We’ve made it to the continental shelf of Antarctica! It’s freezing down here, literally. There’s a light snow falling outside. But no sea ice yet. Now that we're here we can get started with all the work! We’ve started working shifts (usually 12a-12pm or 12p-12a) to monitor the equipment around the clock. As we approached the continental shelf we turned on the multi-beam bathymeter to begin taking measurements of and mapping the ocean floor. I’ll be spending a lot of time working on this equipment over the next several weeks, so here’s a little more information about what it is and how it works.

E., 4th grade, requests we take a closer look at the equipment we use on the ship.

E., 4th grade, requests we take a closer look at the equipment we use on the ship.

A Closer Look at Multi-beam bathymetry

Bathymetry is the study of the underwater depth of ocean floors; it’s like underwater topography. Bathymetric charts show the terrain of the sea floor and can be used for navigation, science, and exploration.

In the past, ropes or cables were lowered off the side the boat to measure depth. Now scientists use “multi-beam” or “swath” echo-sounders. These machines send thousands of beams of sound out at different angles. This sound, usually 0.1 to 50 Hz depending on the water depth, bounces off the ground and returns to sensors on the boat. The time it takes for the sound to return can be used to calculate the depth of the ground. Other sensors on the boat correct for the boats movement to ensure accurate measurements. This data and the exact GPS locations of the soundings are compiled into a map.

A representation of how multi-beam bathymetry works from NOAA.

A representation of how multi-beam bathymetry works from NOAA.

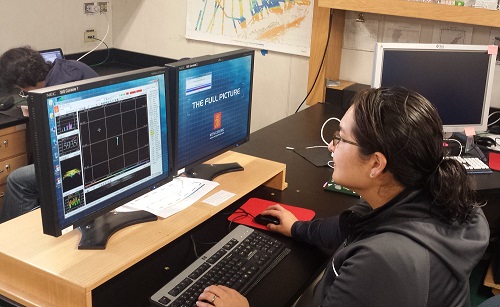

I can’t actually take a picture of the equipment as it’s under the ship, but here’s what the workstation where we manage the equipment looks like.

The station from which the multi-beam is controlled on the ship.

The station from which the multi-beam is controlled on the ship.

There is someone at the station 24 hours a day to ensure the multi-beam is working properly, making sure it is bouncing sound off the ocean floor (and not a piece of stray ice or something) and to make any adjustments to the sensors as needed. As you sit at the station, you can actually hear the “ping” made as the equipment sends sound out to the ocean floor echo around the room—it sounds like a dolphin trying to speak “baby bird.” During shifts we also “clean up” the data and get rid of sound distortion or sound points that bounced off incorrect things.

Right now I’m fairly new to all this, so I have a shorter shift, about 6pm-12am, with someone supervising me part of the time (thank goodness… I can ask lots of questions). I’m told I’ll get the hang of it very quickly. It’s nice because I get the “morning” of 12p-6p to help out with other data collection we’ll be starting soon.

Dominique Richardson works at the multi-beam computer station.

Dominique Richardson works at the multi-beam computer station.

Try it at home

Although scientists now use sound to measure depth, you can try your hand at bathymetry the old fashioned way. You’ll need: a friend or parent, play dough, a small box, tin foil, and a thin skewer longer than the box.

- Have a friend or parent make a simple shape out of play dough. Place this at the bottom of a small box and cover it tin-foil or a dark fabric (something you can’t see through, but you can poke a skewer through).

- Use the skewer to take “soundings”. Poke the skewer through the cloth or foil and measure how deep it goes. Be careful not to poke a hole in the dough. Try to take your soundings in a grid pattern for best results. You may wish to draw out a grid on your foil to help you decide where to take your soundings.

- Record your data and then draw a map of your “soundings” on paper, graph paper will work best. See if you can determine what shape was in the box (or create an accurate map of your “seafloor”).

For a more detailed version of this activity, check out one my fellow PolarTREC teacher’s lesson on bathymentry.

Comments