Data Collection, Full Steam Ahead

The past two days have been productive days with our data collection. We made several CTD casts and water collection. Sometime in the next few days we will discuss more about how the CTD works and why it is important for our research questions.

Driving the boat towards the fjord for a productive day of data collection.

Driving the boat towards the fjord for a productive day of data collection.

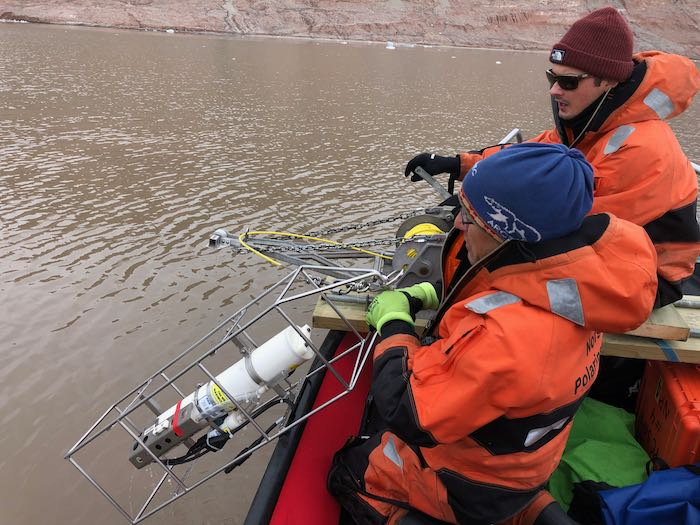

Xander and Mark getting the CTD ready to lower into the ocean.

Xander and Mark getting the CTD ready to lower into the ocean.

We need to collect water samples so that we can calibrate the turbidity sensor on the CTD instrument (turbidity is a measure of how cloudy the water is, because of the sediment carried from the glacier into the water). Basically, the CTD uses an optical process called “optical backscattering” to measure the turbidity. We need to make sure that the optical process matches the amount of sediment in the water. So, we need to collect water samples and filter out all the water to measure the sediment left behind. (More on this in a future post.)

Julie instructing us in the proper method for filtering water for turbidity calibration.

Julie instructing us in the proper method for filtering water for turbidity calibration.

Xander monitoring the device which filters out sediment from the water using a small vacuum pump.

Xander monitoring the device which filters out sediment from the water using a small vacuum pump.

Since our velocity meter doesn’t seem to be a useful tool for this field study, Julie decided to use an old technology - a drogue to measure the speed and direction of the water coming off the glacier. It sort of looks like a little sail; you attach a buoy to the top and a weight to the bottom. You drop it in the water, mark the GPS location and the time. Then you wait several minutes and pick the drogue up. From the starting and ending position, and the time it took to get there, you can get a decent measurement of the water velocity at that location. I love how low-tech this is, at the same time we are using seriously high tech devices!

Julie showing off the drogue she made back in 2011.

Julie showing off the drogue she made back in 2011.

Xander dropping the drogue. About 15 minutes later he picked it up using a boat hook.

Xander dropping the drogue. About 15 minutes later he picked it up using a boat hook.

More Drone Flights

I also had a chance to do several drone flights. Flying the drone over the glacier is an amazing experience - these are places that would be much too dangerous or even impossible to get to. As the drone pilot, I was able to guide the drone incredibly close to the glacier face, and go over the top and explore the surface. I even got down close to a wide crevasse (one of the cracks that form as glaciers move across the landscape)!

Here I am flying the drone using my ipad to monitor the flight. In the upper left of the photo you can just make out the drone.

Here I am flying the drone using my ipad to monitor the flight. In the upper left of the photo you can just make out the drone.

Xander makes another expert catch of the drone. Flying from a moving boat is a bit of a challenge!

Xander makes another expert catch of the drone. Flying from a moving boat is a bit of a challenge!

[Here is a fun video](

) I put together from a few drone flights. I had fun adding music to it as well!

The drone flying will also be very useful as we investigate what is happening to the upwelling plumes - where water comes gushing out from under the glacier. We are able to see details of how the water flows out from the glacier. For example, as you watch the videos, you’ll notice how incredibly brown the water is - this is from the sediment being carried by the glacier. Differences in the shades of brown, along with observing where the icebergs are, can give us information about how forceful the water is coming off the glacier.

[Here is a video I took](

) looking down along the edge of the Kronebreen Glacier. I’m hoping to duplicate this flight a few times over the next few weeks to help visualize what short-term changes are occurring to the glacier. I am also hoping to do something similar at an adjacent glacier (the Kongsvegen Glacier).

Some Setbacks Remain…

Kelly has been working so hard to get the bathymetry equipment up and running. There have been a series of roadblocks and challenges. I am incredibly impressed at her perseverance! Today she seemed to have a breakthrough, and we’re crossing our fingers that it will be up and running tomorrow.

