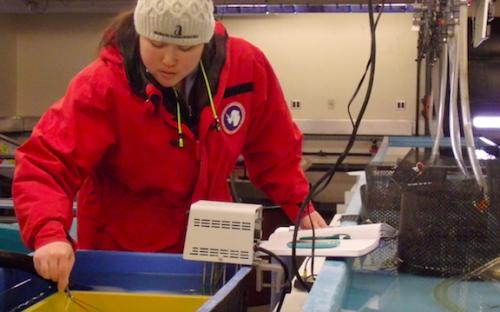

On any given morning in the Crary Laboratory aquarium room, University of Hawaii PhD Candidate Caitlin Shishido can be found looming over the sea tables, staring intently into one particular aquarium, and shifting her gaze every few moments to record something in her notebook. Shishido is performing "pycno flips" as a way of measuring sea spider activity levels under different temperature conditions. Pycno flips are just what they sound like - reaching into the aquarium with a long pair of forceps, she gently flips an animal onto its back, then times how long it takes the creature to work itself upright again. For each sea spider, she'll do this for one hour, flipping it as often as it can right itself. Using a special heating and cooling coil, Shishido varies the temperature in the water to different set points and performs the tests under these variable conditions. As part of a PhD dissertation that is investigating how invertebrates respond to the thermal aspect of their environment, pycno flips are one of the ways she explores the role temperature plays in polar gigantism.

PhD Candidate Caitlin Shishido performing "pycno flips" in the Crary Lab aquarium room.

PhD Candidate Caitlin Shishido performing "pycno flips" in the Crary Lab aquarium room.

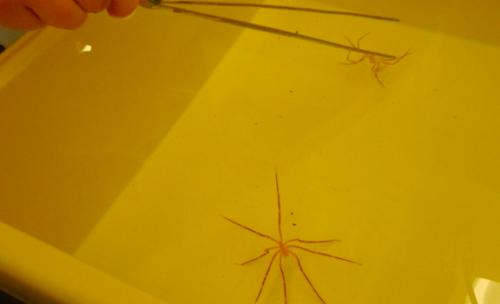

A second part of the oxygen hypothesis for polar gigantism deals with temperature because the metabolic rates of cold blooded animals will increase as water gets warmer. Metabolism ultimately requires oxygen and warm water holds on to less dissolved oxygen - less gas in general - as it warms up. With less oxygen available and more oxygen needed, at a certain temperature large sea spiders may have to limit their activity to conserve oxygen and they won't flip over as quickly or as often. If the oxygen-temperature hypothesis were to hold true, activity levels for large animals would slow down after only a few degrees increase in temperature. Smaller animals would be able to withstand a greater increase in temperature because smaller animals have a lower overall demand for oxygen.

Pycnogonids are flipped over repeatedly for one hour (but are no worse for the wear).

Pycnogonids are flipped over repeatedly for one hour (but are no worse for the wear).

Shishido also performs experiments in an environmental room, one that allows her to vary temperatures while altering oxygen levels in ways similar to the experiments that I'm performing in the room next door. This experimental approach, wherein she alters a few environmental variables, holds all other variables constant, and tracks response rates in the animals, will help Shishido tease apart the relationship between oxygen needs and oxygen availability. It's one important piece of the puzzle in answering the question of why some groups of animals get so large in the polar regions.

By weighing the animals hanging in water, Shishido can determine how much of their bodies are made up of actual tissue and not just water.

By weighing the animals hanging in water, Shishido can determine how much of their bodies are made up of actual tissue and not just water.