This journal is brought to you by…

Dr. Gregg holding three of your flags. Photo credit: Alex Eilers

Dr. Gregg holding three of your flags. Photo credit: Alex Eilers

- Ms. Karen Davis’s 5th grade class at Eastwood Elementary

- Ms. Puterbaugh’s 5th grade class at Chillicothe Elementary School

- Ms. Amanda Nixon’s 5th grade class at Riverwood Elementary

Weddell Seal Dives

Every scientific research project begins with questions. This project is looking at the timing of female Weddell seals’ ‘big events’ – pupping and molting and how the health or condition of the animal affects if and/or when a seal gives birth the next year. There are many factors that come into play when trying to answer that question. An important factor is the animal’s ability to forage (hunt) for food. The Weddell seal does its foraging by diving.

But, before we can figure out how seals use their energy, we need to look at how they get their energy – from eating! And seals get their food by diving! In this lesson we will dive into how a seal gets its food! We’ll look at the data gathered by the research team and see what conclusions we can make.

The data we’re using in this lesson comes from a time-depth recorder (TDR) which is attached to the middle of the hind flipper of each study seal.

Here is a Weddell seal with a TDR tag attached. We use the data from the TDR to learn about Weddell seal dives. Photo credit: Roxanne Beltran, MMPA Permit # 17411

Here is a Weddell seal with a TDR tag attached. We use the data from the TDR to learn about Weddell seal dives. Photo credit: Roxanne Beltran, MMPA Permit # 17411

The team attached TDR’s to 24 female seals in November – December of 2014 and recovered them an average of 60 days later, in January – February of 2015. The recorders are programmed to collect the seal’s depth every 6 seconds. Let’s take a look at what the records show us! This is the full dive record of a typical female seal over a two-month period of time. The red circle marks the part of the dive that we’ll examine more closely.

This is a full dive record of a typical female seal over two months. Photo credit: Roxanne Beltran, MMPA Permit # 17411

This is a full dive record of a typical female seal over two months. Photo credit: Roxanne Beltran, MMPA Permit # 17411

For our purposes, we will define a ‘single dive’ as one that is:

* Over 10 meters deep

* Lasts at least 30 seconds and is

* Followed by a period at the surface

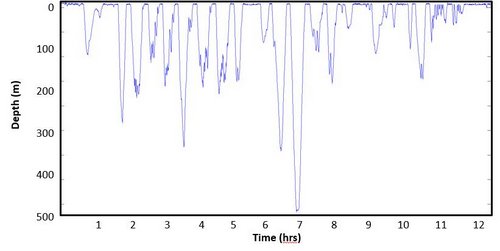

How many dives can you find in the picture below?

How many dives can you find in this picture? Photo credit: Roxanne Beltran, MMPA Permit # 17411

How many dives can you find in this picture? Photo credit: Roxanne Beltran, MMPA Permit # 17411

We were able to find 22 dives. Did you come up with similar answers? Some of these dives are tricky to count. Researchers look for the number of dives as well as trends. Some of their questions might be, is there a tendency for a seal to dive a certain depth or are there patterns in their diving behavior?

Let’s go for a dive!

These Weddell seals are underwater getting ready to go for a dive. Photo credit: Knowledge Era

These Weddell seals are underwater getting ready to go for a dive. Photo credit: Knowledge Era

Now that you know what a Weddell seal dive looks like, let’s see how the lungs, muscles and blood all work together!

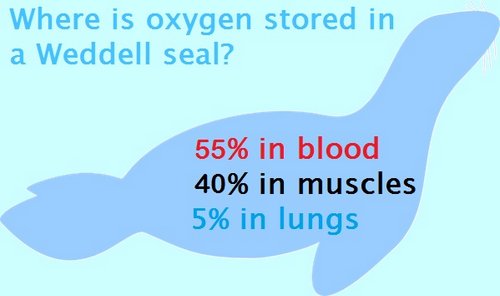

There is a lot going on when a Weddell seal takes a dive! Since they have no access to air, their bodies have to store oxygen to be used underwater. Marine mammals have much larger blood volumes (about 3x that of a similarly-sized terrestrial mammal). Within this greater blood volume, they also have greater hematocrit (packed red blood cell volume; about 1.5x terrestrial mammal), and they also have higher blood hemoglobin concentrations (about 2x terrestrial mammal) to carry more oxygen. In the muscles, divers have 10-20x the amount of myoglobin as a terrestrial mammal of similar size. It’s a bit like a scuba tank! In order for these large oxygen stores to actually be of use to divers, the other fundamental concept is that they must be able to conserve these stores and use them slowly. Three main body parts all work together to help Weddell seals on their deep dives: their lungs, blood and muscles.

Since we’ve learned about these three areas already in detail, we can start to see how they work together during a typical Weddell dive.

How it works

Before a dive, a Weddell seal will exhale most of the air out of its lungs. Air is very buoyant, which means it wants to float. By exhaling, the seal makes itself less buoyant so that it will easily sink when it dives. After exhaling, and as it descends, the seal’s lungs collapse due to water pressure.

The Dive Reflex

All mammals, including humans, have what is known as the dive reflex. It happens when mammals dive into cold waters (less than 70°F), specifically when the cold water hits their face. As your body temperature drops, your body will begin to shut down processes that are not essential in order to keep important processes working – like your brain and your heart. The colder the water, the faster the dive reflex kicks in.

