I originally spoke to PhD student Shannan Sweet over a month ago about heading into the field with Team Bird, but we've had trouble working out compatible schedules. So I was excited to learn that we would be able to fit in an outing during my last week at Toolik! We drove out to the Imnavait Creek Research Site and followed a boardwalk that extended 100 meters into the tundra. The group is wrapping up its field season, so Shannan wanted start packing up and take the bear fence protecting their recording equipment down. The bear fence is an electric fence that protects equipment that records audio and weather observations. The whole system is powered by solar-charged batteries. It is intended to collect audio of birds in the area at set intervals, but it is sensitive enough to record mosquitoes buzzing.

Shannan Sweet taking down a bear fence.

Shannan Sweet taking down a bear fence.

Audio observation equipment with photovoltaic panels.

Audio observation equipment with photovoltaic panels.

The project is another wide-range 5 year study that looks at a number of factors including bird nesting success, bird stress responses, bird range expansion, and arctic shrub expansion. Shrub expansion in the arctic is a big topic studied by many groups. Basically as the arctic has warmed, shrubs are expanding in geographic range and size, outcompeting grasses and changing the ecosystem. This impacts changes to nutrient availability, snow pack, habitat, food webs, and many other factors. This project is so broad in scope that it involves three Principal Investigators from three different universities!

Caribou in the mist.

Caribou in the mist.

Soil

While looking up for a break in the weather, I did see a caribou emerging from the mist as it ran across a hill top. It was too rainy while we were at the Imnavait site to work with birds, but we still needed to take measurements of soil moisture and temperature in addition to measuring the depth of the active layer. The active layer refers to the thawed portion of the ground that sits atop the permafrost. Basically you take a long metal pole with handles and push it into the ground as far as you can before hitting the solid permafrost. You then read the length of the pole that went below ground. These measurements had to be taken every 10 meters along 4 forty-foot long boardwalks. Two of the boardwalks are located in shrub tundra, and two are in open tundra (few to no shrubs). The depth of the active layer varied significantly between the two types of tundra. It was very shallow in the open areas (averaging approximately 9 inches deep). It was consistently deeper in shrub tundra (averaging approximately 19 inches deep). Part of the explanation for this difference is that extra snowpack around shrubs insulate the ground below. This will not only have an effect on soil temperature, but an effect on the activity of decomposers and other soil organisms.

Jonathan Perez and Adam Formica collecting soil data.

Jonathan Perez and Adam Formica collecting soil data.

We got a brief break from the rain when we drove to our second sight of the day. This site is located near the Sagavanirktok River roughly 20 miles north of Toolik. The shrubs here are much taller, and the active layer of the soil is much thicker than at the Imnavait site. The soil has a much more clay-like consistency here, so pushing the probe into the ground far enough to reach the ice is much more difficult. The active layer depths here reach almost 3 feet!

Nick LaFave measuring the depth of the active layer.

Nick LaFave measuring the depth of the active layer.

Plants

This Sagavanirktok had some beautiful plant life in bloom, including Monkshood and Fire Weed (pictures below). Both flowers have interesting names. The Monkshood droops down to give the appearance of a monk's hood. Fireweed colonizes quickly, especially in areas that have been disrupted by disturbances like fire. I've been watching the blueberries at Toolik for weeks and wasn't expecting them to ripen before I leave. I was especially excited that the blueberries at this site were ripe and delicious! There is nothing quite like standing in the tundra eating blueberries off the bush, even if it involves swatting mosquitoes in the rain.

Monkshood

Monkshood

Fireweed

Fireweed

A single, perfect blueberry. Yum!

A single, perfect blueberry. Yum!

Bird Nests

Shannan is a PhD student at Columbia University. She spends a lot of time observing plant communities and on the seemingly impossible task of locating bird nests in the tundra. Shannan took me to see the nest of a White-crowned Sparrow hiding in a shrub. Even with tags to identify the location we had trouble finding it, so I was not surprised that it is difficult to see in my photos. The team spends hours watching areas that birds continuously return to, then take to the painstaking task of searching the shrubs for the nearly undetectable nests. Shannan identifies each nest based on location, nest materials, and a lot of other factors. She records a number of observations to compare the reproductive success of different birds based on nest location. Shrub expansion is also important to the study of the two bird species this group looks at. Lapland Longspurs nest in the side of tussocks on the open tundra, and range north all the way to Prudhoe Bay. White-crowned Sparrows nest in shrubs, and don't live as far north because shrubs become less common as latitude increases in the tundra. As shrubs expand northward, we might expect to see a northward expansion of the White-crowned Sparrow's range.

