Our first scuba dive of the expedition is my first in Antarctica, my first under ice, and my first in water this cold. For these reasons, and because some of our gear is new to us, Steve Rupp and Rob Robbins will be accompanying us on a type of test drive called a "check out" dive. As McMurdo Station's diving supervisors, Rob and Steve are ultimately responsible for our team and they need to make sure each of us is as competent and skilled as we claim to be. In the second year of their grant, Amy Moran, Art Woods, Bret Tobalske, and Steven Lane have all been through this once before. Being the new guy, I know Rob and Steve are watching me very carefully. The informal evaluation starts the moment we begin to set up tanks, load up our transports, and climb into our exposure gear. Just getting to the dive site will be a new experience for me.

Diving in 28F/-2C water requires heavy duty exposure protection. A drysuit and insulated undergarment form a system that keeps the wet out and the heat in.

Diving in 28F/-2C water requires heavy duty exposure protection. A drysuit and insulated undergarment form a system that keeps the wet out and the heat in.

One of the environmental challenges facing our team is the 28F/-2C ocean water. To counter the chill, divers wear special suits which keep everything but their heads completely dry. Under the outer waterproof layer, divers wear an insulated "undergarment" very similar to a snow suit, which helps conserve body heat. In the frigid waters of the Ross Sea, this is an absolute necessity. Even standing outside in the Antarctic breeze, a drysuit seems like an appropriate article of clothing. Sweating and struggling to climb into the undergarment and drysuit in the well heated dive locker however, seems more ordeal than adventure. Eventually, I'm zipped into my suit and I run through my mental checklist one last time: Fins, mask, hood, gloves, weights, backpack, tank, regulators; I do not want to be "that guy" who forgot a critical piece of gear before leaving the dive locker. With our 100lbs/45kg each of individual gear loaded and the last member of the research team, Caitlin Shishido, informing us that the transports are warmed up, it's time to head out on the ice. I throw on my "big red" extreme cold weather parka over my drysuit and climb into the waiting transport.

Though a little clumsy on land, the rubber tracks on Pisten Bullys make them ideal vehicles for cross-ice transport.

Though a little clumsy on land, the rubber tracks on Pisten Bullys make them ideal vehicles for cross-ice transport.

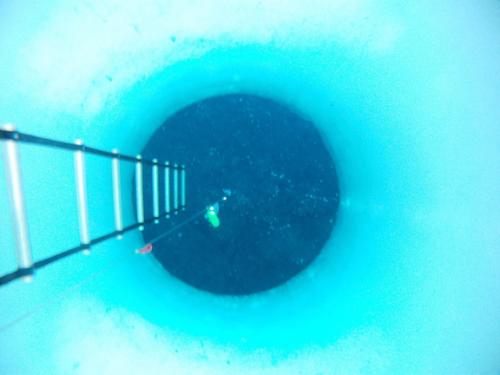

The tracked vehicle's diesel engine roars each time Caitlin's foot depresses the accelerator. Even maxed out at 7mph/11kph, it only takes us ten minutes to reach our dive site at the jetty just below Observation Hill. The previous day, Rob and Steve arranged for the operations team to drill a 4ft/1.3m hole through the ice to give us access to the ocean below. The drill team also positioned a dive "hut" - a shipping container-sized plywood shelter with an access hole in the floor - over the diving hole. Entering the hut, I'm pleasantly surprised: it's warm, light, and spacious and even has a diesel heater stove in one corner. And that's when I see it. Viewed from above, the borehole through 6ft/2m of blue-grey sea ice looks like a portal into another dimension. The water itself is so clear it's almost invisible and dotting the ocean floor below I can make out white objects, though I'm not entirely sure what they are. I don't have much time to think it over; I'm handed a 40lb/18kg weight belt and the unloading process begins in earnest.

The only way below the ice is through one of these 4ft/1.3m diameter boreholes.

The only way below the ice is through one of these 4ft/1.3m diameter boreholes.

Once our individual gear is loaded into the hut, Rob lowers a weighted line into the hole. Every 15ft/5m a loop holds either a checkered flag or a blinking strobe. Like an upside down radio antenna, this will be our beacon home once we're under the ice. Accompanied by Rob, the first group of divers seats themselves at the edge of the hole and slowly straps on their gear. Even for team members with over a hundred Antarctic dives, the process is laborious and clumsy during this first dive of the season. Those of us in the second group help double check clasps, buckles, and hose connections. Following Rob's lead, one by one the divers pivot from their perches at the edge of the hole and drop in. When the last of them go, it's our turn. I sit down on the lip of the plywood floor, attach my weights, backpack and tank, and fins. I double check to make sure the various hoses and buckles are not tangled. Then, I severely restrict my vision, head mobility, hearing ability, and dexterity by putting on my hood, mask, and gloves. The new gloves are a tight squeeze and I need Caitlin's iron grip to force them over my fingers. It's hot and I'm agitated, and I take a moment to calm myself down. In the mean time, Steve Rupp pivots into the hole and descends. Now it's my turn.

Members of Team Pycno (short for "Pycnogonid," the taxonomic class to which sea spiders belong) prepare to dive beneath the ice.

Members of Team Pycno (short for "Pycnogonid," the taxonomic class to which sea spiders belong) prepare to dive beneath the ice.

Comments