"We come from a land down under" -Men At Work

Sea spiders (Ammothea glacialis) which are in a class all their own called Pycnogonida hang out on a rock in the lab. Photo courtesy of A. Toh.

Sea spiders (Ammothea glacialis) which are in a class all their own called Pycnogonida hang out on a rock in the lab. Photo courtesy of A. Toh.

I watch the slow movement of the thin orange colored legs. They reach out so gently as if frightened to make a move. In fact, they aren't frightened at all. These sea spiders are just slow movers. The -1.8°C waters that they call home results in a slow metabolic rate which results in slow movement.

The research team, led by Dr. Amy Moran, and including graduate students Aaron Toh and Graham Lobert, that I am partnered with in Antarctica is studying marine ectotherms. Ecto means external or on the outside. Marine ectotherms are animals that cannot regulate their body temperature so their body temperature changes based on the temperature in the external environment. We often call ectotherms cold-blooded.

Compare these ectotherms to people and other animals that are endotherms. Endo means within so endotherms are capable of making their own heat within their body. Humans are generally 98.6°F inside of our bodies. We aren't going to change that temperature based on our environment. Instead, we have to maintain 98.6°F. This is why we sweat to cool us off when we get too hot and shiver to warm us up when it's too cold. It's also why we must eat. We turn our food into energy through metabolism and that energy generates heat that keeps us warm. We often call endotherms warm-blooded.

Amy Osborne bundled up to stay warm on the sea ice. As an endotherm, this a behavioral strategy for me to stay warm. I should also be sure to eat so I can generate internal heat. Photo courtesy of Denise Hardoy.

Amy Osborne bundled up to stay warm on the sea ice. As an endotherm, this a behavioral strategy for me to stay warm. I should also be sure to eat so I can generate internal heat. Photo courtesy of Denise Hardoy.

This sea urchin, while it might like to decorate itself, is an ectotherm so it doesn't need a coat, its body temperature will change with the changing temperatures.

This sea urchin, while it might like to decorate itself, is an ectotherm so it doesn't need a coat, its body temperature will change with the changing temperatures.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) which I mentioned in a previous journal entry, keeps the Antarctic marine ecosystem fairly isolated from the rest of the ocean. This results in an environment with very little genetic exchange with the rest of the global ocean. The marine ectotherms found in the chilly waters around Antarctica are adapted to live in this unique and isolated habitat.

Here are a couple of specific characteristics of the marine ectotherms that call this watery winter wonderland home:

low metabolic rate which results in slow movements and less need for oxygen

slow development and growth meaning it takes a longer time for eggs to hatch and larvae to develop into the next stage

The research team is specifically focusing on the growth and development of sea spiders and nudibranchs, also known as sea slugs. In a future post I will talk more about the fascinating research they are doing. For now, let's meet the animal superstars of this project.

Today's marine ectotherm superstar is the sea spider!

Sea Spiders

One of the many incredible things about sea spiders that live in the Antarctic is their notable size. There are 1300 species of sea spiders on earth. Antarctic sea spiders make up 22% of sea spider species and with some Antarctic species at over one foot in length they are the largest. Compare them to a sea spider along the California coast that is less than an inch and we realize the giants that are creeping along the Antarctic sea floor. Like many marine invertebrates in Antarctica, sea spiders experience polar gigantism, which means in the polar regions they are larger than sea spiders in other parts of the world!

A giant sea spider in the Antarctic Photo by Timothy R. Dwyer (PolarTREC 2016), Courtesy of ARCUS

A giant sea spider in the Antarctic Photo by Timothy R. Dwyer (PolarTREC 2016), Courtesy of ARCUS

Sea spiders are in the phylum Arthropoda meaning jointed foot. Arthropods make up 75% of life on earth! They have an exoskeleton, which is called a cuticle and is made of chiton. This is quite different from humans who have a backbone, are called vertebrates, and have a backbone that is made mostly of collagen. Some other arthropods you might know are beetles, butterflies, crabs, and spiders.

Amazingly, sea spiders don't have gills or lungs, instead they actually have holes in their cuticle through which they get their oxygen! Imagine walking around and not worrying about taking a breath. Instead the oxygen diffuses into their bodies!

Check out the jointed appendages on this sea spider known as Ammothea glacialis.

Like all Arthropods, this sea spider (Ammothea glacialis) has jointed legs. Photo courtesy of A. Toh.

Like all Arthropods, this sea spider (Ammothea glacialis) has jointed legs. Photo courtesy of A. Toh.

Sea spiders also belong to the subphylum Chelicerata which means clawed horn. They don't have antennae but they do have a body part called chelicertae which are appendages that they use to feed.

When we get down to the class level that's when sea spiders and spider spiders, you know the ones walking around your house, diverge. The spider you've probably seen walking around is an Arachnid and sea spiders are in their own class called Pycnogonida.

