This journal is brought to you by...

Dr. Michelle Shero holding your flags. Photo credit: Alex Eilers

Dr. Michelle Shero holding your flags. Photo credit: Alex Eilers

- Mrs. Audrey Stagg and her 1st grade class at Medina Elementary School

- Robin Porter and her kindergarten class at Riverwood Elementary School

- Jade Douglas and her 3rd grade class at Lakewood Elementary School

This post was written by Dr. Michelle Shero.

A lot of what we want to know about our Weddell seals revolves around ENERGY (i.e. calories) – how much the seals need, how they use it and where they get it from. For seals, most of the answers lie in the animal’s diving and foraging behavior. But how can we measure this? Marine mammals can be exceptionally hard to study, because they catch their prey and forage underwater where we can’t see them. So, the marine mammal field started relying on “tags” to collect the information for us.

The first tag

The very first tag was tried-out on none-other-than the Weddell seal in McMurdo in the 1970’s by Dr. Gerald Kooyman. It was a modified kitchen timer that recorded the animal’s depth in the water every few seconds, and it drew the dives onto camera film. This was the first Time-Depth Recorder (TDR).

Weddell seal with the first time depth recorder used in 1978-79. Photo credit: Dan Costa

Weddell seal with the first time depth recorder used in 1978-79. Photo credit: Dan Costa

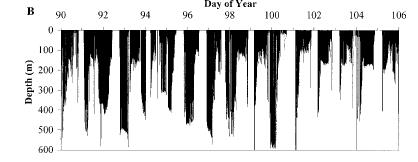

Dive record from the Weddell seal with the first time-depth recorder. Photo credit: Dan Costa

Dive record from the Weddell seal with the first time-depth recorder. Photo credit: Dan Costa

The first time-depth recorder built by Kooyman and Billups. Photo credit: Michael Castellini

The first time-depth recorder built by Kooyman and Billups. Photo credit: Michael Castellini

Changing technology

Since then, tags have gotten smaller and they can do much more! The first time Alex came to McMurdo in 2012, we were using satellite-relay tags that we glued to the animal’s fur. We used these tags to determine where our Weddell seals were going across the 8-month, dark and cold winter. This tag measures dive duration, whether animals are hauled-out or diving, depth with a pressure sensor and numerous water measurements. Water circulates in ‘masses,’ each with its own unique characteristics: different temperatures, salt content (salinity) and nutrients.

Large format, satellite-relay loggers used to collect dive behavioral data, seal position and oceanographic data during the Antarctic winter from 2010-2012. Photo credit: Roxanne Beltran, MMPA Permit # 17411

Large format, satellite-relay loggers used to collect dive behavioral data, seal position and oceanographic data during the Antarctic winter from 2010-2012. Photo credit: Roxanne Beltran, MMPA Permit # 17411

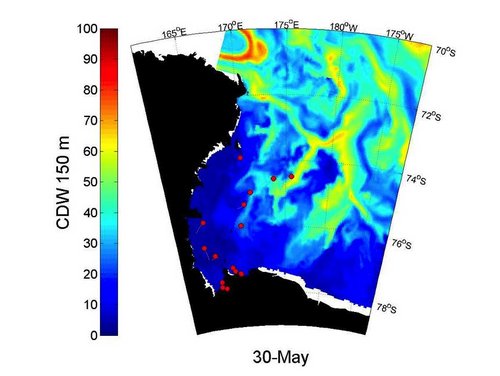

In Alex’s second season in 2014, we wanted to see whether seals preferred to forage at specific areas with particular water masses. Between knowing the animal’s location and the water measurements, we were able to determine that they travel up to 800 km (~500 miles) over the winter to reach Circumpolar Deep Water that has lots of nutrients and prey. When the seals came to the water’s surface, these tags would transmit the information it had collected. This information would be recorded by a satellite orbiting 850 km (~530 miles) above the earth’s surface, which then retransmitted the information back to us. So, once we attached the tags to the seals, a lot of the data appeared on our personal computers back home in the United States. With a satellite-relay tag, we will never receive all the information this tag collects. Many of the transmissions from the tags aren’t received by the satellites because they aren’t overhead at the time the message is sent. This creates ‘holes’ in this dataset.

