Glaciers 101

I am down here as a participant in the Thwaites Offshore Research, or THOR, project. THOR scientists are investigating drivers of glacier, ocean, and climate change using information recorded in sediments deposited on the seafloor by the Thwaites Glacier over the last several thousand years and especially the past few decades. What can the sea floor tell us about the movement and melting of the ice above it? Lots - but in order to make sense of that, we need to understand some of the basics of glaciers themselves. (Side bar: To all the Science Olympiad students out there - next time the Dynamic Planet focuses on glaciers, hit me up. I'm a total expert now. Sorry, Kaylee, that I developed this expertise too late to be a helpful coach when you were studying last year).

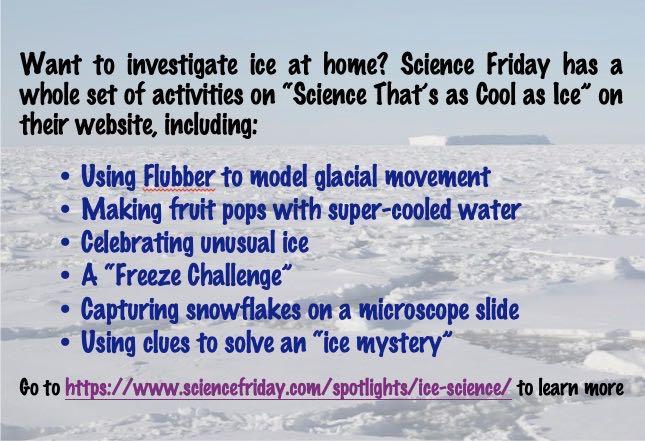

There are numerous activities related to glaciers and ice on the Science Friday "Science That's as Cool as Ice" website.

There are numerous activities related to glaciers and ice on the Science Friday "Science That's as Cool as Ice" website.

What is a glacier?

According to the 2017 version of Wikipedia, "a glacier is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight." Glaciers are not only constantly moving, they are also constantly changing, getting bigger as snow is added to one side (called the accumulation zone) and shrinking as they melt and break at the other end (called the ablation zone). The more a glacier builds up, the more compressed or squeezed together the ice at its base becomes. You might have noticed the light bluish color on many of the icebergs I have photographed - icebergs are pieces of broken glacier, and the blue color is indicative of ice that has been squeezed so much that it doesn't have any air bubbles in it - air bubbles make ice look white. Icebergs also often look white because they are covered with fresh snow.

Blue ice has been compacted over time and no longer contains any air bubbles. On Edwards Island #10 in the Amundsen Sea off the southwest coast of Antarctica.

Blue ice has been compacted over time and no longer contains any air bubbles. On Edwards Island #10 in the Amundsen Sea off the southwest coast of Antarctica.

Glacial bodies larger than 19,000 square miles are called ice sheets and currently, they only exist in two places: Greenland in the northern hemisphere and Antarctica in the south - 99% of Earth's glacial ice is found in these two places (there are also mountain glaciers - those snow caps in places like the Alps or the Rocky Mountains - that have many of the same properties as ice sheets, but on a much smaller scale).

The edges of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet are divided glaciers like Thwaites. Thwaites terminates in an ice shelf that juts out into and floats on the ocean. When ice shelves break apart (as happened earlier this week at the nearby Pine Island Glacier), it does not immediately contribute to sea level rise because the ice shelf was already floating in the water. But the deterioration of the ice shelf means that more ice from the glacier can flow in to take its place, thereby increasing the rate at which ice is moved from the land to the sea. The point where the ice of a glacier leaves the land and begins to float is the grounding line, and it is one of the most important features to scientists studying how glaciers melt. If anyone tried the little experiment I described in an earlier post, I hope that you noticed that ice in the water melts faster than ice in the same temperature air. Keep that grounding line in mind - that place where glacier meets ocean - because it is a key feature of the story of Thwaites, and one I'll come back to again.

Comments

Add new comment