This journal is brought to you by…

Stefan (our fuel man) holding three of your flags. Photo credit: Alex Eilers

Stefan (our fuel man) holding three of your flags. Photo credit: Alex Eilers

- Sue Tony’s 6th graders at St. Philomena Catholic School

- Becky Shimp’s 7th graders at St. Edward Catholic School

- Mrs. Shadensack’s 8th graders at Immaculate Conception Catholic School

Happy Birthday Seals!

Do any of you have a birthday in October or November? I do! I get so excited to celebrate and eat cake every year, but now that I’ve been studying Weddell seals, I have another reason to get excited during the fall. I get to share my birthday with all the seals!

While our October and November is when the weather is just starting to get cooler, down on the ice, it’s spring, and heading into the warmest time of year (but it is still pretty cold). That also makes it the healthiest time of year for a seal to have a pup because pups are most likely to survive their first few months if they stay warm under the sun on the ice. Could you imagine being born into a world of total darkness and extreme cold? Thankfully, seals and humans are both safe from that, and, for seals, it’s because of a special adaptation in the female seals’ bodies. Follow along as my team member, Michelle, tells us more about it!

This post is a guest journal written by post-doctoral researcher Michelle Shero.

Start. Stop. Wait. Let’s Go!

You’ll see that a common theme across these journals is that we are trying to see how a female Weddell seal’s health influences her ability to reproduce – or have pups. Weddell seals ‘skip pup’ more often than a lot of other seal species. On average, a female Weddell seal will only have a pup every 2 out of 3 years. We wanted to figure out why these females don’t have a pup every year and what makes a very successful mom that produces lots of pups.

Our hypothesis is that if a female is too skinny, or hasn’t been foraging very well, her body may tell her that it’s better to ‘skip’ pupping – or just not become pregnant that year. Or, if a female becomes pregnant and doesn’t forage very well afterwards, she may lose the pregnancy a few weeks or a few months later.

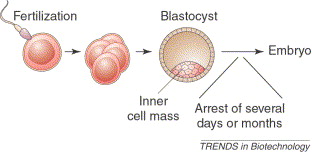

Typically, seals have what we call an ‘embryonic diapause’. What this means is that during the breeding season, a female’s egg will be fertilized and grow a little bit (creating a blastocyst), but the female doesn’t start what we typically think of as ‘pregnancy’ right away. This blastocyst’s growth is put ‘on pause’ for weeks to months, until cues from the environment or from the female tell it to implant in the uterus and start growing again. Once growth resumes, the pregnancy starts to cost the female more energy. So the timing of diapause and pregnancy are very important!

Embryonic diapause. Photo credit: Rose-John 2002

Embryonic diapause. Photo credit: Rose-John 2002

In the field

So how do we know that a seal is pregnant?

We can see that a seal is pregnant using an ultrasound machine.

Ultrasound machine

Basically, an ultrasound uses sound waves to ‘see’ inside a body (in our case, a seal). It sends sound waves, too high for us to hear, into a body. The sound hits a surface (like tissue, bone, muscle etc.) and bounce back, like an echo in a cave, to produce a picture.

Doctors often use ultrasounds on pregnant women to monitor the growth of a baby; we use it to detect if a seal is pregnant. Not very many people know how to do this in wild animals like our seals – so the team has had special veterinarians come to Antarctica, and they are the experts!

This is the ultrasound machine we use. Photo credit: Gregg Adams

This is the ultrasound machine we use. Photo credit: Gregg Adams

Advanced technology allowing us to use an ultrasound in the field – and even the Antarctic! – is quite a feat and allows us to see a lot about the seal’s pregnancy without disrupting the pregnancy at all.

The Embryos

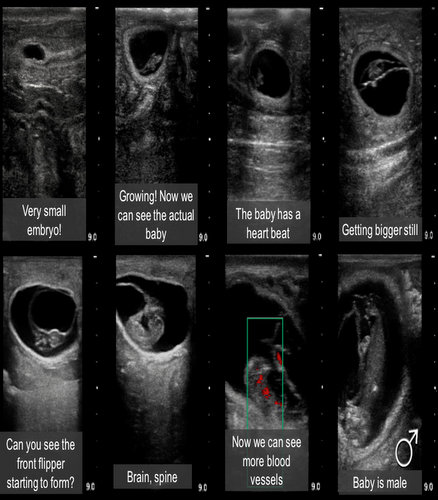

Now, in the January-February field season, the team comes back to see if the seals we tagged in October-November are pregnant. So, since 1-2 months have gone by and diapause would have ended before then, we should be able to see growing babies (or embryos). Not all of our seals would necessarily be pregnant, so the ultrasound would allow us to tell which females were pregnant, and which were not.

We can estimate how pregnant the seal is by the size of the embryo. Larger embryos will be older. We can see these embryos just a few days after pregnancy starts. The smallest embryo we’ve seen was just 3 millimeters in size! Using the ultrasound machine, we can measure exactly how big the baby is.

Having the ultrasound machine means that, in addition to just looking at how healthy the mom is, we can look at how healthy the baby is, too. As embryos get larger, we can see the heartbeat, the head and brain, and the flippers. In some big embryos, we can sometimes tell if the baby will be male or female!

A few of the ultrasound pictures we get back, showing very small to large babies. Photo credit: Shero, et al., 2015 (pictures modified)

A few of the ultrasound pictures we get back, showing very small to large babies. Photo credit: Shero, et al., 2015 (pictures modified)

Outcomes and Questions

Once we know that a seal is pregnant, we can start to look at patterns and ask questions…

- Was it our large females with lots of energy stored as fat that became pregnant?

- Was it the females with low stress levels?

- Which factors are important for whether or not the seal will become pregnant?

We can then find these exact same seals the next year to see if they were able to keep ‘growing’ the pregnancy, through the harsh Antarctic winter – to give birth to a pup the next year!

Weddell seal pup. Photo credit: Michelle Shero, MMPA Permit # 17411

Weddell seal pup. Photo credit: Michelle Shero, MMPA Permit # 17411

Comments