Today started out very early. We met for breakfast at 6:30am, drove to the Cantina (Airport Employee cafeteria) and quickly ate our breakfast. We then dropped off two of the members who were at Swiss Camp. They were a couple from Belgium, Alain and Gigi. Next we returned to KISS, where Simon and I had to scramble to get our stuff together as we were the lucky ones to return to Swiss Camp to retrieve the rest of the cargo. We quickly got our gear (I thought we were coming back to KISS, so I did not grab stuff for a full days adventure), and jumped on the ski-equipped twin otter airplane (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_Havilland_Canada_DHC-6_Twin_Otter).The pilots were from Iceland and were very friendly and helpful. They worked just as hard as we did in loading and unloading the plane.

Loading the plane in Kangerlussuaq. L-R Dr. Konrad Steffen, Reggi - Pilot, Nikko Bayou, and Simon Steffen.

Loading the plane in Kangerlussuaq. L-R Dr. Konrad Steffen, Reggi - Pilot, Nikko Bayou, and Simon Steffen.

Air Greenland - Ski-equipped Twin Otter - Cargo area

Air Greenland - Ski-equipped Twin Otter - Cargo area

Air Greenland - Ski-equipped Twin Otter - Seating area

Air Greenland - Ski-equipped Twin Otter - Seating area

Once we were seated, the pilots began their pre-flight checklist and then they proceeded to start the engines. The left engine was the first to start. Then I could see them trying to start the right engine. The prop would spin slowly and stop, slowly and stop. I then heard the engines stop and the pilots shut the plane down. We were not taking off just yet! Quickly, a mechanic was summoned and he immediately dropped the cowl covering the engine, pulled the plugs and tested them. They were glowing red hot, which is good! He replaced the plugs and put the cowl back on. We boarded the plane again and were off! Not sure what happened, but the pilots would not shut the right engine off for the rest of the day.

After the hour delay, we arrived at Swiss Camp around 11:20am. The cargo was staged next to the temporary ski-way. We quickly loaded a snow machine, several used tanks of propane, four empty gas barrels, two large sleds, two large and very heavy batteries, and other miscellaneous items. It took us about an hour to load the plane and tear down the temporary ski-way. Once we got everything loaded (the pilots arranged and secured everything) Simon and I wedged ourselves into the remaining space for the flight home.

Cargo at Swiss Camp - the snow machine is already loaded!

Cargo at Swiss Camp - the snow machine is already loaded!

Ski-equipped Twin Otter at Swiss Camp

Ski-equipped Twin Otter at Swiss Camp

Swiss Camp

Swiss Camp

Cargo area LOADED!

Cargo area LOADED!

Once we got back to Kangerlussuaq, there was a crew from KISS ready to help unload the plane. Koni and Nikko were there as well; ready to start the next phase of flights. Once the Swiss Camp cargo was unloaded, we loaded the Automated Weather Station (AWS) cargo. The AWS cargo consisted of several metal and plastic cases containing spare parts, tools, computers for downloading data and troubleshooting, spare batteries, shovels, traverse food, and an extendable ladder. We all had an emergency pack consisting of a sleeping and camping mat just in case we got stranded on the ice overnight.

Unloading Swiss Camp cargo and loading AWS cargo.

Unloading Swiss Camp cargo and loading AWS cargo.

At approximately 3pm we were off! The first stop was to AWS station NASA-SE. It was located on the eastern portion of the ice sheet, so the flight took about two hours. Once the pilot spotted the AWS, he observed the direction of the wind sensors to determine the best approach. The landing was a little bumpy due to the drifts of snow, but overall it was pretty cool! Once the plane came to a rest, the team jumped into action. Koni and Nikko knew exactly what to bring out and where everything was located. Koni took pictures of the AWS and then wrote some notes to document the current status of the AWS.

Dr. Konrad Steffen taking pictures of the AWS. The pictures will be used to help the team remember what was performed on the AWS.

Dr. Konrad Steffen taking pictures of the AWS. The pictures will be used to help the team remember what was performed on the AWS.

