Rangifer tarandus platyrhynchus

Today I visited Dr. Wylie’s 9th grade biology classes at Mill Creek High School in Hoschton, Georgia. Thank you Dr. Wylie and Mill Creek students. You were great!

Mrs. McNeal talking with Mill Creek students about the Svalbard reindeer

Mrs. McNeal talking with Mill Creek students about the Svalbard reindeer

The topic of the day (and our biology connection) was the Svalbard reindeer. Here are some quick facts:

- North American caribou and Eurasian reindeer are the same species, Rangifer tarandus.

- The Svalbard population, Rangifer tarandus platyrhynchus, is an isolated subspecies found only on Svalbard.

- The Svalbard reindeer is the smallest species of reindeer and exhibits insular dwarfism or reduction in size over many generations when a population’s range is limited, such as on an island.

Compare the two pictures below:

Svalbard reindeer, the smallest subspecies of reindeer

Svalbard reindeer, the smallest subspecies of reindeer

Strolling reindeer in the Kebnekaise valley, Sweden

Strolling reindeer in the Kebnekaise valley, Sweden

Svalbard reindeer have some interesting adaptations as a result of unique environmental pressures, such as:

- Shorter legs (no natural predators)

- Smaller size (conserves limited resources)

- Stockier build (stores lots of fat during winter)

- Larger stomach (needed to digest poor quality food)

- Different behaviors and social structure (doesn’t migrate, does not form herds, males do not compete)

The students at Mill Creek had many intriguing questions and insights into this unique animal and its fascinating evolutionary path. I can’t wait to see Svalbard reindeer in person. I will post pictures when I do.

Curious Students Always Have the Best Questions

Thank you, Mill Creek High School for asking great questions for upcoming “Take A Closer Look” journals. You have me thinking and I will be looking for answers to your engaging questions while in Svalbard. Stay tuned to see your questions answered in upcoming journals.

Mill Creek students created engaging "Take a Closer Look" questions

Mill Creek students created engaging "Take a Closer Look" questions

Dr. Wylie

Thank you, Dr. Wylie for inviting me to you classroom. Mill Creek students are super kids!

Dr. Wylie and Mrs. McNeal at Mill Creek High School's 9th grade biology classes

Dr. Wylie and Mrs. McNeal at Mill Creek High School's 9th grade biology classes

Take A Closer Look

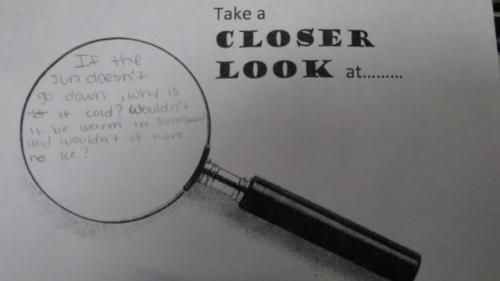

Our “Take a Closer Look” question today comes from Gabrielle R. from Mill Creek High School. It is “If the sun doesn’t go down, wouldn’t it be warm in Svalbard and wouldn’t it have no ice?”

Today's "Take a Closer Look" question comes from Gabrielle R. Mill Creek

Today's "Take a Closer Look" question comes from Gabrielle R. Mill Creek

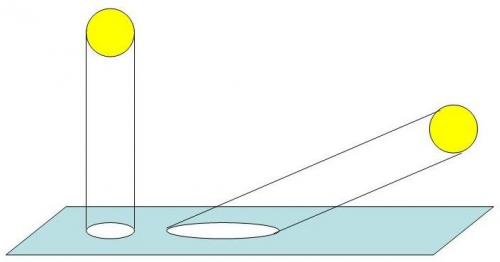

Great question! To be clear, the sun doesn’t set in the summer. In the winter it’s the opposite; the sun doesn’t rise and the arctic circle experiences several months of total darkness. (How depressing.) But to answer your question, imagine shining a flashlight straight up and down on a table. The light “spot” would form a circle. The light energy is focused on the area of the circle. Now imagine tilting the flashlight and shining it on the table at an angle. The light “spot” would spread out and form an oval. The area of the oval would be greater than the area of the circle. With the same amount of light energy spread over a larger area, there is less energy per unit area. When the sun is the source of this light energy, the amount of energy received at different angles is referred to as “insolation”.

Imagine a flashlight shining on a table at different angles

Imagine a flashlight shining on a table at different angles

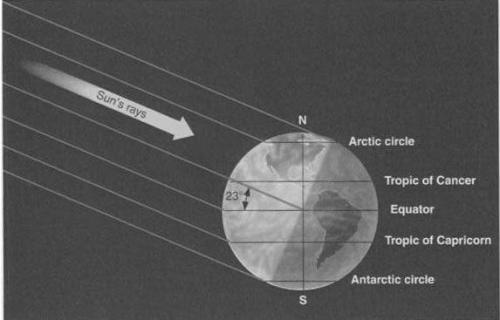

The sun shines straight up and down on the equator during the spring and fall equinoxes and at every location between the Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn at some time of the year. But outside of these latitudes, the sun always strikes the Earth at an angle because the Earth is tilted on its axis 23.26º. What this means is that the light received outside of the tropics is more spread out per unit area (like the flashlight) and it hits the Earth at the greatest angle at the poles. So, even though the sun is shining 24 hours a day, the amount of insolation at the poles is less and this contributes to the poles not heating up as much as they otherwise would.

The sun strikes the Tropic of Cancer at 90º on the Summer Solstice

The sun strikes the Tropic of Cancer at 90º on the Summer Solstice

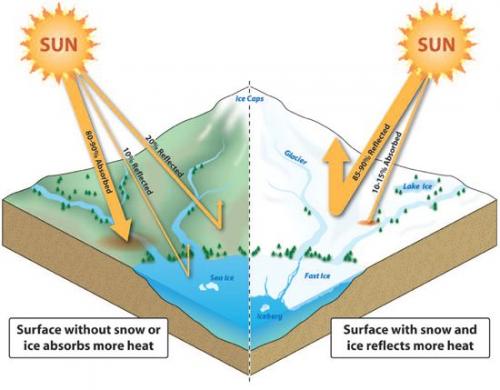

There is another factor at work here as well: albedo. Albedo measures the reflectivity of a surface. White surfaces reflect light and black surfaces absorb light. What color dominates at the poles? If you said white (snow fields, ice sheets) you are right. Much of the sun’s energy that hits the poles just bounces back off because of the high albedo at the poles. So, low insolation and high albedo combine to reduce the light energy and warming at the poles.

More sunlight is reflected at the poles due to the high albedo of the surface.

More sunlight is reflected at the poles due to the high albedo of the surface.

Comments