My working hours are pretty evenly divided between diving with the team and running a sea spider physiology experiment in one of the Crary lab's "environmental" rooms. Environmental rooms are small sealed chambers that allow researchers and engineers to conduct experiments and tests under stable conditions. The range of abiotic variables that can be controlled typically include temperature, humidity, light, and atmospheric pressure, all of which may have influence over the behavior of the organism or material being tested.

The Crary Laboratory has four environmental chambers that can vary a number of different physical conditions. This one is ours.

The Crary Laboratory has four environmental chambers that can vary a number of different physical conditions. This one is ours.

I'm working with sea spiders who spend their lives in McMurdo Sound, which remains below freezing for months on end and sees only minor temperature changes over the course of a year. To keep the sea spiders happy while we vary other water chemistry characteristics and measure the animals' responses, all of the tests need to be performed in water at McMurdo Sound temperature (29F/-2C). While the Crary Lab is equipped with a flow-through sea water system through which water is pumped directly from McMurdo Sound, the water temperature fluctuates as it makes its way from the ocean through the outdoor pipes and eventually into the warm lab building. Hence, our need for an environmental room, which is kept at a brisk (29F/-2C).

-02C. A few degrees below freezing.

-02C. A few degrees below freezing.

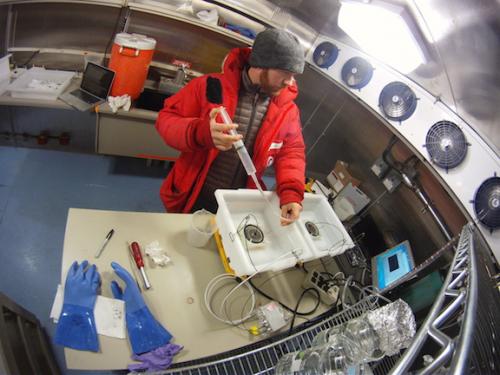

For a few hours every other day or so, I set up, manipulate, and break down 12-hour-long runs of our experiment while standing in what is basically a walk-in freezer. The cold air itself - circulated through the room by large fans high up on one wall - is not a problem to deal with. After all, it's a couple of dozen degrees warmer than the outside temperature and I am well equipped with cold weather gear (Big Red gets worn indoors, too). The real challenge is having my bare hands in the icy water. Through most of the process of setting up our experimental apparatus, I wear big blue fisherman's gloves. However, occasionally I need the dexterity of my gloveless fingers to tighten a tiny knob, insert an optode, or perform some other precision-required task and it doesn't take very long for the water baths to draw the heat from my fingers. If I let it progress, the experience evolves from discomfort, to a stinging pain, to numbness, to loss of finger function. After the first experimental trial, I wisened up pretty quickly and now I'm quick to take breaks once my fingers start to tingle. So what's making me risk finger pain and numbness? The oxygen hypothesis for polar gigantism, of course.

Manipulating oxygen levels in our experiment. Big Red gets some use indoors.

Manipulating oxygen levels in our experiment. Big Red gets some use indoors.

Comments