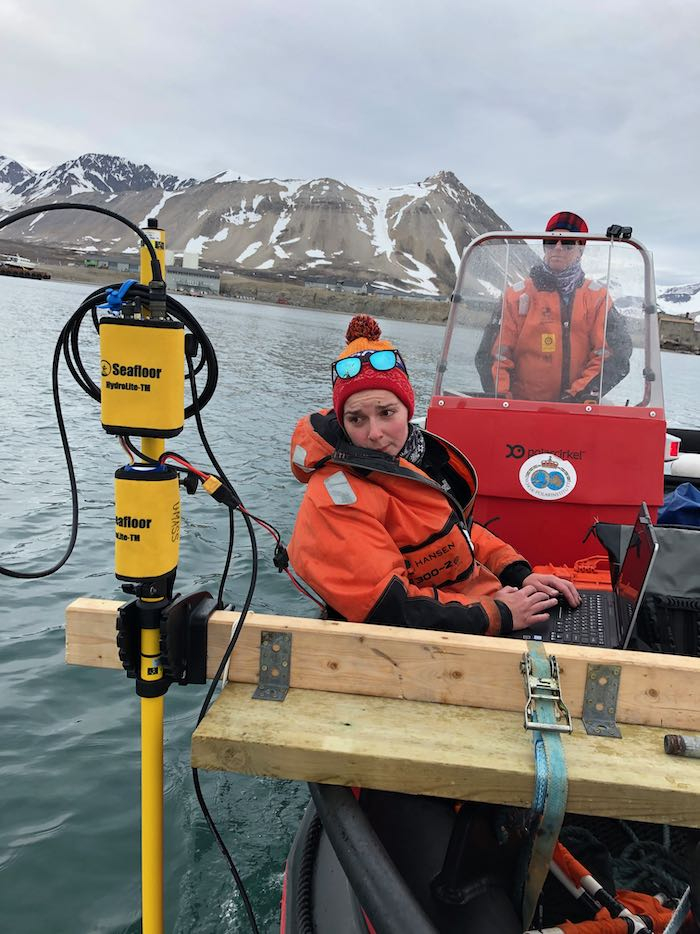

Kelly setting up the bathymetry equipment for today’s test.

Kelly setting up the bathymetry equipment for today’s test.

Kelly monitoring the bathymetry equipment as she conducts today’s test.

Kelly monitoring the bathymetry equipment as she conducts today’s test.

All of the challenges Kelly is facing are made more difficult because of how remote we are. In addition, we are also in a radio silent area, which means that we can’t use radio signals for the different parts of the device. This is a radio silent area because NASA and a group from Germany are doing high level experiments using radio telescopes. Any radio waves will interfere with these experiments. Therefore, any use of radio waves is forbidden in Ny Ålesund. This means no WiFi or bluetooth! All our devices must be in airplane mode.

We often don’t think about how all of our devices communicate with each other. Our phones and computers communicate with WiFi and bluetooth signals - these are all radio wave signals that we take for granted. I am communicating to you through ethernet - a direct wired connection to the internet. In fact, I had to get special permission to fly the drone - and I can only do so during specific times when the radio wave experiments are not being conducted.

So what is a glacier anyway, and what do they leave behind?

This whole research project is about glaciers, so I figured I'd take the time to go over some basics about what glaciers are, and what you can tell about a glacier from the stuff it leaves behind.

So what is a glacier, anyway? A glacier is a large mass of ice that stays frozen the whole year. The ice in a glacier is constantly flowing. It flows for a very simple reason – gravity! Gravity will pull the ice that is at a higher elevation down to lower elevations. Of course, it flows very slowly, way too slowly to see, but some glaciers can move many meters a day. Kronebreen Glacier, one of the ones we are studying, flows at about 1-2 meters (3-6 feet) a day.

One of the things that geologists can study is called the Mass Balance of the glacier. The mass balance compares how much new snow and ice is added to the glacier to the amount it is losing mass through melting (or icebergs). If the mass balance is zero, that means that the glacier loses the same amount of mass as it gains. In that case, the glacier will not be receding. However, most of the glaciers in this area are receding, which means that they are melting much faster than new snow and ice is added. This is due to global warming.

What's important to remember is that all of the debris that is in and on the glacier moves with the glacier, until the ice that it is on melts away.

At the edge of a glacier, the ice either falls off into the sea (in a tidewater glacier) or, if it is on land, the glacier will end in meltwater. Either way, whatever the glacier was carrying is deposited out.

Notice how brown the water is in front of the glacier. This is because of all the sediment flowing out.

Notice how brown the water is in front of the glacier. This is because of all the sediment flowing out.

Notice how much sediment this iceberg is carrying!

Notice how much sediment this iceberg is carrying!

Glaciers are Dynamic!

One of the things that is so obvious when you spend time in front of a glacier, as we have all week, is how dynamic they are. Today we spent many hours in front of the glacier and the whole day you could hear booming and cracking as ice was shifting and moving. Every once in a while we would see icebergs calving off the glacier (calving is the term used when new icebergs fall off a glacier). This experience makes it super obvious how much the glacier is moving and changing.

Here is a video I compiled of some of the calving events we witnessed today. It’s hard to capture these events as you might imagine; you have to be ready with the camera! Just to get some perspective, all of these events happened in less than an hour.

Julie takes a well-deserved rest on the way home after a productive day of data collection.

Julie takes a well-deserved rest on the way home after a productive day of data collection.

Comments

Add new comment