After taking a few pictures, he used the ladder to access the data logger. Within a few minutes, he had successfully downloaded the data and performed a troubleshooting program to verify all the sensors were working. He found two of the snow accumulation sensors (Sonics) were not functioning. He quickly replaced the sensors and then checked to make sure they were functioning.

Dr. Konrad Steffen downloading data from the data logger.

Dr. Konrad Steffen downloading data from the data logger.

His last task was to gather data on the precise location of the AWS. For this, he used a very sophisticated GPS receiver that is accurate up to a centimeter. The reason he needed this data was for the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). His Greenland Climate Network of 18 automated weather stations is now part of the WMO database, used by meteorologist all over the world. His data is being used to improve weather models so that places like the United Kingdom can predict weather more accurately.

Dr. Konrad Steffen - Recording precise GPS coordinates for WMO.

Dr. Konrad Steffen - Recording precise GPS coordinates for WMO.

While Koni was working on the AWS, Nikko and Simon were digging a snow pit nearby to verify the data being collected by the AWS. They started by digging a one meter by one meter hole in the snow, approximately one and half meters deep. The objective is to analyze the last year of snow accumulation. Once the hole was dug, they place a tape measure in the hole and started to record the various layers of snow starting from the top. Each layer had a distinct texture and density, so it was fairly easy to discern each layer as you go deeper in the pit. As they went to the next layer, they recorded the snow texture and shape. Once they analyzed each layer the next step was to record the density of the snow in three-centimeter increments.

Nikko and Simon conducting snow pit analysis.

Nikko and Simon conducting snow pit analysis.

By the time Koni finished repairing the sensors, Nikko and Simon were ready to go. We boarded the plane and were off to the next AWS station, Saddle. Saddle is located south west of NASA-SE, approximately a 30-minute flight. We landed and performed the same procedures as before. The AWS was in good working order, except that snow had accumulated in the data box. Koni had to do a quick download of data and then patch the hole in the back of the box. Once that was completed, we were off to the final AWS, DYE-2.

Dr. Konrad Steffen working on AWS data box.

Dr. Konrad Steffen working on AWS data box.

DYE-2, aka Raven, is the sight of one of the United States military DEW stations. DEW stand for Defense Early Warning. It was part of the cold war of the 70’s and was meant to detect missile attacks from Russia. The US had only a few of these constructed. It is now vacant and slowly being consumed by the ice sheet. At one time this structure stood eight stories high and could be elevated using hydraulic legs.

DYE-2 (Raven) as seen from the plane.

DYE-2 (Raven) as seen from the plane.

DYE-2 needed the same work as the previous stations, download data, dig a snow pit and check for any other issues. We were feeling the cold at this station due to the lower angle of the sun. Koni informed us that the temperature was -18 C. I could feel the cold on my face and had to bundle up. My clothing crackled and the snow squeaked when you walked on it due to the extreme cold. We were happy to finish working at this station. It was 9pm, we were tired and ready to return home. Koni used his satellite phone to order us some pizza. Stan, the KISS manager, picked us up when we arrived at Kangerlussuaq. The pilots joined us for some tasty reheated pizza. I think it was probably some of the best pizza I’ve had in a long time!

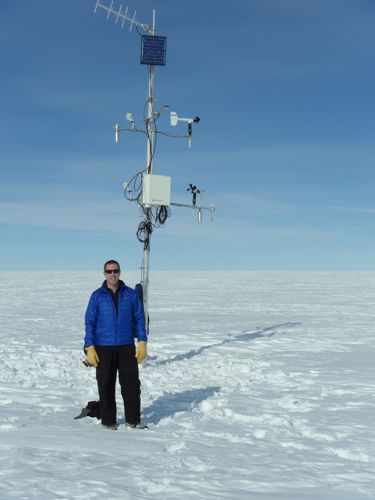

Me standing in front of AWS Saddle, southeast Greenland.

Me standing in front of AWS Saddle, southeast Greenland.

We are flying south to finish the southern traverse, then to the east coast to switch planes. Looks like a fun day! See you tomorrow!