This journal brought to you by...

- Donna Hawkins and her 1st graders at Jackson Elementary

- Melody Tannehill and her Kindergartners at Hutchison

- St. Ann 5th grade Sparks students

Thank you - Jackson Elementary, Hutchison and St. Ann Schools!

Thank you - Jackson Elementary, Hutchison and St. Ann Schools!

A Closer Look at … Weddell Seal Blubber

What’s all the blabber about blubber?

I’m sure you’ve noticed by now how HUGE Weddell seals are, and one of the reasons for their enormous size is that 30-40% of their bodies are fat! Actually, it’s a special kind of fat, or lipid, called blubber. Blubber has a very important purpose for Weddell seal. Can you guess what it is?

Insulation

Yes - to keep them warm! They live in such a cold environment that they actually need extra fat to insulate their bodies. Blubber traps heat inside their bodies, keeping their core temperature very warm - even if they are hauled out on ice. In fact, Weddells are very rarely cold because their core temperature stays around 100°F. That's close to our bodies’ normal temperature 98.6°F. Think about it this way: when we get cold, the first thing we do is grab a jacket or blanket to warm up. So we use an external insulator. Weddells don’t mind if their skin is cold because they have an internal insulator that keeps their organs warm. When seals are hauled out on a sunny day, they are more likely to be hot than cold, and their warm bodies will actually melt the ice or snow they are laying on.

Here I am showing off my insulation. I have two other layers under my Big Red and I'm still cold.

Here I am showing off my insulation. I have two other layers under my Big Red and I'm still cold.

Can you see the seal outline? This impression was made because their warm body melted the surrounding snow and ice.

Can you see the seal outline? This impression was made because their warm body melted the surrounding snow and ice.

So how much blubber do Weddells have, anyway?

To answer that question we have to know what seal are doing throughout the year. They spend different proportions of time diving underwater or hauled out on ice. Between October and January (which is spring and summer in Antarctica), Weddell seals are giving birth, reproducing, and molting. During this period, they spend less time diving and foraging for food, so their blubber layer thins out. By the end of summer Weddells are at their thinnest and they are ready to start actively foraging to build up their fat and energy supply. So, during the rest of the year, from February to September, Weddells spend a much larger proportion of time underwater doing just that.

This is an annual cycle for the Weddell seal and shows when the seals is actively foraging or actively hauled-out in the ice. Image Credit: Michelle Shero, 'Weddell Seal Body Composition'.

This is an annual cycle for the Weddell seal and shows when the seals is actively foraging or actively hauled-out in the ice. Image Credit: Michelle Shero, 'Weddell Seal Body Composition'.

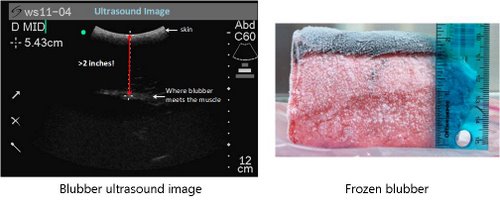

During the Antarctic fall and winter, Weddells can have more than 2 inches of blubber underneath their skin. Considering their massive weight of 400-600 kilograms, or 800-1320 pounds, that could be up to 240 kilograms, or 528 pounds of pure blubber! WOW!

How thick is blubber? Scientists measure the thickness of seal blubber with ultrasound technology. Image credit: Michelle Shero, 'Weddell Seal Body Composition'.

How thick is blubber? Scientists measure the thickness of seal blubber with ultrasound technology. Image credit: Michelle Shero, 'Weddell Seal Body Composition'.

Blubber = Energy for Weddells

Clearly, blubber is important for insulation; but it’s also really important for another reason. Seal bodies can break down their blubber layer to create energy when they really need it - like when they’re hauled out on ice instead of hunting for food. Remember: when seals are hauled out, they’re not just wasting time. True, their bodies need that time to rest but they also spend that time molting and pupping – two things that take a lot of energy. Female seals also need extra energy during the pupping season because it takes quite a bit to produce milk and feed their pups. Their milk is made up of 60% fat! So pups are not born with much blubber - but they get this high-fat milk from their mothers to quickly make their own blubber layer. So in a way, it’s like moms give their pups about 50 kilos, or 110 pounds of their blubber in their first few weeks of life – that’s about 5 pounds per day!

This pup is working on his blubber layer. Photo credit: Daniel Costa.

This pup is working on his blubber layer. Photo credit: Daniel Costa.

Bigger might just be better

The amount of blubber a seal has gives scientists an estimate on how successful the seal has been when foraging for food. And in this case - bigger just might be better. Think of it this way - if a seal is thin, it most likely has a thin blubber layer, which means it doesn’t have a lot of energy reserves or as much insulation. But the seal need to swim to catch fish (which takes a lot of energy) in order to build up those energy reserves. And, if you are a seal without a thick blubber layer and you’re in the water, you may lose heat more rapidly, which means it costs you more (energy that it) to be in the water. So there’s kind of a trade-off there – it’s going to be more expensive for a skinny seal (in terms of energy) to be in the water, but the seal needs to be in the water in order to catch food and get fat again. So a thick blubber layer just might be better!

What can we learn from blubber?

Fats in mammals – primarily in the blubber layers - come directly from the fats in their diet. So our team is using blubber samples to find out what the seals have been eating. But how do they do that?

Blubber sample!

Blubber sample!

- First, we take a little sample of blubber in the field.

- That blubber gets analyzed for the various lipids - remember this comes from what they eat.

- Then, we find out what lipids are in the seals prey - like Silverfish, Antarctic Cod etc.

- Finally, the team will do a little mathematical analysis and a bit of matching to figure out what the seal has been eating.

Ok, to be honest, the team laughed when they read the 'little bit of math' thing. Evidently, there is much more to it than that - but they do the math part back at the lab.

Digging deeper

Michelle Shero, a graduate student at UAA (University of Alaska at Anchorage) plans on doing work with the Weddell seal correlating the seal blubber percentage to their seals dive shapes.

Fat seals float!

Seals can passively drift during their dives, and skinny animals will 'sink' in the water column. But animals that are about to give birth, or those that have been very successful in finding food, have a lot more fat. Fat is less dense than water and this makes these seals more buoyant- so they float! Scientists have even linked the speed and angles of these dives with the proportion of the body made up of blubber.

Dive profile. Image credit: Schreer et al., 2001.

Dive profile. Image credit: Schreer et al., 2001.

Typical pinniped dive profiles.

- Square indicates equal time devoted to ascent and decent, with excess time spent searching the benthos (bottom).

- V shows equal time spent on ascent and descent, but virtually no bottom time.

- Skewed right indicates more dive time allocated to ascent relative to descent.

- Skewed left shows more dive time devoted to descent rather than ascent

Amazing stuff - isn't it!

The activity/animal depicted was conducted pursuant to NMFS Permit No 87-1851.