When I was chosen as a PolarTREC teacher to work with OASIS in Barrow, Alaska my brother asked, "Why would a self-professed cold wimp like you volunteer to work in the Arctic in the early spring?" As I thought about it, the answer was much deeper than the temporary insanity that my family thought I was experiencing.

Sunset from my laboratory window in BARC at 8:00 PM ADT.

Sunset from my laboratory window in BARC at 8:00 PM ADT.

As a teacher I strive to inspire my students. I challenge them to do their best and take pride in their work. There are many opportunities that are available to them now and in the future to explore, appreciate and protect the world. Once they realize that their actions have consequences, they have unknowingly become environmental stewards. Becoming a PolarTREC teacher was an opportunity for me, my students, and my community to explore, appreciate and protect the world. With this goal in mind, and the possibility of frostbite put aside, I set out on my dream of working with scientists as part of the International Polar Year.

Near the end of my expedition, I left my students an assignment to reflect upon "our" Arctic experience. They had experienced Fairbanks and Barrow through my blogs for almost a month of their school year. I required them to reflect on what they learned about Alaska, the Arctic and science. They asked questions about things they still wanted to know. Lastly, they considered if they wanted to be a scientist that does field work. In the spirit of their reflection, I will follow a similar format in my reflection.

Students digging for earthworms at Ipalook Elementary Science Night.

Students digging for earthworms at Ipalook Elementary Science Night.

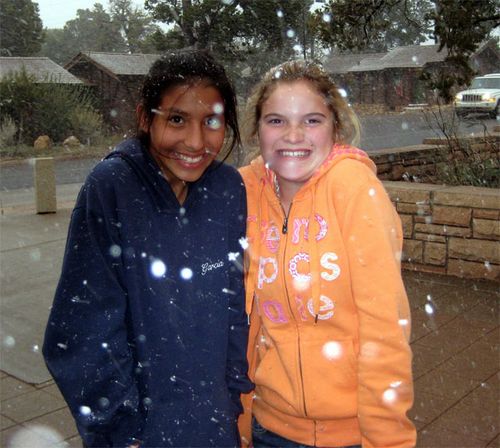

The Arctic and Arizona have much more than the first few letters of the words in common. There is a kindred spirit that lies within the people of these places. It became more obvious to me as I shared my students' ideas and thoughts about living in Arizona with 7th grade students in Barrow. Both sets of students liked the openness and beauty of the land around them. The students both traveled to school by bus, car and walking. The only difference was that bicycles were used in Tucson in place of the snow machines that some students used in Barrow. Tucson students enjoyed the heat of the desert, and as "polar" opposites would suggest, Barrow students enjoyed the cold of the tundra. However, students also delight in unique experiences. The students at Fred Ipalook Elementary school loved playing with earthworms in a tub of soil at Science Night. My students were thrilled to play in the snow on a recent field trip to the Grand Canyon. True Arizonans and Alaskans thrive on the temperature extremes of their region, and leave other people wondering about the "normalcy" of their lives and activities.

Amalia Garcia (l) and Delaney Stephens (r) enjoying snow at the Grand Canyon.

Amalia Garcia (l) and Delaney Stephens (r) enjoying snow at the Grand Canyon.

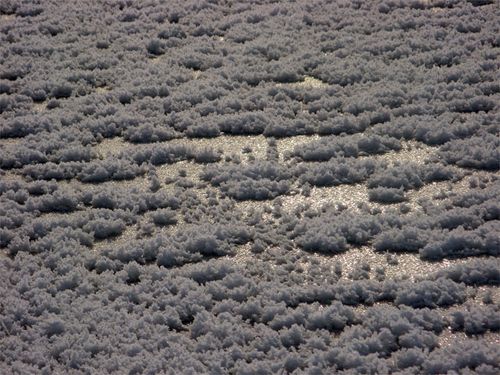

While in the Arctic, I learned that there are many different types of frozen "white stuff". Hoar frost, diamond dust, ice fog, frost flowers, land fast ice, sea ice, pack ice, nilas, permafrost and snow were all foreign concepts to a 5th generation Arizonan desert native like me. I could count on one hand the number of times it snowed and stayed on the ground in Tucson in the 40+ years I have lived here. Ice occasionally forms here on top of dog water dishes and puddles. I was amazed when I was able to start recognizing and differentiating between ice fog and diamond dust. It was fun to sample and analyze the different depths of the snow. I will always remember the echoing sound of my boot as a walked across the frozen snowpack on the tundra, and will continue to search for a better way to describe it to fellow desert rats like myself.

