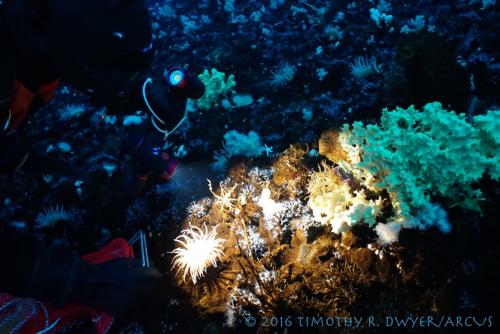

Scientific scuba divers use bright lights and cover lots of terrain in searching for pycnogonids to collect.

Scientific scuba divers use bright lights and cover lots of terrain in searching for pycnogonids to collect.

Scientific scuba diving is defined by US law as a special type of underwater work that supports scientific research. It is specifically set apart from recreational (aka, pleasure) diving and commercial diving (think underwater construction tasks, like welding). It allows researchers with the proper training to perform a variety of tasks, all under the supervision of a group of professionals that make up a scientific diving control board. This oversight keeps people safe, and throughout the US, scientific divers have far lower rates of injuries than both commercial and recreational scuba divers. So what are we actually doing while we're down there? The five researchers of Team Pycno are working on a number of different projects during the expedition and our diving supports the goals of each.

Dr. Amy Moran locates a sea spider and evaluates its condition before collecting it.

Dr. Amy Moran locates a sea spider and evaluates its condition before collecting it.

The main effort early on in our expedition has been to find and collect sea spiders for a number of different laboratory observations and experiments. With hundreds of different species found in the Antarctic, team members are hoping to collect a variety of individuals to compare to one another as well as a number of different sizes to compare within each species. Certain spider species are large and obvious, but others are smaller and cryptic. It takes a few dives to get good at spider hunting, but once the human brain develops a "search image" for sea spiders, they're much easier to pick out of a background rich with other invertebrates.

Most collections are done by hand with the animals placed into mesh bags for transport to the surface.

Most collections are done by hand with the animals placed into mesh bags for transport to the surface.

Some experiments are better performed in the natural environment than in a lab. Dr. Bret Tobalske studies the way fluids move around animal bodies, as well as the ways the animals change shape to handle their fluid environment. He spends time underwater simulating currents and filming pycnogonids that are exposed to this waterflow, observing their various postures and other behaviors. Dr. Tobalske also sets up trials where he encourages the animals to walk away from a central location, filming their gates so he can answer questions about the relationships between animal size and speed. Video is a useful way to record data because it allows the researchers to bring information back to the lab and review it repeatedly. But it doesn't entirely make up for the fact that we can only visit the under-ice environment briefly.

Dr. Bret Tobalske tracks a spider that has been dislodged during a current flow trial.

Dr. Bret Tobalske tracks a spider that has been dislodged during a current flow trial.

Our study subjects live in the ocean for far longer periods of time than our 30-40 minute dives. To account for this, researchers deploy instruments that continuously measure aspects of the physical environment while we're away. It's not the same as being there, but these instruments give valuable information on light levels, current flow rates, dissolved oxygen concentrations, and more. And they can stay down in places and for periods of time that divers could never hope to. Setting up and recovering this equipment is another aspect of what we're doing underwater and helps paint a more complete picture about the environment in which gigantism persists.

Rob Robbins prepares to recover an S4 current meter (the yellow ball at the bottom of the frame) after 11 months of data logging on the seafloor.

Rob Robbins prepares to recover an S4 current meter (the yellow ball at the bottom of the frame) after 11 months of data logging on the seafloor.

Comments