It dropped to about 40 degrees Fahrenheit last night, and the sound of a steady rain on my tent made it especially difficult for me to get out of my sleeping bag this morning. After a cup of Toolik Turbo (we don't have decaf., just "regular" and "high-test" coffee) Kiki and I put our rain gear back on for a trip up the hill. The weather isn't particularly ideal for spider activity, but we still have work to do.

A little tundra yoga in my rain gear.

A little tundra yoga in my rain gear.

Amanda met us on our way back in to ask if I would be interested in going to help trap squirrels and pick up our sample cups at the Atigun field site. I met Michael Sheriff at the International Polar Year Conference in Montreal. I asked if I could join him in the field within minutes of learning what he does. Michael is a Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Institute of Arctic Biology, University of Alaska Fairbanks. The video below gives a brief introduction to the talk he gave at the conference.

http://youtu.be/1jvx8yqBK2o

We were headed to one of Michael's three field sites called the Point. We drove to the Atigun River, and hiked along the banks to a boat that is more accurately described as a pool toy with half of a toy paddle. I crossed first while Michael held onto a rope connected to the boat so that he could pull it back to get himself across the river. Once we were on the little island, we had one more small paddle to a sand bank on the Point.

Our trusty boat???

Our trusty boat???

Michael Sheriff paddling across the Atigun River.

Michael Sheriff paddling across the Atigun River.

Michael pulling the boat back across the river.

Michael pulling the boat back across the river.

Like everything else in the Atigun valley, the point looks like a postcard. I immediately noticed that we weren't the first visitors to this beach as the sand was littered with tracks from caribou, fox, squirrels, and a wolf.

Wolf track at the Point

Wolf track at the Point

Our boat on the banks of the Atigun River waiting for our return.

Our boat on the banks of the Atigun River waiting for our return.

Our task today was to tag and recapture Arctic Ground Squirrels, or "sik siks." to determine population density. We first had to set out 75 traps on Michael's grid. Each trap is placed at a predetermined location, spaced about 40 meters apart from each other. We first found a stable place on the ground for each trap as the squirrels will tend to abandon a trap they sense is unstable. We then peeled four strips off a fresh carrot and place one in the opening of the trap, one on the platform that triggers the trap, and two towards the back. We had to be sure to place each piece of bait towards the middle of the trap so the clever squirrels won't just pull them out from outside the trap. With all 75 traps set we sat on the river bank to wait 90 minutes before checking them. We spent a lot of that time talking about ideas for science outreach to improve the connection between scientists and the classroom.

A trap waiting for a hungry squirrel.

A trap waiting for a hungry squirrel.

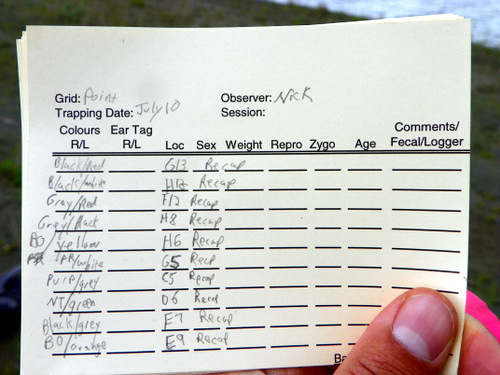

The data we were collecting today is based on the basic mark and recapture technique that is taught in every ecology class. The idea is that the smaller the population, the more recaptures you will have. You can estimate population size by multiplying the total number of individuals you have previously tagged by the total number caught and divide that product by the total number of recaptures. Michael's uses a much more complex computer model for his data that takes several factors into account, including location of capture among other variables.

I was thrilled to see our first squirrel at the third trap we checked! Most of the squirrels we caught were "recaptures," meaning that Michael had previously caught and tagged them. A series of colored tags are easy to spot on the ears of the recaptured squirrels. We record the squirrel's unique tag identification and the location of capture. Releasing them is as simple as opening the trap and letting them run free. Most run out immediately, but you do have to put your face down next to the cage to encourage others to leave.

Our first catch of the day!

Our first catch of the day!

This one has been previously captured. Notice the blue and orange tags in his ear.

This one has been previously captured. Notice the blue and orange tags in his ear.

New captures require a bit more time to process. Each squirrel is released into a mesh bag where it is weighed. Weighing a squirrel in a bag is trickier than I thought since the squirrels rarely stop moving while in the bag. Michael then measures the zygomatic arch (basically cheek bones) of the squirrel as an estimate of body size. A unique tag is then placed in the ear of each squirrel, gender is determined, data is recorded, and they are released.

Michael Sheriff bagging a captured squirrel.

Michael Sheriff bagging a captured squirrel.

Michael patiently waiting for a squirrel to stop moving so that the weight can be recorded.

Michael patiently waiting for a squirrel to stop moving so that the weight can be recorded.

Michael measuring the zygomatic arch.

Michael measuring the zygomatic arch.

http://youtu.be/0EkXMemUdRw

We caught a total of 34 squirrels in 75 traps on just one run! Only 5 of those were not recaptures. Normally Michael would reset these traps a few more times, but the weather got us off to a late start, and we still had to go pick up spider density pitfall traps. Squirrels can't be trapped in the rain because the exposure can drop their temperature to dangerous levels. We left the traps in place for tomorrow, but carefully closed all of them so that no squirrels would be captured when we weren't there to release them.

A little one!

A little one!

My data card full of recaptures.

My data card full of recaptures.

Science is fun!