Nilas sea ice glistening among the frost flowers.

Nilas sea ice glistening among the frost flowers.

As with most topics in science, my OASIS experience leaves me with a great need to learn more. I guess I'm not alone, since the scientists with OASIS are doing just that; learning more. There were over 27 projects that occurred during this campaign.

The town of Barrow, AK from the airplane.

The town of Barrow, AK from the airplane.

Barrow, Alaska is only accessible to most travelers by airplane during the winter and spring. Despite the remoteness, the Arctic receives many atmospheric pollutants from the rest of the world. Arctic haze was first noticed in 1750 at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Dr. Glenn Shaw brought his ideas on this phenomenon of atmospheric pollution to the scientific community in 1972. OASIS scientists looked at the chemical and physical fluxes between the Ocean, Atmosphere, Sea Ice and Snow. Many of the projects looked at the life cycles and exchanges of the atmospheric pollutants that are present in the Arctic. As the sun returns to the Arctic in the late winter and early spring it triggers some very complex chemical reactions among all of the mediums and pollutants. Scientists were studying concentrations of mercury and surface ozone and changes in these as they go through depletion events. A list of the chemicals measured and studied sounds like a reading assignment in the CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics: NOx, H2O2, HONO, BrO, POP's, VOC's, halogens, aldehydes, formaldehyde, HULIS, PAN's, organic and inorganic peroxy radicals. Meteorology measurements also played an important role in this project.

Betsy Wilkening sampling snow on a grey windy day near BARC.

Betsy Wilkening sampling snow on a grey windy day near BARC.

Harry Beine explained to me that snow is the key to studying all of the chemistry that is occurring in the Arctic. Snow can act as a transfer mechanism for many of the chemicals. Some are soluble and others are not. Snow contains a lot of surface area for which chemical reactions to occur. Sunlight penetrating into the snow affects these reactions. Concentrations of trace chemicals in the snow, physical properties of the snow, and reflectivity of snow were all things that were studied in the snow laboratory group that I worked with as part of OASIS. We performed many measurements out in the field and many samples were taken home to be analyzed further. I'm looking forward to seeing the results of our measurements, other scientists' data and the correlations that are made among the different data sets. My next step will be to create lessons out of this information.

Betsy Wilkening (l) & Harry Beine (rt) outfitted in Tyvek suits for sampling snow.

Betsy Wilkening (l) & Harry Beine (rt) outfitted in Tyvek suits for sampling snow.

I asked my students to imagine themselves in the role of field scientists. Some of them pictured themselves in that role, but others decided it would be just too cold for them. I can appreciate their viewpoint, because I too thought the same way. The Arctic is an incredible place. As soon as I arrived in Barrow, Harry started to share his knowledge and love of the area. As we sampled snow, or walked between buildings, Harry would stop and show me some newly formed hoar frost and point out the diamond dust. The other scientists, native guides and members of the community also enriched my knowledge by sharing with me. I am very fortunate to have experienced the Arctic and this is something that I can share with my students. As the OASIS scientists and I discussed at dinner one day, maybe my students will conduct research in the Arctic in the next International Polar Year. Hopefully, they will not wait another 50 years to do so. I received many comments from other middle school teachers at my school about how the Arctic and the science being done in that region have become real to their students. This world of sea ice and frozen tundra are now more familiar to them.

I now consider myself a "Polar Junkie," a term coined in our orientation. My PolarTREC expedition has helped me fulfill a lifelong dream of working in a polar region with scientists. Like most junkies though, I'm left with an insatiable hunger to learn more about the Polar Regions and a yearning to return.