Variables

All scientific experiments can ultimately be boiled down to two very concrete parts: the independent variable, or that which the experimenter manipulates (the treatment) and the dependent variable, or that which the experimenter collects data on (the result or response). In a lab, it is imperative that the experimenter eliminates as many confounding (or outside/other) variables as possible so that they can say with certainty that the outcome of the experiment was a direct result of the manipulated variable, as it is the only thing that differed from the control (comparison) group. For example, scientists make sure to control as many aspects of the lab as they can - make sure the lab is at constant temperature, all glassware is clean, precise measurements are used every time, gloves are used and not reused, timing is precise, etc. Most of the time, this is fairly easy for scientists to do - they use expensive technology, work in sterile environments and follow exact protocols. In the field, however, all bets are off.

Even a trace amount of soil on your shoes could seriously throw off the data collected in an experiment.

Even a trace amount of soil on your shoes could seriously throw off the data collected in an experiment.

The Five Ps

I often tell my students to remember the Five Ps when approaching any problem: Proper Preparation Prevents Poor Performance. Before scientists head out to the field, days and days are spent preparing for every possibility. Data sheets are printed, tools are packed and shipped, protocols are written and rewritten and fingers are crossed that nothing is forgotten, as most field work occurs in remote areas where it is difficult to get materials if you run out. Scientists are highly organized and efficient - their whole job is based in problem solving, so the best way to do that is to be prepared, have the ability to think quickly and prioritize. Those skills are necessary when the field (i.e. Mother Nature and other things beyond your control) decides to throw a monkey wrench into your Plan A. And Plan B. And let's be honest...plan Z.

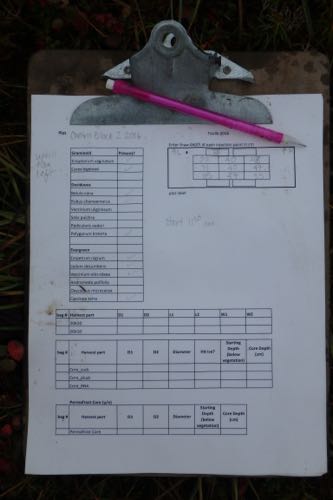

Becky’s meticulous data sheets (on waterproof paper) to record observations in the field.

Becky’s meticulous data sheets (on waterproof paper) to record observations in the field.

One of 4 coolers packed with some of the materials needed to remove soil cores from the tundra. The cores must be placed in coolers after harvesting to maintain their integrity.

One of 4 coolers packed with some of the materials needed to remove soil cores from the tundra. The cores must be placed in coolers after harvesting to maintain their integrity.

Science in the Field

So what happens when you show up to your field site only to learn that there are new variables that you could not have possibly anticipated? You adapt. When the research team arrived at Toolik, they found out that a key component of their experiment could possibly be highly compromised due to environmental conditions. Modifications to the original experiment had to be made on the fly (this is why scientists spend years of coursework developing rich content knowledge) – with only the materials packed and shipped ahead of time. Remember my last post – Toolik is in an extremely remote location. When the team needed a way to contain the experiment in the tundra, it was Becky’s preparation that saved us. Thank goodness Becky had shipped lots of extra plastic tarps – no need for fancy equipment here…

Dr. Lee Taylor installs a containment tarp in an experimental plot.

Dr. Lee Taylor installs a containment tarp in an experimental plot.

All materials must be hauled up the tundra boardwalk to the field site.

All materials must be hauled up the tundra boardwalk to the field site.

The Tundra Variable

Even when adjustments to the experimental plan have been made, there is still one variable that can be planned for but not predicted for – the tundra itself. The thawing tundra soil creates conditions that are different from one plot to the next, which means the same experiment can take 2 hours in one plot and 4 hours in the next one. Remember that every step of an experiment is done with precision and accuracy to make sure that there are no confounding variables. Protocols are constantly refined to deal with the soggy soil, foggy conditions, nearly frozen (or highly thawed) soil, malfunctioning equipment – well, you get the idea. At the end of the day (and the past 3 days seem to have been never ending), scientists will do what ever they need to do to make sure that their experiment runs in the most controlled way possible – even if that means working 12-14 hour days, skipping meals and just. getting. it. done. So what is “it” anyway? Stay tuned for next journal post, when I outline exactly what Team Deep Roots is doing out here.

It’s 9:15 pm and we are just heading back from the field. Lots of sunlight = lots more time to work in the field.

It’s 9:15 pm and we are just heading back from the field. Lots of sunlight = lots more time to work in the field.

Tundra Soil Video

Here’s a quick video I made in 2013 to show what slicing into the tundra soil is like. Make sure to listen for the squelch at the end.

Comments

Pagination