In humans, this dive reflex is an involuntary reflex used in emergency situations. Involuntary means you can’t control it. Have you ever been to the doctor and had your knee hit with a little hammer? Your leg kicked forward, right? That’s an involuntary reflex. Humanshave been known to live after a “near drowning” because of their dive reflex.

What’s cool about Weddell seals is that they use their dive reflex all the time! At the start of a dive, seals can drop their heart rates to less than 10 beats per minute (Do you know what your heart rate is when you exercise?). At the same time, their bodies start to constrict their blood vessels, making them really small and slowing down how much blood and oxygen are delivered to many organs and the muscles. This process keeps oxygen for the organs that are most important – the heart, brain and lungs. These organs must have oxygen at all times.

Most of the oxygen that the seals use for their dives is in their blood. The blood of a Weddell seal has a lot more hemoglobin protein in it than a human’s does. Hemoglobin is the oxygen carrier. It binds to oxygen and carries it throughout the body. Because seals have a lot of hemoglobin, they can store more oxygen to be used during their dive. Not only do they have more hemoglobin, they also have a lot of blood. More blood equals more oxygen! During the start of a series of dives (a bout), the spleen will also squeeze out a whole bunch of new red blood cells that already have oxygen bound to them for an extra boost.

“Lungs full of oxygen, an elephant seal (top) begins a dive. By one hundred feet down (right center), the animal's lungs have collapsed and oxygen has been transferred to the spleen and muscles for storage.” Photo credit: Science Notes UCSC

“Lungs full of oxygen, an elephant seal (top) begins a dive. By one hundred feet down (right center), the animal's lungs have collapsed and oxygen has been transferred to the spleen and muscles for storage.” Photo credit: Science Notes UCSC

In the muscles, there is also a protein called myoglobin, which stores oxygen. Weddell seals have much more myoglobin in their muscles than humans. The darker the muscle, the more myoglobin there is, and Weddell seal muscles are almost black! The seals really need this oxygen in the muscles for exercise and foraging on dives.

Altogether, the lungs will store about 5% of the seal’s oxygen during a dive. The blood stores about 55% and the muscles about 40% of the oxygen in the seal’s body.

Where is oxygen stored in a Weddell seal? Photo credit: Alex Eilers

Where is oxygen stored in a Weddell seal? Photo credit: Alex Eilers

Coming up for air

The oxygen that the seals have stored won’t last forever. Seals have to come up for air. The average dive is about 20 minutes long. But they can stay underwater for over an hour! Longer dives are generally used for escaping predators, finding a breathing hole or exploring new territory. A shorter dive that lasts less than 20 minutes is usually for finding food. This type of dive is more beneficial for the seals. Why do you think that is?

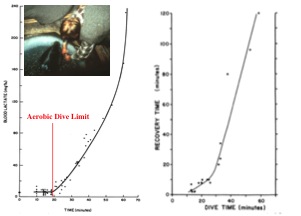

When you work your muscles at a faster rate than oxygen can get to them, you begin to produce lactic acid. On a long dive, these seals begin to produce lactic acid as their muscles begin to run out of oxygen. However, this lactic acid remains in the muscles until they resurface. Once they resurface, this lactic acid gets “washed out” to the rest of their body. Before they can make another long dive, they have to get rid of the lactic acid in their bodies. Once lactic acid is produced, the time needed to clear it out increases exponentially! So, it is definitely better for a seal to come up for air before there is a large buildup of lactic acid. That’s why most dives we’re seeing are around 20 minutes long – that’s how long the oxygen stored in their bodies will last.

After the aerobic dive limit, lactate levels increase. After lactate levels increase, seals spend much greater recovery times at the water’s surface after a dive. Photo credit: Kooyman et al. 1980

After the aerobic dive limit, lactate levels increase. After lactate levels increase, seals spend much greater recovery times at the water’s surface after a dive. Photo credit: Kooyman et al. 1980

Getting some tips from Weddell seals!

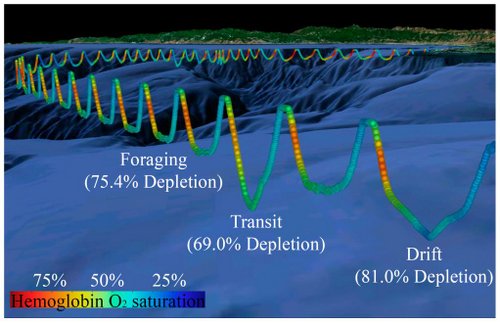

When humans exercise, they need to keep some spare oxygen in the body. They can never use up all of it. Not only do Weddell seals have more oxygen than humans and use it more slowly, but they can almost use it all.

‘Blue’ shows oxygen being depleted, or used-up, by the end of a dive. Less is bound to **Hemoglobin** so it becomes less **saturated**. Photo credit: Meir et al. 2013

‘Blue’ shows oxygen being depleted, or used-up, by the end of a dive. Less is bound to **Hemoglobin** so it becomes less **saturated**. Photo credit: Meir et al. 2013

We aren’t the only people interested in Weddell seals! They are the champions of the dive reflex! Doctors look at these seals to see how they recover from a dive. Free-divers also look to the Weddell seal for some tips! Free-diving is a competitive sport and hobby where people dive to great depths with no scuba gear! One of its champions, Sebastian Murat, actually exhales before diving! Sound familiar?

Our diving reflex is one of the many amazing things about our bodies, but don’t try to use your diving reflex! It’s your body’s way of protecting itself in an emergency situation! What’s cool about Weddell seals is the way their dive reflex enables them to thrive in a unique environment like Antarctica!