Flying Off the Map

Mission control: "Data - Are we going to fly off the map today?" We've all found ourselves without a map when we need one, but this is different. We headed to the South Pole today to run a baseline flight of highest priority. This is a first trip to the pole for the year and the data will be useful to many scientists working on different projects near the pole. It took about 5 hours to reach the pole, about 2 hours to collect our data, and about 5 hours back. Thank goodness we fly in the coolest plane in the sky!

This amazing plane holds up to 45 scientists and crew, flies for 12 hours and returns to where it started everyday. It's a real workhorse!

This amazing plane holds up to 45 scientists and crew, flies for 12 hours and returns to where it started everyday. It's a real workhorse!

Mapping the South Pole

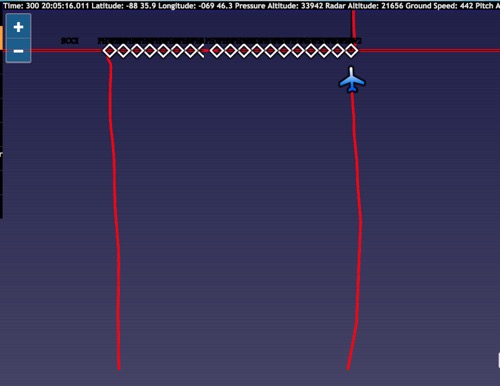

The map view was very peculiar near the pole as you might imagine. Here are some images that I collected as we approached.

Traveling down 70* Longitude, and turning to travel 180* along latitude 88* S appears as a line on the map, then shows us heading off the map, and then back on!

Traveling down 70* Longitude, and turning to travel 180* along latitude 88* S appears as a line on the map, then shows us heading off the map, and then back on!

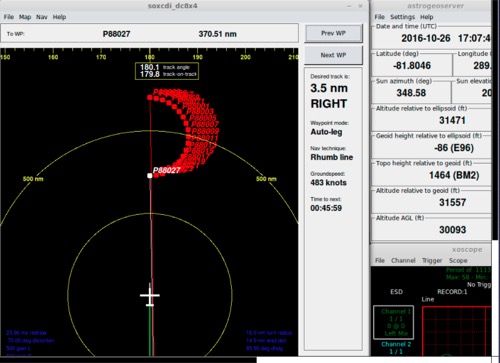

Our flight path shows the semicircle where the scientists collected data, 120 miles away from the pole. (NASA DC-Data Display System).

Our flight path shows the semicircle where the scientists collected data, 120 miles away from the pole. (NASA DC-Data Display System).

Notice that we leave the map; the image ends at 85 degrees S presumably because map projections become confusing past that, so when we did our semicircular flight along the 88S degree latitude line, it appears as a curve from "below" but a straight westerly path on the projection. When we had completed 180 degree rotation and aligned with 70E longitude, we traveled toward the pole. This path was flown at 1000’ altitude, while scientists on board collected data. We then ascended to much higher altitude and traveled toward the pole south along the 70 degree E line to the South Pole.

Our amazing navigator, Navy Commander Walter Klein keeping us on track.

Our amazing navigator, Navy Commander Walter Klein keeping us on track.

At the Pole

Flying low elevation above South Pole was avoided because of operations at South Pole Station, an American science base there. The south pole area has a good deal of radio frequency interference (RFI), has protected clean air space to the northeast, and several radio telescopes that we don't want to disrupt. So, as we approach we turned off our instruments (lasers and radar) 40 miles prior to passing overhead. South Pole Station is 12,000’ above sea level and is located in the most extremely remote place I have ever seen. It is thrilling to cross the South Pole, even for veteran mission command personnel. What an experience!

View of South Pole Station as we cross the Pole (DC-8 Downward Facing Camera).

View of South Pole Station as we cross the Pole (DC-8 Downward Facing Camera).

Photo of the DC-8 from scientists at the South Pole! Yeah, we are in that plane!

Photo of the DC-8 from scientists at the South Pole! Yeah, we are in that plane!

Taking pictures of the instruments when we got to 90 degrees south was fun for everyone!

Taking pictures of the instruments when we got to 90 degrees south was fun for everyone!

The Polar highlands are extremely thick ice unobstructed by the wind. On the surface are snow features up to a meter high, and several meters long, that are essentially snow waves. With the prevailing wind generally easterly from the higher ground, the snow waves (sastrugi in Russian) at South Pole are the dominant texture on the ice surface. Below the ice, thousands of feet of layers of ice show a long history of snow accumulation.

The ice at South Pole is over 12,000' thick, snowy and windy.

The ice at South Pole is over 12,000' thick, snowy and windy.

Our Long Commute

During our many hours of downtime, we entertain ourselves with various activities: classroom chats through XCHAT, reading, playing games, sleeping, discussions, and on the hour, some pushups! Having enough gas is always an area of concern. Fuel supply is calculated carefully so that there is enough fuel not only to get back to Punta Arenas but also to get 200 miles farther north to Balmeceda, Chile, in case our regular landing area is not available or there is severe weather at Punta Arenas. Even with this extra allowance, it is always very close. One pilot stated that we had a “thimble full” of extra fuel on board. While I hope that is a large thimble, I greatly admire the level of mathematics involved in the myriad of calculations necessary to make safe flights in extremely remote areas.

Staring out the window at the vast landscape is captivating

Staring out the window at the vast landscape is captivating

Amy FitzGerrell (NSIDC) learning about navigating through tones in the headsets with NASA scientist John Sonntag.

Amy FitzGerrell (NSIDC) learning about navigating through tones in the headsets with NASA scientist John Sonntag.

Comments