The Story of a Core

A main goal of the Thwaites Offshore Research team is to investigate drivers of ice sheet, ocean and climate change recorded in sediments deposited in the Amundsen Sea near Thwaites Glacier over the last several thousand years and especially the last decades. One of the chief strategies for achieving this goal is to take core samples - lots and lots of core samples. A core sample is collected by pushing a hollow cylinder into the substance you want to investigate - sometimes it is rock, or ice, or a person’s bones, or soil, or the surface of Mars, or the trunk of a tree, or in our case the sediments that build up on the seafloor. When the coring device is retrieved, the column of sample collected contains vast amounts of information for the scientists that know how to decipher it. I’ve seen cores described as history books, with each layer containing a new page of information and the deeper you go beneath the surface, the further back in time you can explore.

A section of ice core with a temperature probe taken from the sea ice of the Ross Sea, Antarctica. Photo by Jennifer Bault (PolarTREC 2017), courtesy of ARCUS.

A section of ice core with a temperature probe taken from the sea ice of the Ross Sea, Antarctica. Photo by Jennifer Bault (PolarTREC 2017), courtesy of ARCUS.

Some ice cores collected in East Antarctica provide a record dating back over 800,000 years. From NASA’s Introduction to Ice Cores: How do we know they’re that old? Each season’s snowfall has slightly different properties than the last. These differences create annual layers in the ice that can be used to count the age of the ice, just like rings inside a tree. However, the more the ice compacts and the less that snow accumulates, the harder it is to see these annual layers. To analyze the age of the deepest layers, scientists use a variety of methods, including measurements of the chemical composition and electrical conductivity of the ice. Scientists also use computer-modeling techniques that can help to understand the relationship between the depth of the core and the age of the ice. The time frame of history revealed by our cores varies greatly - both with the depth of the core collected and with the specific location on the sea floor. There are some spots that have thousands of years of sediment and others that were recently scraped down to the bedrock by a massive iceberg dragging across their surface. We use a system called Knudsen sonar to evaluate the depth and layering of sediments present before choosing a location to core.

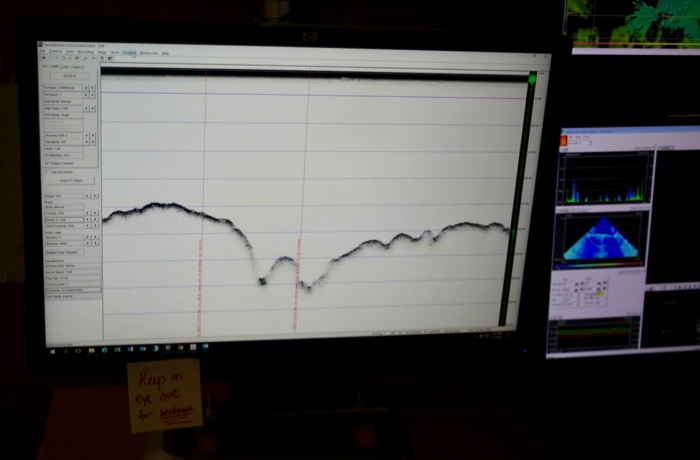

The Knudsen sonar collects information on water depth and on the presence of sediment layers on the seafloor in the Amundsen Sea, Antarctica.

The Knudsen sonar collects information on water depth and on the presence of sediment layers on the seafloor in the Amundsen Sea, Antarctica.

Sediment is then sampled and analyzed in what seems like a million different ways (but is realistically closer to twenty) in order to create a comprehensive picture of what the water and ice looked like over the course of the past one hundred or one thousand or ten thousand years. Dr. Ali Graham used an analogy to describe why using multiple tests makes all the data more meaningful. "Think of trying to recognize a person by revealing only one feature of their face. You probably couldn't do it. Same with our core data - it’s like this test shows you the shape of the eyebrows and the next test reveals the upper lip or a cheekbone or a nostril and you have to combine the data from many tests in order to know what someone looked like, and then you're like, Hey, that's Tom Cruise.” It will take a lot of data in order to draw all the features we need to understand Thwaites Glacier. Researchers will search for evidence of the position of the glacier, the speed at which it moved across the seafloor, what it carried in its ice, the rate it melted, and past changes in water salinity and temperature that will be linked to the location of the Circumpolar Deep Water.

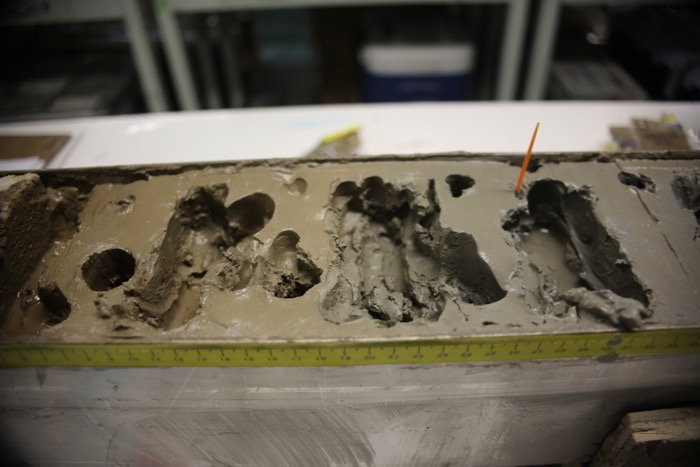

Sediment cores are sampled for forams, trace metals, grain size, shear strength, carbon and nitrogen levels, and other properties. In the aft dry lab of the R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer icebreaker, Amundsen Sea, Antarctica.

Sediment cores are sampled for forams, trace metals, grain size, shear strength, carbon and nitrogen levels, and other properties. In the aft dry lab of the R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer icebreaker, Amundsen Sea, Antarctica.

Try This at Home:

What could you do to create a model of an ice core at home? Think about what materials you could use and how long it would take to produce. Do you think having students analyze a homemade ice core would be a useful project for the classroom? Why or why not?

The Earth Exploration Toolkit has a chapter dedicated to exploring the interpretation of sediment cores to reveal information about climate change. For younger students, BrainPop has a lesson on soil layers and cores.

Comments

Add new comment