The PolliNation

A few weeks ago, I mentioned that my core family up here got a little larger with the addition of the “Pollinator crew”, or what we now call “the Polli-Nation”: a group of three students from Colorado College, Caroline, Lucy, and Alex. Their work runs adjacent to ours, so most of what they do is very similar to what we do in terms of monitoring warmed vs. control plots, but they have a few added twists focused on the bugs that visit the plants and flowers.

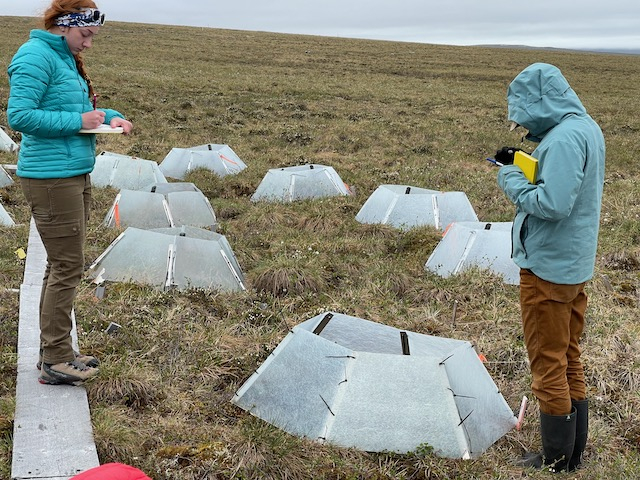

Caroline (L) and Lucy (R) do phenology on the OTCs.

Caroline (L) and Lucy (R) do phenology on the OTCs.

If you’ll notice I said “bugs that visit the plants” instead of “pollinators”, because one of the first things they do at the plots are “visitor watches”–10 minutes of watching for any bugs that come in or out of a plot. Alex told me that it’s a “visitor watch” as opposed to a “pollinator watch” because everything is only visitor until it walks across a flower, and only then can we officially call it a “pollinator”.

Alex conducts a visitor watch.

Alex conducts a visitor watch.

Once it is known to be a pollinator, the group tries to catch it for future analysis. They do this with a variety of tools, the simplest of which is a jar that contains a plaster soaked in ethyl acetate (a chemical which slowly puts the insects to death), which is known as a killing jar. This jar is simply placed over the insect similar to how you might use a cup to carry a spider out of your house.

Alex and Caroline trying to decide which method to use to capture a spider pollinator.

Alex and Caroline trying to decide which method to use to capture a spider pollinator.

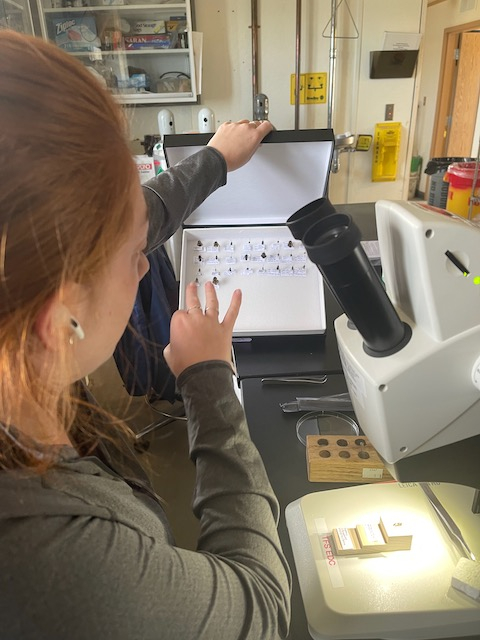

After collecting the insects, they are then labelled and mounted using pins, which can come with some emotional turmoil for those who don't like the idea of harming the bugs. However, once they're pinned and put into a shadow box, they look very pretty!

Caroline walked me through the steps of pinning the bugs and showed me their collection of pollinators so far.

Caroline walked me through the steps of pinning the bugs and showed me their collection of pollinators so far.

Once they are in this state, they can be reviewed by an entomologist to get information down to the species level. They also (very carefully!) collect any pollen grains from the pollinators for future analysis under microscope.

This process of bagging and tagging pollinators is only one portion of the monitoring that the group does. They also regularly take nectar samples (which Caroline tried to teach Jeremy and I how to do and it was really fickle and irritating to do!) and track phenology of the plants.

Caroline taught Jeremy and I to extract nectar, but we sucked at it!

Caroline taught Jeremy and I to extract nectar, but we sucked at it!

I asked the group what they’re researching, and as they all took turns describing the project, Alex ended up summarizing all of it by saying “it’s highly multi-faceted”.

It's funny how "multifaceted" seems to be the perfect description of all science that occurs up here, both within our own project and within everyone else's work. I think this is perhaps a unique aspect of field work, in that... field work is really messy. It's hard to control all the variables in all the ways needed for a more traditional lab experiment, so instead it's about controlling those you can, monitoring those you can't, and collecting all the data to try and make sense of the world around you. In this mess it seems there's no good way to hold a singular focus, but I've come to really enjoy that about the science up here – being able to broaden the scope leaves the door open for so much science to happen in so many different ways.

Add new comment