A female and male sea spider (Ammothea glacialis) on a rock in the lab. The male is carrying the orange sea spider eggs. Photo courtesy of A. Toh.

A female and male sea spider (Ammothea glacialis) on a rock in the lab. The male is carrying the orange sea spider eggs. Photo courtesy of A. Toh.

Similar to seahorses, in which the males carry the eggs around in a pouch, male sea spiders are also the caregivers for the eggs. The males carry the eggs around with their ovigers. Ovigers are a part of the sea spider that looks like legs and are used for carrying eggs and cleaning themselves.

A male sea spider (Ammothea glacialis) carrying eggs with its ovigers. Photo courtesy of A. Toh.

A male sea spider (Ammothea glacialis) carrying eggs with its ovigers. Photo courtesy of A. Toh.

I find the most fascinating thing about sea spiders is that they have their guts in each of their legs. Scientists actually observed the movement of the sea spiders digestive system by looking at their legs! Once a sea spider has used its proboscis, which is the long part protruding from its head, to pierce their prey and suck up its juices, the food then travels to the sea spiders legs to be digested. Amazingly, researchers observed, these leggy guts are what pumps blood through the sea spider.

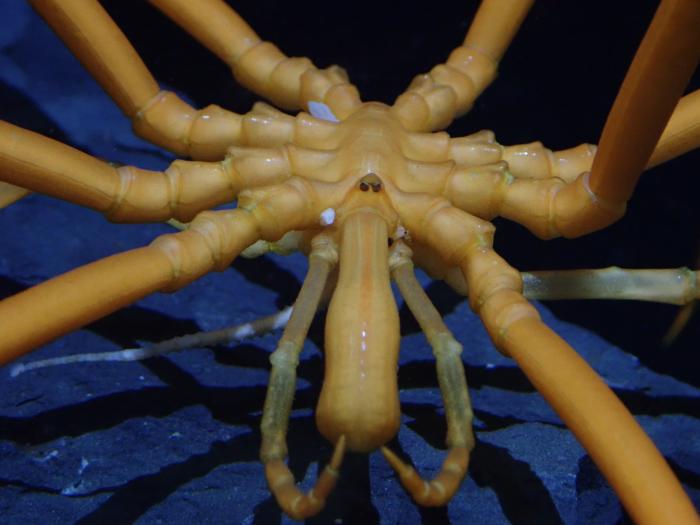

This close up of a sea spider (Colossendeis sp.) shows its eyes, long proboscis in the center, and the chelicerae on either side of the proboscis. Photo courtesy of A. Toh.

This close up of a sea spider (Colossendeis sp.) shows its eyes, long proboscis in the center, and the chelicerae on either side of the proboscis. Photo courtesy of A. Toh.

Not only are a sea spiders legs a great spot for them to get their oxygen and digest their food, it's also the spot where the females hold her unfertilized eggs. Once she is ready to have them fertilized she releases them from her leg.

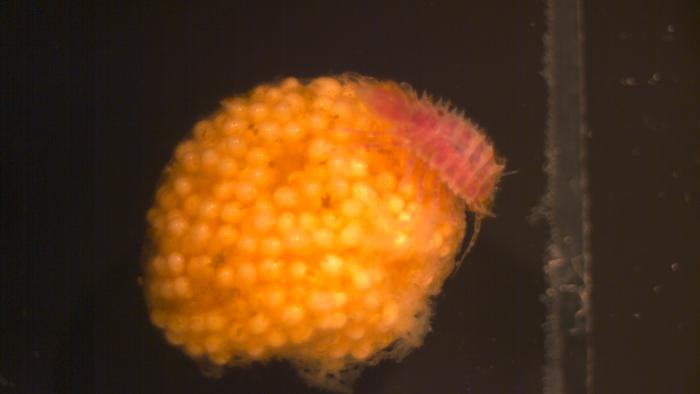

Sea spider (Ammothea glacialis) egg mass with an isopod on it. Photo courtesy of A. Toh

Sea spider (Ammothea glacialis) egg mass with an isopod on it. Photo courtesy of A. Toh

Well, I hope you enjoyed a little glimpse into the world of sea spiders. We'll learn more about them as we go. Tomorrow we'll find out more about nudibranchs! As always, feel free to ask questions or make comments below. I'm spending time with sea spider experts so I can ask the experts any questions you have.

Antarctic sea spiders stacked on top of one another. Photo courtesy of A. Toh.

Antarctic sea spiders stacked on top of one another. Photo courtesy of A. Toh.

Don't forget the trivia questions from October 23rd's post need to be answered by midnight California time on October 31st!

And, if you were fascinated by my journal about diving under the ice check out this video I about made about our diving expedition.

Comments

Add new comment