Grayling face! Photo by DJ Kast

The Why!

Grayling face! Photo by DJ Kast

The Why!

Effects of Climate change on the arctic fish

As the climate warms, the water (lakes and streams) warm, and the fish need to eat more food. The reason the fish need more food is because as it gets hotter, they get hungrier and need to consume more food to make up that energy. For example, if you are running on a hot day, you get tired more quickly. When you’re tired, you need to eat more food to keep going. It’s the same with the fish, they need more energy to swim, jump out of the water and then they need to eat more food.

The problem is that there may not be enough food for the fish as the climate and the water warm

The warming water has many different effects on each part of the food web. It affects the bacteria, the algae, the zooplankton (copepods), and insects that the fish are eating. Some of these organisms will adapt and do better in warmer water, and some won’t be able to adapt to the change and will do worse. What scientists are looking at with these fish is to understand how the changing climate affects each part of these groups within the food web.

The scientists here at Toolik are looking at each level of the food web to see if they are doing better or worse as the climate changes. That way they can see what food is available for the fish to eat.

Science Repeating PatternsWhen speaking with the fish researchers here at Toolik, I realized that they are thinking about fish the same way we are thinking about microbes. Both groups are studying biogeography! We are studying how microbe diversity varies across Arctic watersheds and the fish team is studying how fish diversity varies across Arctic watersheds. We are both interested in climate change and how it might alter connectivity across the landscape, but the microbe group is working with organisms that have much larger populations and much faster growth rates than fish.

The fish researchers are studying how Arctic Grayling might adapt to climate change and are using them as a model species for how other organisms will adjust to a changing climate. They are measuring how different populations move between river systems that have different temperatures and degrees of connectivity. The idea of connectivity thinks about where fish travel now and where they will go into the future if it gets wetter or drier. They are also looking at how movement of fish affects the genetic diversity and isolation across the Arctic freshwaters systems.

The who- Fish Research Team:- PI- Mark Urban (University of Connecticut) and Linda Deegan (Woods Hole, MBL)

- Project Coordinator: Cameron Mackenzie

- PhD/Postdoc: Heidi Golden

- Greg Hill, Tom Glass, Mary Kate Swenarton, Sarah Wassmund

They are a member of the trout and salmon family (Salmonids).

The dorsal fin of an Arctic Grayling. Photo by DJ Kast

The dorsal fin of an Arctic Grayling. Photo by DJ Kast

Grayling are a circumpolar species, which means that they live in Arctic regions throughout the world like Greenland, Canada, Alaska, and Russia. They have also been found in Montana. They live for long periods of time. The oldest one they found on this particular project was 24 years old.

Grayling are insectivores so they eat insects primarily. However, they also eat other things, including tundra voles (skeletons were found in their stomachs!!). They are crucial in Arctic food webs because they are a vital source of protein for larger fish species like Arctic Char and Lake Trout.

I caught another Lake Trout in Toolik Lake. This is what they look like! Photo by DJ Kast

I caught another Lake Trout in Toolik Lake. This is what they look like! Photo by DJ Kast

Greg Hill kisses a fish he caught. Photo by DJ Kast

The Where!

Greg Hill kisses a fish he caught. Photo by DJ Kast

The Where!

They are looking at 3 water systems that are different sizes, connectivity, and temperature regimes:

- Kuparuk River (largest)

- Oksrukuyik Creek (least well connected)

- I-minus Lake (coldest)

Fish tagging

The fish are tagged so that they can monitor fish traffic between streams and lakes. The PIT tags (Passive integrated transponders) act like Fastrac or EZpass transponders that you put in your car.

Pit tag in Tom's hand. Photo by DJ Kast

Pit tag in Tom's hand. Photo by DJ Kast

There is an antenna on each of the different rivers and the antenna acts like a tollbooth that reads the transponder and records the data (tag number, date, time, and how long they were in the area).