Weddell seals’ locations during the austral winter relative to circumpolar deep water. Photo credit: Kim Goetz

Weddell seals’ locations during the austral winter relative to circumpolar deep water. Photo credit: Kim Goetz

If these satellite tags can do so much, then why are we using different tags for this project? Well, because we had to glue these tags to the seal’s fur, the tags are shed each year during the annual molt. This whole project is focusing on what the seals are doing across the molt… so we really need them to keep those tags! Therefore, we didn’t want to glue tags and rely on the seals keeping their fur. Instead, we decided to give the seals flipper-tags that collected similar information. But for seals to carry tags on their flippers, the instruments needed to be a lot smaller!

Our study period relative to the Weddell seal’s annual calendar. Photo credit: Roxanne Beltran

Our study period relative to the Weddell seal’s annual calendar. Photo credit: Roxanne Beltran

The trade-off is that smaller tags have smaller batteries, and so they can do less. To get all the information we need, we have 2 tags. The first is a time-depth recorder (notice how much smaller the tags from 2013 are than the very first tags from 1978!!). This time-depth recorder collects a depth reading every 6 seconds the entire time it’s on a seal. But, it doesn’t transmit the data to a satellite. We must find this seal again and recover the tag in order to get ANY of the information from it--- it’s a little more of a gamble. If we can get the seal back, we get all the data from this tag and there are no holes in the dataset, BUT if this seal leaves McMurdo we would never get any of its dive data at all.

Time-depth recorder attached to Weddell seal flippers during this project. Photo credit: Michelle Shero, MMPA Permit # 17411

Time-depth recorder attached to Weddell seal flippers during this project. Photo credit: Michelle Shero, MMPA Permit # 17411

To help us relocate the seals and get our instruments back, the 2nd flipper gets another tag. A few of our seals will get a very small satellite-relay tag. Instead of the 600 g tag glued to the animal’s fur from last project, this tag weighs less than 50 g on the seal’s flipper. This tag transmits to a satellite letting us know where the seal is, but will not collect additional information about the seal’s dives (duration, depth) or oceanographic measurements like the larger tag (water temperature, salinity). These satellite tags have shown us that to prepare for the molt when Weddell seals haul-out and don’t forage much (for about 1 month), some seals go to nearby areas where there may be fewer seals to compete with for food.

Smaller satellite-relay logger on a Weddell seal flipper. Notice all the fur that is shed during the annual molt. Photo credit: Michelle Shero, MMPA Permit # 17411

Smaller satellite-relay logger on a Weddell seal flipper. Notice all the fur that is shed during the annual molt. Photo credit: Michelle Shero, MMPA Permit # 17411

Where 6 satellite-tagged Weddell seals went during the summer. Seals stayed local. Photo credit: Michelle Shero

Where 6 satellite-tagged Weddell seals went during the summer. Seals stayed local. Photo credit: Michelle Shero

Most of the seals get a very-high frequency (VHF) tag. All this tag does is emit electromagnetic waves that can be picked up by a radio receiver. If we are scouting in the area with a radio and receiver, we will hear a “ping” that tells us the seal is nearby. A VHF tag does not collect any further information for us.

Very high frequency (VHF) tags help us to relocate animals. Photo credit: Michelle Shero and Gregg Adams, MMPA Permit # 17411

Very high frequency (VHF) tags help us to relocate animals. Photo credit: Michelle Shero and Gregg Adams, MMPA Permit # 17411

Thus, each instrument we can use to study marine mammals has its own pros and cons, with regards to size, how it’s attached to study animals, the information it can collect, the battery life and how to get the data back. All of these factors have to be carefully considered when choosing the best way to successfully complete our research goals.

Comments