indigenous languages apply are changing dramatically. We know that the Arctic indigenous knowledge and the inherent indigenous languages holds insights to address these changes, to adapt and to identify potential solutions that could benefit us all."

Though 2019 is coming to a close, the push for recognizing and sustaining Indigenous languages and Indigenous Knowledge should not fade away. As I return home, I am committed to finding positive ways that I can engage in efforts to recognize and sustain Indigenous languages. At the very least, I have 6 weeks of Sugts'stun words to catch up on. Sugpiaq-Alutiiq language bearers share the Sugs'tun Word of the Week on the local radio station KBBI in Homer, Alaska.

Being here in Sami homelands, I have tried to learn more about their history, culture, and contemporary experience. However, I know only very little. There are some resources I can point you to though. First, I would suggest a visit to the Saami Council website. The UiT Museum of Tromso is also a great resource. They have a physical and webexhibit on the Sami movement to become a nation, which I thought was very insightful and well done.

Word of the Day In the Sami dialect spoken most commonly in this part of Norway, vahca describes new snow. Here is a fascinating academic paper on terms for snow used especially by Sami reindeer herders.

Education Extension Wherever you live, there are almost always histories of Indigenous peoples with a relationship, culture, and language specific to that place. Take some time to learn more about this, and seek out cultural centers or knowledge-bearers. There are many books and other great resources to use with children and teens. Look especially for books and resources authored by Indigenous people themselves.

In the part of Alaska where I live, Chugachmiut Heritage Kits are a unique and truly incredible compilation of stories, videos, photos, drawings, activities, field trips, and lessons around sustaining Sugpiaq-Alutiiq and Eyak culture. The digital resources for these kits were brought together by local education coordinators across the Chugachmiut villages. I highly recommend the Heritage Kits - both as a way to learn more and a rich, engaging resource for educators.

To learn more generally about Indigenous peoples in the Arctic, you might check out the following two books for young children:

An Inuksuk Means Welcome by Mary Wallace introduces young readers to some basic words in Inuktitut (Inuit language) and explains how Inuit people use inuksuit to navigate and communicate in Arctic environments.

Whale Snow by Debbie Dahl Edward and illustrated by Annie Patterson tells the story of young Amiqqaq as he learns about his family's traditions around whale hunting and the concept of the happiness whales bring to them. It is a beautiful story with equally wonderful images and includes a number of Inupiaq words. According to the book, you can even read the full story in Inupiaq at the Charles Bridge website; I haven't followed this link myself so I don't know how easy it is to actually find on their website.

Add new comment