Can you spot the bird's nest in the middle of this picture? Imagine searching for these out on the open tundra.

Can you spot the bird's nest in the middle of this picture? Imagine searching for these out on the open tundra.

Insects

Ashley Asmus is a PhD student from the University of Texas at Arlington. She studies the insects that are part of this study. One cool aspect of this study is that it looks at multiple trophic (feeding/energy) levels. In addition to collecting arthropods in pitfall traps like we do with our spiders, Ashley has set up bird exclusion plots to examine the abundance of insects when bird predation is eliminated vs. control plots under natural conditions. To eliminate bird predation, she places a PVC pipe frame covered in bird netting over sections of tundra.

Birds

PhD students Jesse Krause, and Jonathan Perez from the University of California Davis were especially patient with the rain in hopes of being able to capture a bird while I was out with the group. They use mist nets to capture the birds, but much like the squirrels from my July 10 journal it is not good for the birds to be exposed to the elements in a trap on a cold, wet day. We finally caught a break in the rain after lunch in the field and quickly brought out the mist nets. Mist nets look like very fine-stringed volleyball nets. They stretch between two poles from just a foot of the ground to a height of roughly 6 feet.

Jesse Krause, and research assistant/naturalist Jake Schas setting up a mist net.

Jesse Krause, and research assistant/naturalist Jake Schas setting up a mist net.

Once the net is set up Jesse plays repeated calls of White-crowned Sparrows on an iPod connected to a small speaker, places the iPod into a baggie to protect it from rain, and sets it on the ground near the mist net. Now we wait for curious birds to fly into the net. The group is unhappy with the location of the net and decides to move it after about 15 minutes of no luck. Bird activity seemed low on this cold, wet day. Ten more minutes pass, then Jesse yells "we got one" and runs to the net. He returns seconds later with a small fluffy bird in his hand. The group quickly gets to work by first drawing some blood samples. They then proceed through a series of measurements and banding the bird with a unique identification tag.

A juvenile White-crowned Sparrow.

A juvenile White-crowned Sparrow.

Taking blood samples.

Taking blood samples.

Banding the leg for identification and tracking.

Banding the leg for identification and tracking.

Measuring tarsus length.

Measuring tarsus length.

Measuring beak length.

Measuring beak length.

Assessing body condition. Birds don't have pigment in their skin, so you can view muscle and fat to assess body condition.

Assessing body condition. Birds don't have pigment in their skin, so you can view muscle and fat to assess body condition.

Measuring wing length.

Measuring wing length.

After recording several observations, Jesse showed me how to properly hold the bird. The bird was incredibly soft, light and delicate! My jacket was already so muddy that the excrement the bird dropped on it quickly blended in.

Nick LaFave holding a White-crowned Sparrow.

Nick LaFave holding a White-crowned Sparrow.

Fresh bird droppings running down my jacket.

Fresh bird droppings running down my jacket.

Jesse places the bird in a bag to hang from a bush. Approximately 30 minutes from the time of capture the group takes another blood sample and weighs the bird. They analyze the blood samples for changes in hormone levels in response to being exposed to 30 minutes of stress. As the arctic warms, we see a pattern of some birds expanding their geographic ranges north due to habitat moving to higher latitudes. This group is especially interested in comparing stress response in birds that are on the edge of their geographic range and comparing it to birds that are still located within the traditional range for the species. This is just one of many ways that the group looks at the interactions between changes in tundra vegetation and the birds that live here. After a few final measurements, Jesse looks at me and says, "You know you want to," as he hands the bird back to me. I take one last minute to enjoy this rare opportunity before placing the bird in my outstretched palm where he quickly flies away to the safety of a nearby shrub.

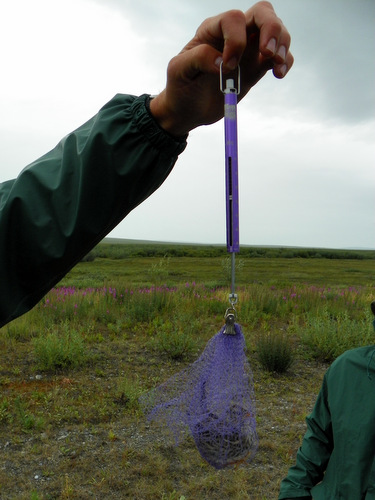

Bird hanging out in a stress bag.

Bird hanging out in a stress bag.

Weighing a bird.

Weighing a bird.

This was some very cool science!