Caution Warning

This blog post discusses a seminar held on Field Safety and contains mentions of fake blood and theoretical injuries. Rest assured that all members of my team are physically safe here at Toolik!

Slow is Smooth, Smooth is Fast

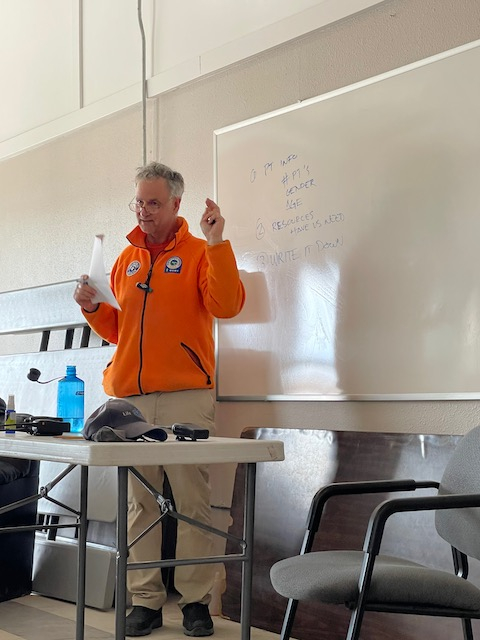

Last night, our field station EMT, Dennis, held a seminar on Field Safety. The field station does not have a hospital or any major medical equipment, so in critical situations Dennis’s primary job is to stabilize any patients for transfer to facilities elsewhere. Because of the limits of what care Dennis is able to provide at Toolik, it’s very important to be able to decide what is considered “critical” and what isn’t.

With that being said, Dennis started out the seminar with a field trip to an outdoor location where he had poured an unknown amount of [fake] blood (made with water, three drops of red food coloring, and four pumps of ketchup, he told us later) on the ground and asked us to estimate how much blood we thought there was. Dennis pointed out that in this situation it might be extra difficult to estimate because some of the blood had absorbed into the ground.

Dennis asks us to guess how much fake blood is present?

Dennis asks us to guess how much fake blood is present?

It turned out that this represented 0.5 L of blood. Now, the question became, is this a critical condition? The group was definitely divided on this question, but I think overall, we decided it wasn’t critical. The question then became, how much blood loss is considered critical? If we got to 1 L, was that critical?

Dennis explained that the average adult human contains 5 L of blood (a bigger person may have 6, a smaller might have 4), and after 14% (or 0.7 L) blood loss, that person will start to feel adverse side effects.

After the demo got us thinking about field safety and critical conditions, we went back inside for the main focus of our lesson, which was all about making the call.

Making the Call

Imagine you’re taking a walk and you trip and fall, your ankle twisting in the process. You hear a loud crack. When you try to get up, you find you can’t put any weight on your leg, and you need help. What do you do?

If you’re in the city, you probably just call someone you know and explain what happened and stay on the phone with them until they show up. You might even be able to send a map of your location to them so they can find you easily.

Unfortunately, for researchers in the Arctic, phone service is a luxury, and most of us don’t have it when we’re in remote locations in the field. Instead, people carry satellite phones and radios that don’t rely on networks in order to work. But even those are uncertain in these situations, which means you should only truly count on having a single one-minute transmission to whomever is listening. What details do you include on the call?

The Details

Here are the details Dennis told us to include on all calls if we were ever in this situation (or if we were in a situation where someone else fell ill in the field):

- The number of patients, their genders, and their age

- The number of responders present (aka how many people are there who are not hurt or injured)

- A brief description of what the injury is and/or what occurred

- The location

- A description of the weather

These are also the details that Dennis told us that we should write down before we even get on the call so that we make sure not to leave anything out.

"Write it down!"

"Write it down!"

Practice

Dennis had a great structure to his lesson, because after an engaging hook, and a short mini-lesson, Dennis had volunteers act as “patients”, “responders”, and “receivers” (those back at camp listening to the call). The responders were given two minutes to ask questions of the patient (who had been given all their relevant information by Dennis before they began) and write down all the relevant information, and then one minute to make the radio call to the receiver, who then relayed the information back to all of us.

Jesse, one of the receivers, relaying back the information he learned from one of the responders over the walkie.

Jesse, one of the receivers, relaying back the information he learned from one of the responders over the walkie.

At the end of each scenario, we also discussed what might happen afterwards… Do you send the helicopter out? Does this person need to go to Prudhoe Bay or Fairbanks for more intensive medical care? Sometimes the answers felt a little surprising, but in the end, all made sense.

The key phrase

Throughout the process, Dennis reminded us of his favorite phrase, “Slow is smooth, smooth is fast”. It feels counterintuitive the first time you hear it, because everyone knows that time is key in critical situations. But, as he reminded us, if you forget something or leave something out, it could make a bigger difference in the end. “Slow it down, write it down before you call, remember… slow is smooth, smooth is fast”.

Reminder! Upcoming: PolarConnect

Next week, I will be hosting PolarConnect – a live virtual event in which you can join me and my team as we discuss the science we’ve been working on over the past few weeks and then answer any questions you have about the experiences of completing field work in such a remote location!

The event will be held on Tuesday, June 15th at 10 a.m. Alaska Time (11 a.m. Pacific, 12 p.m. Mountain, 1 p.m. Central, 2 p.m. Eastern), and will last for roughly an hour. Anyone and everyone is welcome to join by clicking on the registration link below. Once you have registered, information regarding the event (like the zoom link!) will be sent to your email.

Please share with your networks and join us in expanding the accessibility of Arctic science!

Comments

Add new comment