Tom Glass standing behind the solar panel that runs the fish traffic antenna. Photo by DJ Kast

Tom Glass standing behind the solar panel that runs the fish traffic antenna. Photo by DJ Kast

Antenna receiver and the wire that goes across the entire inlet of Toolik Lake. Photo by DJ Kast

Antenna receiver and the wire that goes across the entire inlet of Toolik Lake. Photo by DJ Kast

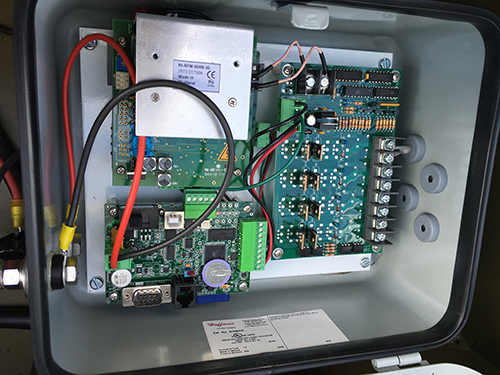

The Electronics of the Antenna, the programming and the SD card that stores all the fish data. Photo by DJ Kast

The Electronics of the Antenna, the programming and the SD card that stores all the fish data. Photo by DJ Kast

PIT tags are small electronic microchips in a glass tube so it doesn’t hurt the fish. It is similar to the microchip that the veterinarian puts into your dog. The chips let you see where they are, and in this case they let you see where they are in the river.

How to tag a fish:- Catch fish with fishing rods or “fyke nets” it’s a row of circular hoops with a lead net that trap fish so that they can’t escape!), weir (funnel fish into a trap).

- Place fish into a holding net.

The holding and recovery pen in the Toolik inlet. Photo by DJ Kast

The holding and recovery pen in the Toolik inlet. Photo by DJ Kast

- Use handheld PIT Reader to see if it has a tag already.

Reading the PIT tag of one of the Arctic Grayling. Photo by DJ Kast

Reading the PIT tag of one of the Arctic Grayling. Photo by DJ Kast

The PIT Tag reader used by the fish reserchers. Photo by DJ Kast

The PIT Tag reader used by the fish reserchers. Photo by DJ Kast

- If it does not, place the fish into the water that has an anesthetic in it called Aqui-s. This water/ Aqui-s concoction is used to safely anesthetize the fish for the fish tagging process essentially making it very sleepy so it won’t remember.

Fish in the bucket. Photo by DJ Kast

Fish in the bucket. Photo by DJ Kast

- An incision is made near their gut cavity with a scalpel

Incision on the grayling. Photo by DJ Kast

Incision on the grayling. Photo by DJ Kast

- A syringe is used to put a PIT tag into the incision (small size tag for juveniles and larger ones for adults). Then super glue is used to close the wound.

- Data is also collected on each fish.

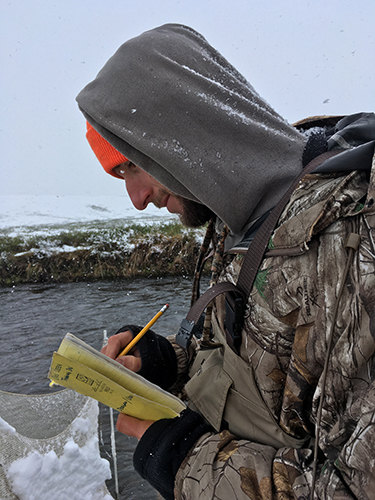

Greg Hill taking notes on the research data being collected on the Arctic Grayling. Photo by DJ Kast

Greg Hill taking notes on the research data being collected on the Arctic Grayling. Photo by DJ Kast

a. Length

Measuring the fish length. Photo by DJ Kast

Measuring the fish length. Photo by DJ Kast

b. Weight

How the Arctic Grayling are weighed in the field. Photo by DJ Kast

How the Arctic Grayling are weighed in the field. Photo by DJ Kast

c. Spawning condition

d. Sex (if possible)- if milting (male) or shooting eggs (female)

e. Clip little pieces of two of the fins and place in ethanol to preserve. These clippings give DNA information on the fish.

Clipping of the caudal and adipose fins of an Arctic Grayling. Photo by DJ Kast

Clipping of the caudal and adipose fins of an Arctic Grayling. Photo by DJ Kast

Fin Clipping in ethanol tube. Photo by DJ Kast

Fin Clipping in ethanol tube. Photo by DJ Kast

f. Deformities like fight scars or parasites 8. Put fish into the recovery pen (laundry basket) until they are no longer knocked out and then release them back into the water system so they can swim along their merry way.

Greg Hill fishing at Toolik Lake. Photo by DJ Kast

Greg Hill fishing at Toolik Lake. Photo by DJ Kast

Comments