Calving Fronts are Amazing Places

The Pine Island Glacier, or PIG, is 68,000 square miles, or roughly the size of Oklahoma. It is Antarctica's leading source of melt water, leading to 0.11 mm per year sea level rise for at least the last 45 years. Pine Island Glacier is also the fastest moving glacier on Antarctica, its shelf sprinting 4-5 km per year between its grounding line and the Amundsen Sea. Stretched and thinned, this glacier exhibits extraordinary crevasse structures near its calving front.

The surface of the ice near the calving front of Pine Island Glacier is rough and cracked from being stretched.

The surface of the ice near the calving front of Pine Island Glacier is rough and cracked from being stretched.

The shapes of crevasses sometimes show geometric stresses.

The shapes of crevasses sometimes show geometric stresses.

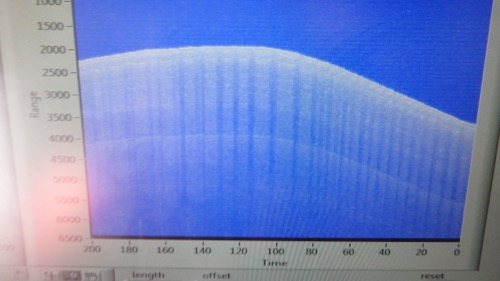

The Snow Radar shows the crevasse field as vertical cracks clearly.

The Snow Radar shows the crevasse field as vertical cracks clearly.

The shallow sea basin upon which PIG finds itself, allows rapid melting of the glacial ice from below. Ice streams such as PIG that lead to ice shelves are deteriorating rapidly. This glacier has been studied with radar and laser for 14 years, one of the longest timeframes for this kind of data recording on Antarctica.

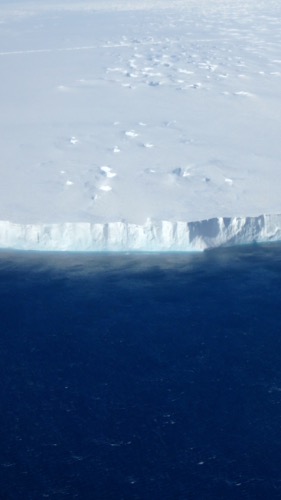

Pine Island Glacier calving front (approx. 200 feet high).

Pine Island Glacier calving front (approx. 200 feet high).

The crevasse shapes and colors are stunning!

The crevasse shapes and colors are stunning!

Western Antarctica is a Snowy Place

On our approach to the target area, we were a bit confused by the hazy look of the atmosphere. Not sure if we were seeing low lying clouds that had not been on our weather radar this morning, so we continued ahead cautiously. And then we knew, it was blowing snow! Although this was only my 7th flight with Operation IceBridge, I had not seen this before. That fact isn't actually surprising. Most of Antarctica is a desert because very little snow falls here, partially because the air is so cold, it cannot hold much moisture. How do we wind up with thousands of feet of ice then? The low temperatures ensure that what does fall, stays here. The snowiest part of the continent is where we are going today, so the blowing snow makes sense. The snow distribution is caused by weather patterns roaring off the Pacific Ocean and dumping snow along the Pacific coast, building glaciers. The dry winds then circle around on themselves, flowing down from the north, leaving the rest of Antarctica without much snowfall.

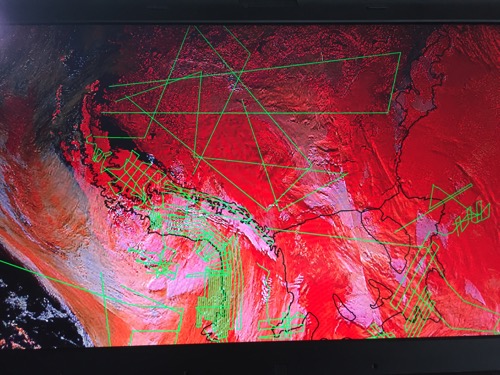

We study the weather maps carefully before choosing a flight plan.

We study the weather maps carefully before choosing a flight plan.

Thin layers of "Frazil" ice form with currents on the ocean.

Thin layers of "Frazil" ice form with currents on the ocean.

The shapes and colors of the uneven surface is endlessly interesting.

The shapes and colors of the uneven surface is endlessly interesting.

A cold, dry dessert occupies the Dry Valley's west of McMurdo. The conditions there are caused by being bounded by mountains that draw what moisture is available out before the air masses reach the area, and by katabatic winds. These occur when cold, dense air rolls down off a high, cold area. The winds can reach speeds of 320 kilometres per hour (200 mph). As they come downslope, they get warmer and evaporate all water, ice, and snow in the area.

Dr. Peter Neff from University of Rochester takes photos of the beauty outside.

Dr. Peter Neff from University of Rochester takes photos of the beauty outside.

Comments